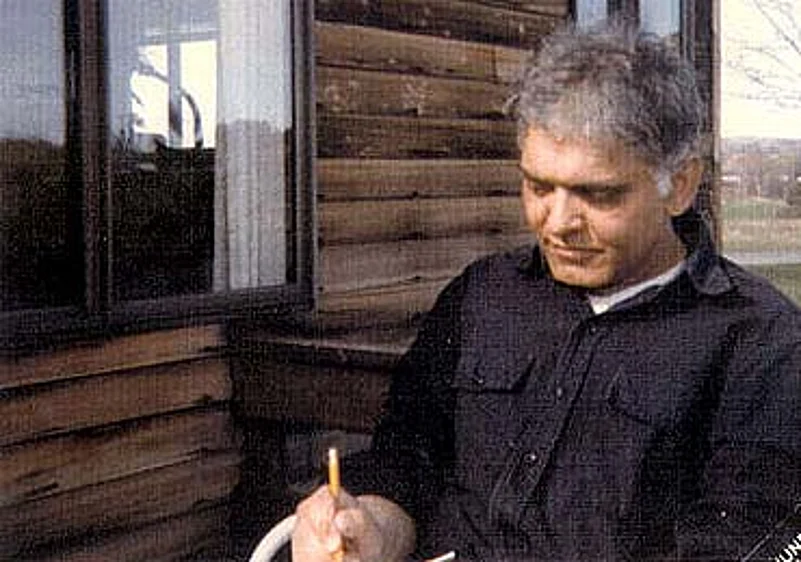

Among anticolonial intellectuals, Pakistani scholar and activist Eqbal Ahmad(1933-99), who toward the end of his life spent fifteen years teaching atHampshire College in Massachusetts, holds a special place. He never published aclassic text of the order of Frantz Fanon's Wretched of the Earth orEdward Said's Orientalism, nor did he achieve anything like fame. (Theclosest he came was a passing notoriety during the Nixon era, when he wasindicted on charges of conspiring to kidnap Henry Kissinger.) Yet everyone whowas someone in the vast but—in the West—obscure world of Third Worldradicalism knew Ahmad, and even his adversaries had a grudging respect for him.As much as Said, he was a mentor to a generation of thinkers, mostly SouthAsian, who have been active in protest struggles in the West as well as on thesubcontinent.

Within a few miles of Ahmad's birthplace in the Indian state of Bihar standsthe mausoleum of Sher Shah Suri, the sixteenth-century ruler who built the GrandTrunk Road across the giant spread of the subcontinent. In a BBC documentarycalled Stories My Country Told Me, Ahmad, traveling in a car across thatgreat unifying marker in the region, cites Sher Shah's remark that "roadsare the carriers of civilization." Ahmad's work as a writer and activistmight be said to have performed the same function. It is not only the power butalso the wide range of his sympathies that astonish. He was a committed engineerof emancipation, building imaginative roads, linking issues across continents.

Though best known for his eloquent speeches and lectures, Ahmad publishedwith some regularity; his Selected Writings, edited by CarolleeBengelsdorf, Margaret Cerullo and Yogesh Chandrani, are now available fromColumbia University Press. They shed light on guerrilla warfare, the cold war,the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, the nuclear tests carried out by India andPakistan. There are more than fifty pieces: Some were written as op-eds; a few were delivered as speeches; and severalwere published as scholarly essays.

Yet this collection, for all its riches, offers the merest hint of the scopeof Ahmad's life. He may have taught at a small New England college, but heinhabited a large stage, and his adventures reflected a profoundly committedcosmopolitanism that has since degenerated into a more fashionable, andconsiderably less dangerous, seminar-talk in cultural studies courses onAmerican campuses. During the early 1960s, while he was a doctoral student atPrinceton and doing research in Tunisia, Ahmad rallied to the cause of Algerianindependence and befriended a number of high-ranking FLN leaders exiled inTunis. Upon his return to the United States in the mid-'60s, he became an earlyand impassioned opponent of the war in Vietnam and then, following the 1967Arab-Israeli war, an outspoken advocate for Palestinian rights at a time whensuch a position was virtually taboo in the United States.

Ahmad remained throughout his life a Marxist, but of a special kind, as theIndian social theorist Ashis Nandy reminded me in a recent conversation. Sittingin his home in Delhi, close to the shrine of the fourteenth-century Sufi saintNizamuddin Auliya, Nandy described Ahmad as a Leninist who was long"straining at the leash." Even in the First World, where Ahmad spentmany years, "the most creative Marxists had shed the shackles ofLeninism." And Ahmad did the same with age. But what gave his thinking itssuppleness, Nandy suggested to me, was that Ahmad had been born in a societywhere faith was deeply entrenched and secure. Ideology is not so powerful insuch places. For some members of the radical left, particularly in the West,people in developing countries are an ideological abstraction, on whom fantasiesof liberation are projected from a comfortable distance. These fantasies are notinfrequently laced with condescension. Ahmad, by contrast, was led intopolitical activism by a genuine love and compassion for the peoples of the ThirdWorld, who were anything but strangers to him. "To identify him with anideology, as if he were a fully formed Western man," Nandy told me,"is to do him an injustice. He fought for causes in the Third World and hada robust, life-affirming attitude towards the people among whom he fought."

Not that anyone would have predicted a career of radical, globe-trottingactivism for Ahmad, who was born to a prosperous family of Muslim landowners.But the struggles in British-occupied India, followed by the bloody partitionthat accompanied independence, changed all that. Ahmad, barely a teenager at thetime, was forced to join the long caravan of refugees trekking to Pakistan. Hisfather had earlier been murdered over a property dispute; his mother refused toleave India for Pakistan, reportedly rebuking her sons for having become"Muslim Zionists." In the course of the long march to the newlycreated border, young Ahmad served as an armed sentry, shooting down marauderswho attacked the caravan. The experience was no doubt scarring.

In a sense, the agony of partition—of bloody interethnic riots, massdisplacement and the slaughter of a million civilians—had an effect on SouthAsian intellectuals not unlike that of the Holocaust on Jewish intellectuals: Itbecame their subliminal reference point, the angle of vision that defined theirpolitics. Ahmad drew very specific lessons from the nationalist bloodletting.Like Rabindranath Tagore, a poet and thinker he admired, Ahmad understood thatIndian anti-imperialist movements needed to avoid the ideology of nationalism.In a series of interviews with David Barsamian, published in 2000, Ahmad said,"We rejected Western imperialism, but in the process we embraced Westernnationalism lock, stock, and barrel." The carnage of the partition wasinevitable. And also, arguably, the present-day fundamentalist revival with itsultranationalist underpinnings.

Today, many writers from the subcontinent—notably the Nobel laureateeconomist Amartya Sen, also an admirer of Tagore—echo Ahmad's assertion that"nationalism is an ideology of difference." In his recent book Identityand Violence, Sen argues against the imposition of singular nationalist orcivilizational affiliations on our robustly plural identities. "The sameperson," he writes, "can, for example, be a British citizen, ofMalaysian origin, with Chinese racial characteristics, a stockbroker, anonvegetarian, an asthmatic, a linguist, a bodybuilder, a poet, an opponent ofabortion, a bird-watcher, an astrologer, and one who believes that God createdDarwin to test the gullible." Like Ahmad, Sen a witnessed, as a child, thebrutality of Hindu-Muslim riots. And for Sen, the way out of belligerent,civilizational partitioning lies in cultivating—even acquiring—a complexsocial identity. This should be true not only of individuals but also ofcultures. No civilization has a monopoly on tolerance; each is capable ofbigotry. In saying this, Sen is contesting the modern myth that Europe, andEurope alone, has been home to democracy and freedom. In Identity andViolence, Sen points to the tolerant regimes ruled by the Indian emperorsAshoka (third century BC) and Akbar (sixteenth century AD). When, in the 1590s,"the Inquisitions were quite extensive in Europe, and heretics were stillbeing burned at the stake," Akbar forbade the forcible imposition of faithand advocated individual choice in matters of religious practice.

It is impossible to read arguments like Sen's without thinking of EqbalAhmad, particularly at a time of resurgent racist mythologizing about thesupposed divide between "East" and "West." This divide,according to Ahmad, was reinforced—or, for that matter, bridged—by politicaland economic interests, not by "cultures." In his speech"Terrorism: Theirs and Ours," a 1998 text that found a new life on theInternet after September 11, Ahmad reflected on the marriage of conveniencebetween the United States and the anti-Soviet Afghan mujahedeen, one that bythen had ended in a bitter divorce with the rise of Al Qaeda. As he recalled:

In 1985, President Ronald Reagan received a group ofbearded men in the White House.... They were very ferocious-looking bearded menwith turbans who looked as though they came from another century. Afterreceiving them, President Reagan spoke to the press. He pointed toward them, I'msure some of you will recall that moment, and said, "These men are themoral equivalent of America's founding fathers." These were the AfghanMujahideen. They were at the time, guns in hand, battling the Evil Empire....Terrorists change. The terrorist of yesterday is the hero of today, and the heroof yesterday becomes the terrorist of today. This is a serious matter in theconstantly changing world of images in which we have to keep our heads straightto know what is terrorism and what is not.

During President Clinton's bombing of Afghanistan and Sudan in 1998, Ahmadwarned: "The United States has sowed in the Middle East and in South Asiavery poisonous seeds. These seeds are growing now. Some have ripened, and othersare ripening. An examination of why they were sown, what has grown, and how theyshould be reaped is needed. Missiles won't solve the problem."

At Hampshire College

To read these passages is to be struck not only by Ahmad's prescience but byhis loathing of fundamentalism, his hatred of imperial hypocrisy, his belief inthe value of history, and his commitment to resolving political problems throughdiplomacy, not war. His writing on the Muslim world in particular was notablefor its critical vigilance and integrity, its resistance to received wisdom. Ina 1984 essay titled "Islam and Politics," Ahmad wrote that the truthof "the Muslim condition" had "slipped beyond the grasp of most'experts.'" In his view, Islam in its exemplary form was a religion of theoppressed. Because its rise was dialectically linked to social revolt, he felt,the "religious force and cultural force of Islam continues to outpace itspolitical capabilities." The structural unity that Islamic societies hadachieved, especially in culture and education, had been disrupted by Westernimperialism. As he put it:

The remarkable continuity which, over centuries of growth and expansion,tragedies and disasters, had distinguished Islamic civilization was interrupted.This change, labeled modernization by social scientists, has been experienced bycontemporary Muslims as a disjointed, disorienting, unwilled reality. Thehistory of Muslim peoples in the last one hundred years has been largely ahistory of groping—between betrayals and losses—toward ways to break thisimpasse, to somehow gain control over their collective lives, and link theirpast to the future.

Islamic fundamentalists, although they had little trouble raising theirvoices, only spoke for a minority; the majority of Muslims, Ahmad believed, hadtheir faces turned to the future even as they remained rooted in the past. As hepointed out, the political heroes of the Muslim world in the twentieth centuryhad been "secular, generally Westernized individuals": Kemal Atatürkin Turkey, Muhammad Ali Jinnah in Pakistan, Sukarno in Indonesia, Gamal AbdelNasser in Egypt, Habib Bourguiba in Tunisia and the nine "historicchiefs" of the Algerian Revolution. Even the PLO, he added, claimed torepresent a "secular and democratic" polity, and "two of itsthree most prominent leaders [Marxist leaders George Habash and Nayef Hawatmeh]are Christian."

Accurate as this analysis was for much of the twentieth century, it seemsincongruous today when much of the region that so concerned Ahmad seethes with apassion that is defiantly unsecular. Muslim anger has, of course, been stoked byAmerica's war in Iraq and by Israel's brutal policies toward Palestine andLebanon. Still, this cannot explain why radical Islam (with its variousbranches, tendencies and strategies) has managed to co-opt the anti-imperialstruggle in the Muslim world—and why, by contrast, the Third World Marxism thatAhmad embodied so brilliantly has been unable to offer existential comfort or asuccessful political program to the masses.

One senses that Ahmad was deeply sensitive to the waning influence of radicalsecular politics in the Muslim world, where Islamists increasingly led theopposition to military regimes that had betrayed the dream of independence fromcolonialism. It may well have been this concern that led him to return, shortlybefore his death in 1999, to Pakistan, where he hoped to build a university thatwould teach the humanities. It was to be called Khaldunia University, after thegreat Arab historian Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), whom UN General Secretary KofiAnnan described as "a globalist long before the age of globalization."(When Annan said that, he was delivering the first Eqbal Ahmad lecture atHampshire College. Annan was no doubt also thinking of Ahmad when he remindedhis audience that Khaldun had "argued that civilizations decline when theylose their capacity to comprehend and absorb change, and that 'the greatest ofscholars err when they ignore the environment in which history unfolds.'")Alas, Khaldunia University was never built; according to The Economist'sobituary of Ahmad, he "died before a rupee was raised for it."

Even if his dream had come to fruition, it is hard to imagine Ahmad running auniversity. He was too much the congenital outsider. Ahmad's independence frominstitutions and political parties allowed him to deliver criticism to thoseleast inclined to listen, and it might have been the reason why he earned thetrust of statesmen and revolutionaries throughout the Third World. A critic ofpower rather than an intellectual seeking power, he turned his weakness into asource of strength.

This past summer, Robin Varghese, a former student of Ahmad's at Hampshire,recounted a story to me that he had heard his teacher tell in class. When Ahmadwas in his 20s, he received a Rotary fellowship to come to the United States forfurther studies. He knew that he wanted to see four things when he left thesubcontinent. Three of those four sites he visited en route to this country. Hewent to the Highgate Cemetery in London to pay homage to Karl Marx; he alsovisited 21B Baker Street, for its well-known literary landmark; and he wanderedthrough the British Museum, where his reaction was "Return the loot!"The fourth place that Ahmad wanted to visit was in the United States, inChicago, and it was the site of the Haymarket riot of 1886. Ahmad wanted to gothere because, as a boy, he had been taken to May Day celebrations in India. Henow wanted to lay flowers at the Haymarket monument to honor the strikingworkers who had marched in the first May Day parade.

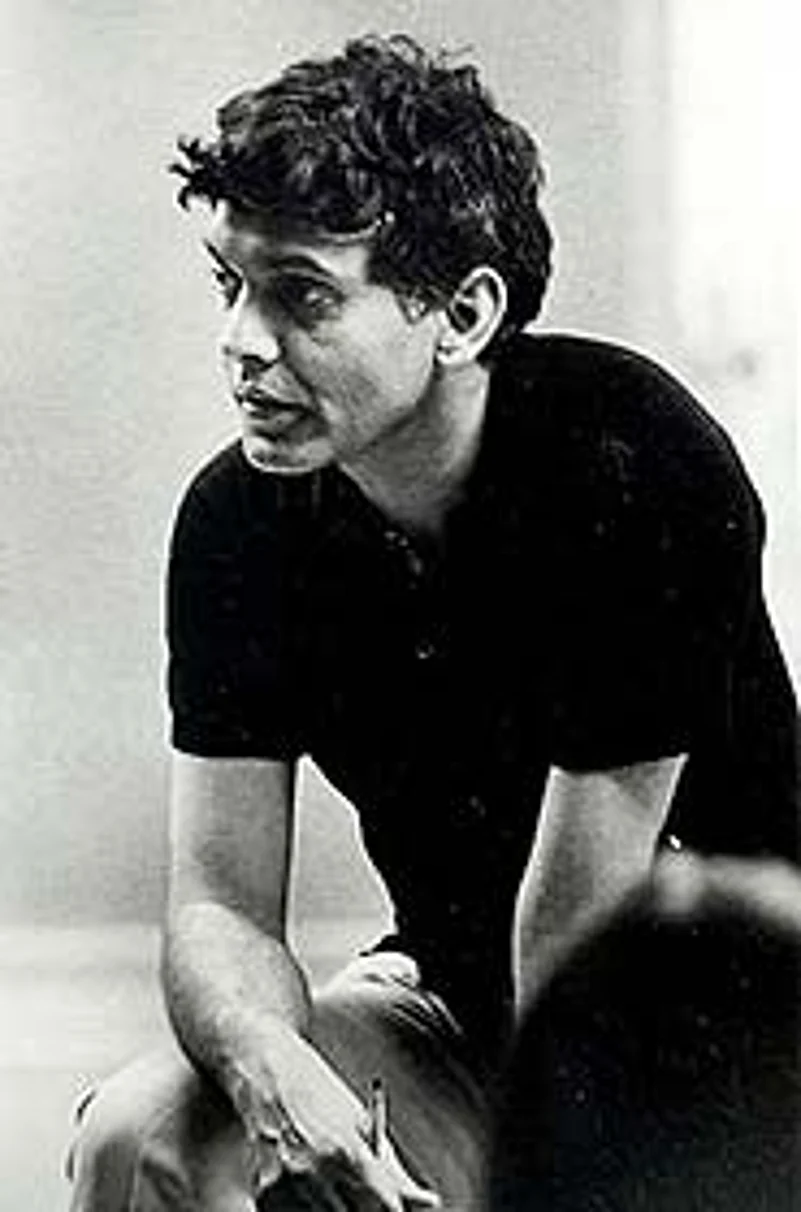

With the Berrigan Brothers at the Kissinger Trial

But several years were to pass before he could visit Chicago. He had arrivedin the United States in 1957 to study history at Occidental College; a yearlater he enrolled at Princeton as a graduate student in political science andMiddle East history. His research then took him to Tunisia, an even furtherdetour from Chicago. It was not until 1967, during his three-year stint as ateacher at Cornell, that Ahmad found himself giving a job talk in the city wherein 1886 laboring men and women had fought to win the eight-hour workday. He lefthis hotel, picked up a bouquet of flowers and, when he arrived at Haymarket,asked where he could find the monument. No one seemed to know of it. Finallysomeone pointed it out to him. It was a statue of a policeman who had preservedlaw and order on that day long ago. Ahmad brought the flowers back with him andgave them to his girlfriend, Julie Diamond, who eventually became his wife.

In 1968, in a speech at an antiwar sit-in, Ahmad, who was now a fellow at theAdlai Stevenson Institute in Chicago, spoke of his search for the Haymarketmonument. He told the audience how shocked he had been that the historicalmemory of workers' resistance, recognized and celebrated throughout the world,had not been honored in its own place of origin. Not long after, two FBI agentsshowed up at Ahmad's door. They wanted to know what he had said about Haymarketand who had been in the audience. It turned out that the Weathermen had justblown up the offending statue of the Chicago policeman.

"I am inclined to tell stories," Eqbal Ahmad had once said, and, inone of his interviews, he offered a vignette about the visit from the two FBIagents:

They first asked me if I was a citizen of the UnitedStates. I said, "No." They said, "Don't you feel that as a guestin this country you should not be going about criticizing the host country'sgovernment?" I said, "I hear your point, but I do want you to knowthat while I am not a citizen, I am a taxpayer. And I thought it was afundamental principle of American democracy that there is no taxation withoutrepresentation. I have not been represented about this war. And my people, Asianpeople, are being bombed right now." Surprisingly, the FBI agents lookeddeeply moved and blushed at my throwing this argument at them. They werespeechless. Then I understood something about the importance of having somecongruence between American liberal traditions...and our rhetoric andtactics."

The story is revealing of Ahmad's cunning in a delicate situation, and of hissly talent for turning experience into political fable. But it also suggests hishumanity, his belief in the power of reason to persuade and to elicit empathy.People like Ahmad do not come along often. That is why the publication of his SelectedWritings is an occasion for sorrow as well as celebration.

Amitava Kumar is a professor of English at Vassar College. His novel, HomeProducts, will be published next year.