At a festival in Scotland’s Edinburgh in 1965, world-renowned musician Yehudi Menuhin gifted Indian instrumentalist Lalgudi Jayaraman with an Italian violin. For, the Carnatic exponent’s finesse in playing the fiddle and mastery in unveiling varied Oriental melody-types had thoroughly impressed the American-born conductor, who would keep asking Lalgudi to play classical ragas from the peninsular part of his Asian country.

The story didn’t end there. In a beautiful sequel that happened not many years thence, New York-born violinist Menuhin visited India, where Lalgudi presented him an idol so representative of Hindustan’s heritage: a Nataraja statue. That is, an ivory-made idol of Shiva in a striking posture. Of a particularly elegant moment from the mythological lord’s famed cosmic dance.

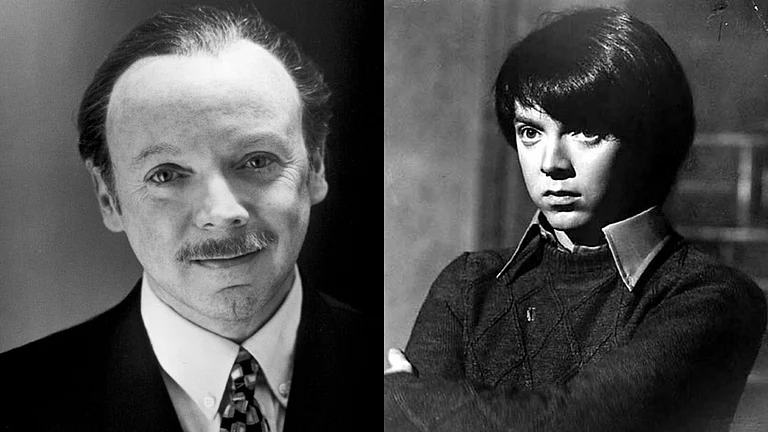

Last week marked the fifth death anniversary of Lalgudi, which is actually the name of a small town along the Cauvery belt (in present-day Tamil Nadu’s Tiruchirapalli district) where Jarayaman was born in 1930. That means the Carnatic violinist was 35 when that autograph moment happened in Britain. (For Menuhin, a Jew who spent most of his life in the United Kingdom, 1965, incidentally, was the 20th anniversary of his concerts [this time on the piano] for the survivors of Nazi concentration camps in a series primarily for the benefit of allied soldiers during World War II.)

Today is World Dance Day, a week after the date of Lalgudi’s death: April 22. Besides being a performer-scholar, this violinist (died in 2013) had a bouquet of Carnatic compositions to his credit. Among them is a genre called ‘Pada Varnam’, whose lines largely deal with the heroine’s (often wistful) love for her man and thus lends itself to shringara-centric expressions in Bharatanatyam, the classical dance of the Deccan. They are typically rich in literary content (unlike the thoroughly-structured ‘Tana Varnam’ in Carnatic), thus providing more scope for thematic interpretations. All the same, the ‘Pada Varnam’ facilitates rich showcase of varied-speed adavu and nadai (steps are gaits) typical of the south Indian dance.

Lalgudi’s proven expertise in Pada Varnams perhaps explains the reason for his gifting a Nataraja statue to Menuhin, 14 years older. Among the compositions of that category is one in Charukesi ragam. This is one which the revered Carnatic violinist took up as an assignment, accepting a request from top danseuse Chitra Visweswaran, a fellow Chennaiite.

The Bharatanatyam exponent, now 68, used to perform this Pada Varnam, initially with vocal support by her musician husband R. Visweswaran (1944-2007). “I am partial to the Charukesi varnam especially because it suited my husband’s voice so well,” she is said to have told a national newspaper on the occasion of Lalgudi’s 80th birthday in September 2010. The report also makes clear Chitra’s admiration for “Lalgudi Mama”, who had also composed another varnam for her to dance. That was in ragam Shanmukhapriya, where she wanted the song to be based on bhakti rasa (the emotion of devotion for god).

“Similarly, the navaragamalika varnam on the nine forms of Devi, Angayarkanni’ (and set to as many ragas), is a magnum opus, rich in content and music,” adds the Padma awardee trained under Tiruvudaimarudur-native devadasi T.A. Rajalakshmi who had settled in Calcutta, where Chitra also learned Manipuri and Kathak. “His compositions blend melody with meaning in a sensitive manner and that makes it easy to translate them into another genre; they spurt the dancer’s creativity.

The write-up, which is a compilation in The Hindu, also features frontline dancers Sudharani Raghupathy praising Lalgudi’s Neelambari-ragam pada varnam (Senthil mevum deva deva) and Priyadarshini Govind selecting a Tilang tillana of the violinist as one of her all-time favourites. Separately, young Carnatic vocalist Vidya Subramanian, a Lalgudi disciple, notes that his Devi-lauding varnam in Devagandhari raga successfully uses certain musical techniques to link various swaras and create an awe-inspiring effect. “In the popular Valaji varnam, he has varied the eduppu (starting point) of lines to create an element of surprise in the flow of the composition,” adds the musician (who learned under Lalgudi since 1993) in a cultural portal.

As for focusing the Charukesi piece on International Dance Day (on since 1982, in memory of French balletmaster Jean-Georges Noverre [1727-1810]), ‘Innam en manam’ is arguably the most celebrated of the Lalgudi varnams, having proven to be highly impressive both on Carnatic and Bharatanatyam stages. Starting with ‘Innam en manam ariyadavar pola, Irundidal nyayama yadava madhava’, the meaning of the first two lines of the Tamil composition goes thus: Is it just to behave as if you do not know my mind, hey Krishna? The lyricism continues unabated: Is all this drama something you rehearsed before, O King, O lotus-eyed, coloured like a gem? O beautiful lord, won’t you alleviate my grievances?

In June 2013, on the occasion of the release of violinist’s biography aptly titled An Incurable Romantic, U. Srinivas began his Chennai concert with ‘Innam en manam’. The mandolin wizard couldn’t but go for a verbal appreciation of the piece by Lalgudi—of whom “I am the greatest fan”. The varnam has been structured in such a way that each of its phrases brims with the beauty of Charukesi, he said.

What Srinivas (1969-2014) tacitly meant, most likely, was that the Lalgudi notes keep lilting like every cell of a lissom dancer herself.