Bhupen Hazarika sang in a baritone voice that paradoxically had nasal touch all the same, while Kunnakudi Vaidyanathan played the violin with a constant yearning to foray up to the upper octaves and beyond.

Also, the Carnatic instrumentalist set his concerts to a tone that was largely shrill and busy, while the Assamese musician had much of his renditions wafting in a relaxed pace though with a lilt typical of the country’s Northeast.

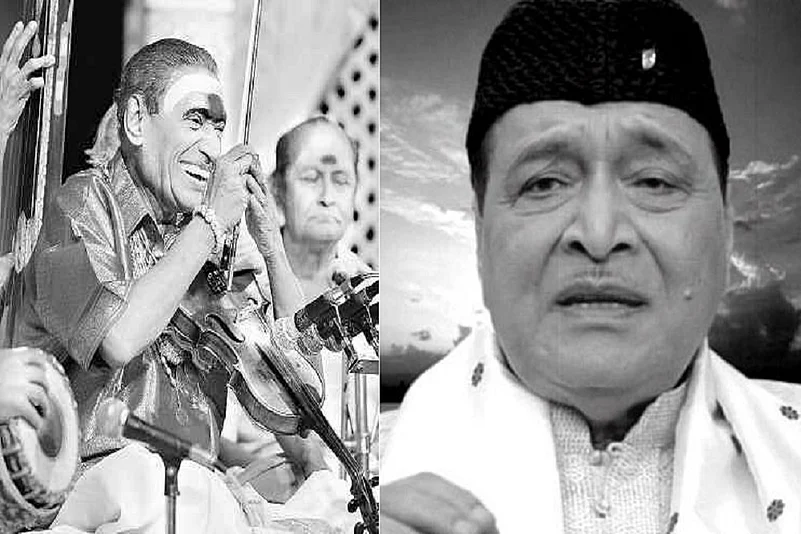

If today is Hazarika’s 92nd birth anniversary, this September 8 also marks the ninth year of the death of Vaidyanathan. That is mere coincidence, yet the lifetime contributions of the two Padma awardees to the world of Indian music will be a fascinating exploration with their set of similarities and contrasts.

Hazarika (1926-2011) owned a raspy timbre that was thick as well as flexible, much to the

fascination of music buffs from any part of his motherland. Graininess is a typical feature in the lower regions of the male throat, yet the effect was particularly soothing when it emerged out of the lyricist-vocalist who hailed from the grassy plains of Sadiya surrounded by Himalayan forests.

Hazarika didn’t confine his musical path to just one stream. That way, somewhat like

Kunnakudi, he straddled an array of genres—and ventured into fields even beyond the world of music. Films had been a constant fascination of both Bhupen and Vaidyanathan, with the former going as far as to direct no less than 14 movies.

Hazarika also produced a film three decades ago from now. Ek Pal (1986) was Hindi movie

directed by Kalpana Lajmi, starring Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah and Farooq Shaikh

besides Shreeram Lagoo and Dina Pathak. Bhupen not only acted in the 135-minute flick, he

was also the composer of its songs written by Gulzar. He did sing too in Ek Pal. The number

was based on Bihu, the springtime songs that celebrate love amid the beauty of nature

around.

Down south of the peninsula, the 1935-born Kunnakudi, equally a showman, also did produce a movie—that was in Tamil. Thodi Ragam was a 1983 family film that had an acclaimed Carnatic vocalist cast as the protagonist vis-à- vis a popular actress. Madurai T.N. Seshagopalan acted as the hero opposite Nalini Ramarajan, but it bombed. Directed by Kunnadi’s son-in- law V. Ramakrishnan, the work saw the maverick violinist take charge of the music department. The ditty, Thodiyil Pada Vanthen—a critic notes—has “numerous flowery sangatis and indulges the adventurous trait in the composer, singer and listener”. Equally or more popular was another song, starting with the line Kottampatti roatile:

Kunnakudi made guest appearances in a few Tamil films. In fact, three years before his death,

the violinist showed his face briefly in a Tamil film. Anniyan, a 2005 psychological thriller, had

him busy in the midst of the famed Thyagaraja Aradhana on the Cauvery banks at the classical

composer’s birthplace in present-day Thanjavur district. Kunnakudi, for long, was the chief

organiser of the prestigious annual Carnatic music festival at Thiruvaiyaru, having also been the impresario of its highlight: the Pancharatna kritis, or the forenoon presentation of five jewel-like shining compositions of Thyagaraja (1767-1847) by musicians in several rows.

Kunnakudi, who had accompanied on the violin Carnatic stalwart Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar at the age of 12 and later-year titans like Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer and Maharajapuram Santhanam on the concert platform, went on to branch out as a solo performer with a big entourage. Simultaneously, he made it big in the world of devotional music, what with composing over 700 songs, much of which HMV marketed.

At the kacheri stages, Kunnakudi had the second half of his three-hour recitals slotted for non-classical items. That largely included devotional, folk and film songs. As much as introducing the works of the Carnatic trinity and other vintage classical composers to non-aficionados, he believed in regaling them with light and racy items. A breathless song that popular singer S.P. Balasubramanian sang (and acted) in Keladi Kanmani (1990) was, for instance, one that Kunnakudi sought to reproduce on the violin at Carnatic stages—after a brief introduction peppered with facial histrionics.

If Kunnakudi looked religious with his ash-smeared forehead sporting a big roundish kumkum

spot, Hazarika was rarely seen letting out his religiosity, if any. (Quite a few in the Deccan would have mistaken the cap-bearing face for a Muslim’s.) Bhupen was much restrained in his

conduct, seldom flamboyant even with his music. The bewitching nature of his much-hailed

strains owe basically to the richness of the folk songs of his verdant region with its undulations.

Somewhat simplistically put, Hazarika drew his musical energy from Assamese culture and

spread it to other parts of the world, when Kunnakudi brought in entertainment from non-

Carnatic streams of music and presented it before audiences gathered at his classical concerts.