Once upon a time, going to cinemas approximated a religious experience. Like devotees seeking darshan, cinephiles left their homes, reached the theatres, and hoped to get tickets. The ritual involved anticipation, thrills, and questions: What if the balcony rows are full? What if the entire show is sold out? What if the ‘black tickets’ are exorbitant? They all meant one thing: a lack of control. Because whether you arrived early or late, felt rushed or relaxed, the show would start on time. Like a darshan. And that lack of control persisted during the screening. Found a movie boring? Too bad, can’t skip forward. Felt like taking a break? Too bad, stay put. Want to watch something else? You know where the door is.

But now, if you’ve to book tickets for a theatrical release, you don’t even need to move: a few taps on the phone, an app, a few more taps, and that’s it. With the explosion of multiplexes, you’re almost always guaranteed a seat. Or, even better, now the wells woo the parched: theatres meet you on your phone, laptop, and iPad, screening films across countries, genres, and decades. If a movie is too slow, you tap “+10”; you can skip subplots, replay scenes, pause and play in chunks—across days, even months—or switch to something else that lulls you to sleep. It’s all too easy, all too convenient: digital has replaced darshan.

That world, symbolised by single screens, now exists in fleeting fragments, like teetotallers among drunks, people among ghosts. Sometimes you’ll have to peer hard to spot, because many talkies have stopped talking. Outside a locked gate of Imperial Cinema in Mumbai, a street hawker sells electronics, shoes, and bags. Ranikhet’s Globe Theatre resembles a forlorn bungalow hijacked by rampant vegetation. Mumbai’s century-old Central Plaza, which shut in 2020, still displays its name in big silver letters—just the “T” is missing. Quite apt: the single screens haven’t been ‘central’ to our lives in a long time. In the last two decades, around 12,000 of them have shut, dwindling to less than 7,000. In Mumbai, they’ve reduced from 200 to 15; in Delhi, from 80 to 3.

Those theatres, however, didn’t just show movies, they were theatrical themselves, reeling off stories about the country’s history, heritage, and architecture. Some, managing to survive the onslaught of time, shine as architectural marvels (many in Art Deco style), imbuing our cities and towns, often washed in sameness, with textured signatures: Liberty Cinema, Mumbai; Raj Mandir, Jaipur; Phul Cinema, Patiala. “Audiences had relationships with such places,” says cinematographer Hemant Chaturvedi who, travelling 40,000 kilometres across 850 towns in 17 Indian states in the last few years, has photographed over 1,000 single-screen cinemas. “Many people only watched movies in a certain theatre.” During a show of Mughal-E-Azam in a single-screen in Mumbai, remembers Chaturvedi, “every audience member, irrespective of age or caste or religion, knew every single dialogue. When Madhubala says, ‘Kaaton ko murjhaane ka khauf nahin hota [thorns are not worried about drying]’, and you hear it from the mouths of 1,000 people, it’s just mind-boggling. Now you’ve 200-seaters, kya mazaa aata hai [what enjoyment does that give]? You’re watching a film projected on the size of a dupatta.”

Unlike the multiplexes—which, besides devoid of architectural characters, sell expensive tickets—single-screen theatres welcomed different classes under the same roof. Even if for a few hours, they provided a shared space and feel. Multiplexes, on the other hand, located in malls, have become a “gated experience”, writes Tejaswini Ganti in Producing Bollywood. Their designs and locations exemplify an “aesthetic of intimidation”: “uniformed security guards; English-speaking staff; expansive entrances set at considerable distances from the streets; driveways only open to private cars or cabs; and inaccessibility of public transportation”. They all ensure that the multiplexes’ clientele “are only those” who have the “confidence and the class privilege” to enter such spaces.

“We’ve lost the collective experience of watching films, where your emotions get charged by people around you,” says Chaturvedi. “We’ve lost architecture. We’ve lost cities’ visual identities. And we’ve lost a large section of society who went to the movies.” Cinema, like much else in this country, has been remoulded as a project of the elites, by the elites, for the elites. Even before the multiplexes, or economic liberalisation, the filmmakers had divided the audiences into the ‘masses and the classes’, blaming the latter, especially in the late ’80s, for flocking to inane and violent entertainers (thereby ‘diluting’ cinema’s quality), without looking inwards and trying to understand the reasons of disconnect. Now with the luxury of homogenous cocoons, which exclude more than they include, many makers neither pretend nor care.

Till a decade ago, a large section of rural audience, especially in the villages of Maharashtra, watched films on “tambu cinema” or travelling talkies. Like awaited festivals, they came once a year—during religious fairs called jatra. An owner of a travelling cinema parked his conical tent in a field. A film projector, in a truck decked with movie posters, beamed the flickering images on a white cloth. Hundreds of villagers, sitting on the ground, watched the magic unfold, sometimes slipping into stunned silence, sometimes erupting into whistles and claps and dance. Sometimes close to a dozen tents sprawled on the same field, showing different films, resembling a ‘rural multiplex’. This spectacle rubbed shoulders with other spectacles: circuses, magicians, folk dancers. This was as collective, or as democratic, an experience as it could be: tickets came for cheap (around Rs 15 in 2008) and a movie was changed—or replayed—if the audiences found it boring or riveting.

“They existed as a form of shared ritual,” says Shirley Abraham, the co-director of the Cannes-prize winning documentary The Travelling Cinemas (2016). “We saw people soaking the magic of movies in a very palpable and tactile way.” When such exhibitions came to the villages in the 1940s, she adds, women couldn’t access live entertainments in fairs, as they were considered “raunchy” and the “preserve of men”. That changed with time, though, with many leaving their homes to watch mythologicals. “Women told us that they came to the cinemas to cry. Because they didn’t have that kind of space at home.”

With their reels and trucks and tents, the travelling showmen went far and wide, screening movies at “fairs, markets, graveyards”. And they found no shortage of bhakts. “It felt like the kind of devotion you preserve for religious rituals,” says Abraham. “In the early years of the travelling cinemas, audiences removed their chappals before entering the tents. Because for them, it really felt like entering a temple.”

But over the last decade—as TVs and DVDs and smartphones supplied accessible and round-the-clock entertainment—such cinemas have become less of a reality and more of a memory. At one point, Maharashtra alone had over 1,000 travelling talkies; now just a few dozen remain. Some of their owners have transitioned from film to digital projection; many, however, continue to struggle and gravitate to other occupations, such as selling vegetables. “That whole world,” says Abraham, “was like a real nasha.” Besides providing entertainment and sustaining livelihoods, it “preserved a way of life”. There was “something so fundamental and pure and primal”, she says, about that “living and breathing system of cinema”.

Numerous professionals once employed in single screens or travelling talkies didn’t just lose their livelihoods but also their language of life. Imagine waking up to a world that has outlived your ‘utility’. “When I worked on film reels, I sometimes made mistakes,” a projectionist in Nagpur, who had recently switched to digital, told Chaturvedi. “Sometimes the alignment would be off, sometimes a reel got cut. And people would lose it—they’d give maa-behen ki gaalis [sexist slurs]. But now, they’ve forgotten that there’s a person sitting upstairs. Now I yearn for those abuses—curse me, tell me I matter.”

Such seismic shifts, pervading the making of movies, have spawned a raging debate over the last decade. A debate swinging from one ideology to the other. A debate split among evangelists, fanatics, pragmatists. A debate comprising so many arguments and counter-arguments—that it has pros of cons, cons of pros, naysayers, champions, trailblazers, traditionalists, rationalists, romantics—that it makes your head spin. Celluloid versus digital.

For the first 100 years of cinema, movies were shot on a film stock, before digital cameras exploded on the scene and the tech evolved so much that in 2012 more Hollywood films were made on digital than celluloid—a number tilting so much in the former’s favour that celluloid seems like a relic of the past. And with the dominance of OTT platforms, digital has become so ubiquitous—its advantages recounted to us so many times—that we’ve almost forgotten that it is just another medium. “When people ask me why do you still shoot on celluloid,” said Christopher Nolan in the documentary Side by Side (2012), “I wonder why isn’t this asked more: Why do you still shoot on digital?”

If celluloid is chemistry (or alchemy), then digital is electronics (or lines). A film camera requires a new magazine to be loaded around every 10 minutes; digital doesn’t, allowing for much longer takes. Since film stocks are expensive, every shot bleeds money. But digital, with reusable memory cards, imposes no such stress. While shooting on film, directors have to wait for the dailies the next day (as the reels need to be processed in a lab); digital produces instantaneous footage. Digital cameras are also nimble and quiet—unlike celluloid, which emits a whirring sound—enabling cinematographers to slink in crowded areas and, even, shoot surreptitiously. And since digital doesn’t have rolling costs, such as buying newer film stocks and processing them, it comes much cheaper in the long run, democratising the filmmaking medium.

We’ve heard these points many times before. These comparisons, though, don’t just lie in the realm of cinema alone in 2023. Charged with metaphorical and philosophical meanings, they can be applied to our larger lifestyles (controlled by countless apps, ranging from social media to food delivery to streaming platforms). Because most arguments in favour of the new tech these days, even beyond cinema, can be summarised like the following: that digital, trumping analog, enables a world that’s much cheaper and more convenient, providing many options.

But ... does it?

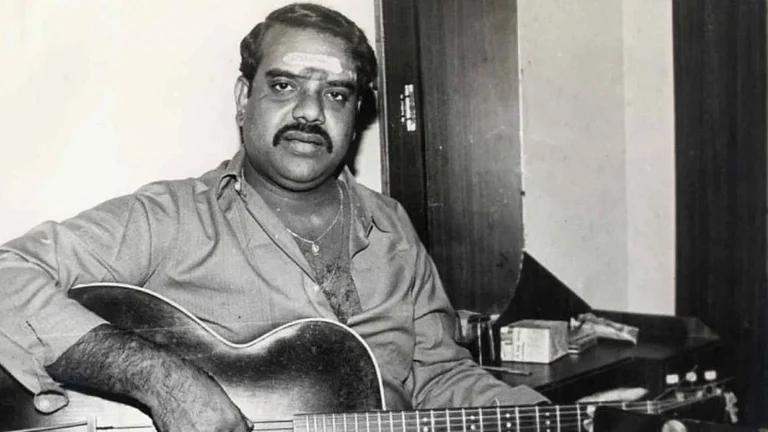

“It’s a complete myth, at a feature film level, that digital is cheaper than celluloid,” says Chaturvedi. A cinematographer for over a decade, who has shot such dramas as Company (2002), Maqbool (2003), and Ishaqzaade (2013), he quit Bollywood in 2015 to focus on his personal projects. “In my last film [Brothers (2015)], I threw a hissy fit in the office of Dharma Productions, when they insisted on digital.” When they said “it’d be too costly”, he gave them an offer they couldn’t refuse: “Boss, if this costs more than digital, then you deduct it from my salary.” He shot on “expired Fuji film” using a “two-to-three-year-old stock”, making it “the last movie to be shot on celluloid in India”. What about the final cost? “22 per cent cheaper”.

His abiding frustration as a cinematographer while working on digital came from this pervasive belief that, “How does it matter that the camera is running? It’s not as if it costs anything.” While shooting on celluloid, he and the directors used to “design takes”—“a long shot for this part of the scene”, then a “close-up or a tracking” shot. They would “not shoot the entire sequence” together but “the start of a scene, the middle, and the end” with some coverage in between. “But when digital came, the directors started filming every shot as a master [covering all the actors in the frame from the start to the end of the scene] on every lens from every angle.” It drained him out.

“Naseeruddin Shah once told me,” says Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, the founder of Film Heritage Foundation, a non-profit supporting the conservation, preservation, and restoration of films, “‘On digital shoots, they switch on the camera and who knows what they capture when, and you’re expected to keep performing. One take after the other, we are rolling, we are rolling, we are rolling. In celluloid, I knew that after 10 minutes of stock, I could hear the sound and it’s gonna end. Then I get a breather and I can rethink and give another take.’”

A huge proponent and exponent of digital filmmaking, David Fincher says he likes the flexibility that the medium provides, allowing him and his crew to watch the footage on set. “[But] if you’re watching a monitor on set and you feel that you’re really seeing what you’ve got, then you’re fooling yourself,” says Nolan in the documentary Side by Side. “The audience is gonna watch that film on a screen, that is, a thousand times bigger than that.” The magic of celluloid, adds Dungarpur, arose from the “wait for the experience of seeing your rushes. Because art is, finally, a spontaneous creation. It’s not so controlled. When you control everything, you overdo it.” He quotes Ghalib: Aate Hain Ghaib Se Ye Mazameen Khayal Mein—“I don’t know where my thoughts come from, but they come from Above”. Cinema was like that, he adds, “it’s almost a religious thing. Which reminds me, so many great artists and painters have emerged from religious institutions.”

“Celluloid’s image quality is also almost what your eye sees it—what you experience in real life,” he says. “But the image captured by digital is absolutely different; it gives you an enhanced quality of a different essence.” Given that celluloid comprises “grains, chemical, and silver”, it gives “depth, resolution, and texture” to visuals. “Celluloid gives you a resolution of 24K. When we go to a theatre, or watch TV, we only experience 4K.”

But in today’s world, where it’s not practical or possible to shun digital, the main question shouldn’t be ‘celluloid or digital’ but ‘celluloid and digital’. Consider Sean Baker, a brilliant American filmmaker. He shot his second feature, Tangerine (2015), a drama about trans sex workers in LA, on … iPhone. A largely financial decision, as movies on transgender characters are tough to sell in Hollywood. But digital also complemented its frenetic, chaotic world that often erupted in disquieting binaries. He shot his next, The Florida Project (2017), an endearing drama about a six-year-old girl living with her unemployed mother in a budget motel, on celluloid. Again, for a piece with a life-like rhythm where time seems to have stalled, celluloid made perfect sense. So, the message could dictate the medium. “Sean is a true artist,” says Dungarpur. “He’s like a painter who chooses his canvas, which is fantastic. Not a painter who has been thrusted with limited options. But we’ve entered an era where we’re told that the only way to make—and show—films is through digital.”

A ‘lack of choice’ in a world inundated with choices. Or, well, we’ve so much now that we’re left with so little. “Control and distortion are the two key words in digital,” says Dungarpur. It’s something that informs the film-consumption culture as well. We’ve so many OTT platforms now that cinema, which once brought people together, has become another tool to snap our societal bonds, reducing us to pixelated islands. “In the age of big theatres, the experience controlled us,” says Chaturvedi. “Now, we want to control the experience.” The true devotees no longer exist; they’ve all become Gods.

(This appeared in the print as 'A Subliminal Loss')