Investigative journalist Josy Joseph’s book A Feast of Vultures: The Hidden Business of Democracy in India reveals that intelligence agencies had given inputs of links between mafia don Dawood Ibrahim and Jet Airways promoter Naresh Goyal in the early 2000s. Many notes were sent to then deputy PM L.K. Advani, but nothing was done—even after the government was shattered by the Kandahar hijack. In fact, soon after the hijack, Goyal was given security clearance for Jet. The exclusive extract here shows the hold Dawood has over Indian business, the questionable rise of Jet Airways and the politicians who benefited from it.

Intelligence Bureau chief K.P. Singh and his senior colleague, the joint director Anjan Ghosh, took an elevator down North Block to an official vehicle waiting in the basement on a summer day in 2002. A short distance away, at the circular building housing the houses of Parliament, members were agitated over a letter Ghosh had written a few months earlier.

It was a single-page note to Sangita Gairola, joint secretary at the Union ministry of home affairs (MHA), saying that his agency had “confirmed information of intermittent contacts between Naresh Goyal and underworld dons, Chhota Shakeel and Dawood Ibrahim, to settle financial issues. There is strong suspicion that parts of Goyal’s investments may have accrued through the help of underworld groups, prominently headed by Dawood and Chhota Shakeel”.

Ghosh further alleged that Goyal and Jet Airways had been steady recipients of large dubious investments originating from Gulf sheikhs. “Naresh Goyal’s bonhomie and close business links with the Shaikhs have been known for over two decades. These connections are believed to have been used repeatedly not only to get direct investments, but also to get a lot of tainted Indian money laundered and recycled into business in India. Much of this kind of money is generated through smuggling, extortion and similar illegal practices,” the letter said.

The letter of December 12, 2001, emerged in the media suddenly and caused an uproar. At the next session of parliament, there were vehement demands from members across parties to know the truth. One of the members, Raju Parmar, had asked a starred question in Rajya Sabha, which the home minister had to stand up and give a verbal answer to, and not just table a written reply. To a starred question, there could be instant supplementary questions that the minister had to answer. Parmar’s question was listed for May 7, the morning on which K.P. Singh and Ghosh were hurrying up to the Parliament building.

Waiting for the two senior IB officials was India’s then deputy prime minister and home minister, L.K. Advani, whose public discourses frequently revolved around the theme of how closely Indian politics was linked to the underworld. The BJP, as well as Advani, had always taken a tough position on the issue. Advani listened patiently as the two officials told him about the evidence they had of Goyal’s links with the underworld. In recent months, they had at least three telephone intercepts of his conversations with Dawood and Shakeel, the officials said, adding that there was other evidence too, according to one of the officials present at the meeting.

Advani looked shaken and determined after the meeting, the official said. “He was clear that this could not go on. I thought Jet Airways would be shut down in a matter of days,” the official said to me over a decade later. By the time I met him, sometime in 2014, Jet Airways had become a flourishing international airline, Goyal a darling of politicians and civil servants, and Advani a pale shadow of his once formidable, divisive self. One of his political pupils, Narendra Modi, would soon be the one steering the BJP to a more aggressive and popular phase.

As head of the interior security ministry, Advani was second only to prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee in the tumultuous years between 1998 and 2004, during which India tested nuclear devices, fought a limited war with Pakistan and had to deal with the repercussions of two major terrorist attacks: the hijack of a passenger aircraft and an attack on the Parliament building. Indian political rhetoric has always been shrill on the issue of terrorism, but despite decades of struggling with it, the country has no robust responses in place to deal with non-state actors.

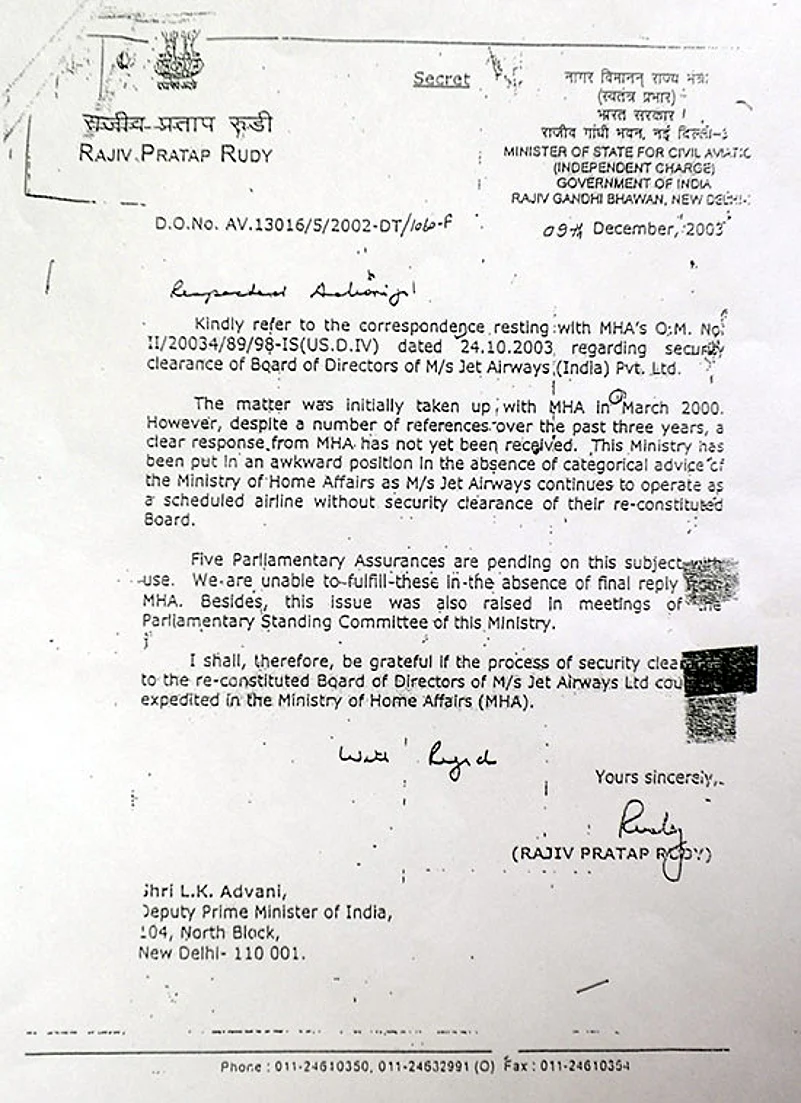

The query to the MHA

On January 31, 2000, exactly a month after the IC-814 hijack, civil aviation secretary Ravindra Gupta chaired a meeting on the issue of security clearance for air operators. In attendance were four senior officials, including Sangita Gairola (to whom Ghosh had later written the letter linking Jet Airways to the underworld). She told the meeting that, in the light of the suspected underworld links of East West Airlines and the bizarre incident of the arms drops in Purulia in West Bengal—a Latvian AN-26 aircraft flew over India undetected and dropped several hundred AK-47 rifles and more than a million rounds of ammunition on December 17, 1995—security agencies had already tightened the security clearance mechanism. The ghost of IC-814 haunted the meeting, but nobody mentioned it, at least according to the official minutes. One of the key questions was which ministry should be the nodal agency for providing security clearance to air operators.

On March 25, 2000, Gairola wrote to the civil aviation ministry, conveying her ministry’s comments to the questions raised at the meeting. Paramount was that “the authority empowered to give security clearance would be the ministry of home affairs” and that “security clearance would be required at every stage”, such as the induction of new directors to an operator’s board.

Around this time, Mesco Airlines sought permission to induct two new directors to its board. V.P. Bhatia, an undersecretary in the home ministry, wrote to the civil aviation ministry denying permission, as the two were under investigation by the CBI for forgery and falsification of accounts. In the case of the Delhi Flying Club board too, Bhatia wrote refusing security clearance to Congress party leader Satish Sharma, a close associate of the Gandhi family, because of criminal cases against him. The NDA government was sending out a clear signal: it was not willing to compromise national security, especially in civil aviation.

On March 8, 2000, the civil aviation ministry sent the details of the reconstituted board of directors of Jet Airways to Advani. It included eight non-resident Indians and five foreigners. The home ministry under Advani—Iron Man to his followers, known for his firm stand on issues—sat on it for months, even though the civil aviation ministry kept shooting off reminders. The government had given several assurances to Parliament over questions from members regarding Jet Airways, and that too was weighing on him. On January 4, 2002, civil aviation secretary A.H. Jung wrote to his counterpart in the home ministry, Kamal Pande, about the several reminders they had sent on the issue. He pointed out that Jet “continues to operate as scheduled airline, without proper security clearance for their reconstituted board”.

***

At the end of three years, IB chief K.P. Singh gave a strange twist to the entire case. He claimed his agency had earlier agreed to give Jet Airways security clearance because “nothing specifically adverse was available at that time either against the airlines or its directors on the records of the IB and the R&AW”. He wrote to the home ministry: “Whatever information has since emerged about Jet Airways or its owner Naresh Goyal from R&AW and other sources does not seem to be of the nature that would justify the withdrawal of security clearance earlier given to the airlines.” That put an end to intelligence inquiries into Jet Airways’s dubious funds and its promoter’s links to Dawood.

These exchanges between the various departments have remained buried in government files for years, and would have been there forever, had not a contact of mine handed them over to me at great personal risk.

A handful of officers in the security establishment had spent a significant part of their professional lives tracking Naresh Goyal, the origins of his business, his questionable business deals (and those of many of his friends) across the political spectrum and the underworld. With each change of government, these officials thought tough action would be taken. But Goyal continued to flourish.

Advani, BJP’s ‘Iron Man’ failed to show his mettle in handling l’affaire Goyal

Singh’s note omitted no facts. Before absolving Goyal, he said that the Jet Airways owner “appeared to have earned his wealth through smuggling and other illegitimate means and that the airlines was probably investigated for FERA [Foreign Exchange Regulation Act] violations”. Singh also pointed out that Goyal had in the past been accused of adopting unfair business tactics to undermine rival airlines, such as purchasing of union leaders and exploiting political connections. “Such tactics are, however, not uncommon in a highly competitive business milieu and while such traits reflect unfavourably on his professional ethics, they do not impinge on national security,” Singh wrote.

His note referred to the input given a few months earlier, detailing Goyal’s links with the Dawood gang. It added that the inputs “were mainly procured from the R&AW” and that the intelligence agency had “indicated their inability to further develop the information already given by them” except to say that Goyal “had earned his wealth through smuggling and other illegitimate means”. Singh didn’t mention the IB’s own intercepts of talk between the Dawood gang and Goyal—intercepts that his own agency had earlier reported to the government.

Curiously enough, the home ministry—even Advani—raised no objections, though it was only months earlier the home minister stood in Parliament to assure the house of appropriate action.

Singh’s letter contradicted what Anjan Ghosh had said a few months earlier. “It was a simple case, and there was no doubt about what the ministry’s position should have been,” one of the officials who dealt with the case told me.

On the IB chief’s cue, the home ministry gave up its authority to issue security clearance and instead left it to the civil aviation ministry. Of all the records I have gone through regarding security clearances for private air operators, Jet Airways’s is the only case where the home ministry gave up this right.

Mukesh Mittal, a director in the home ministry, wrote to the civil aviation ministry that they had found “certain adverse inputs against Shri Naresh Goyal, chairman of the Jet Airways”, and attached a gist of the inputs on him, which repeated almost all the points raised originally by Anjan Ghosh and K.P. Singh, and reproduced Ghosh’s letter almost verbatim. “Report, though unconfirmed, ascribes this exponential growth in the company’s holding due to money transfers through hawala (illegal money transfer) channels,” the note concluded.

After this indictment, Mittal’s note concluded: “In view of this position, the ministry of civil aviation may please consider the proposal keeping all aspects in view and take an appropriate decision.” He added that the order has been issued with the “approval of the home secretary”.

Once again, Advani did not seem to have any comments on the issue. Yet, he cannot be singled out for blame in a system where ambivalence and obfuscation—not positive articulation—mark the conduct of business.

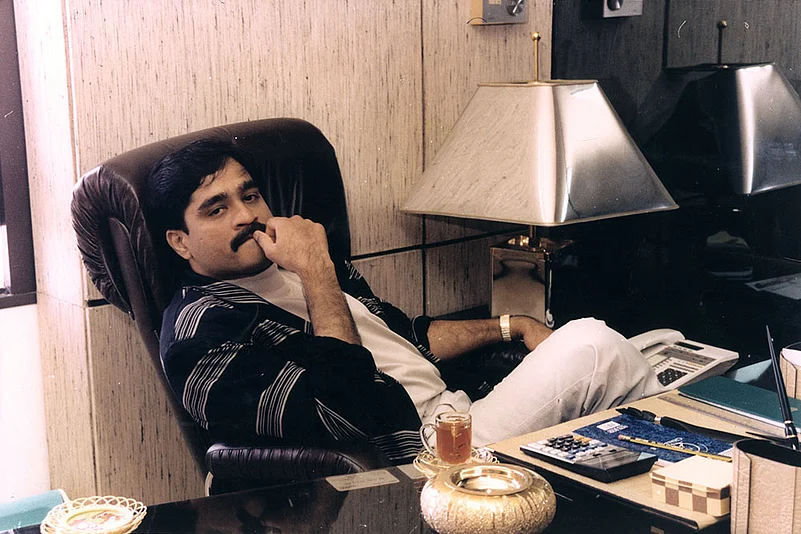

Despite the government’s almost clean chit, the intelligence agencies never closed their files on Jet Airways. As of 2015, I had confirmation the case was open. The former chief of an intelligence agency said the case could never be closed. “It is a test case for us, and it is a shame that, despite such overwhelming evidence, we couldn’t take any action,” he said one evening, as we discussed the deep roots of the underworld and criminals in Indian politics and business. He argued that the extent of Dawood’s network had not yet been revealed to the public.

Over the years, intelligence agencies have been gathering significant evidence of Dawood’s connections with many political leaders and businessmen from his hiding place in Pakistan. He has evolved very sophisticated ways of keeping in touch with the Indian elite and businesses. A Union minister in Dr Manmohan Singh’s UPA government, which was in power between 2004 and 2014, had been exchanging notes with him through a resident of south Delhi, who was also suspected to be a bookie manipulating cricket games. According to several intercepts by R&AW over the years, the bookie had been negotiating through the minister for Dawood’s return to India. The don was willing to spend a few years in an Indian jail if he was allowed to return. The Karachi-based don had never felt at home in Pakistan; it was in India that he built his fortunes and followers. In these intercepts, the south Delhi resident is heard promising Dawood and his key aides that the minister would try to get the government to offer Pakistan a deal to extradite Dawood. Officially, India had been demanding that Pakistan return Dawood to India, but Pakistan continued to deny he was in its territory.

A prominent regional political satrap from Uttar Pradesh used to receive messages from Dawood through couriers sent from Mumbai, according to dependable intelligence operatives who have watched it closely. Dawood and his aides would send their messages to a Mumbai-based Muslim preacher, and he in turn passed on the information through trusted youngsters recruited from Uttar Pradesh. The couriers have been used dozens of times in the past decade, an official claimed.

He lingers on in movies, politics, betting, drug smuggling, land deals, construction—and in the imagination of the security establishment. In the summer of 2013, when the police forces of Delhi and Mumbai exposed the widespread practice of illegal betting and fixing in the cash-rich Indian Premier League, they said the Dawood gang ultimately controlled the betting syndicates. Delhi police charged several people, including former Indian cricketer S. Sreesanth, under the draconian Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act (MCOCA), saying that they had indulged in spot-fixing during matches at the command of Dawood and his key aide Chhota Shakeel. Though the evidence was untenable, allegations of links to Dawood is an effective ploy to strengthen and sensationalise any case, and also to cover up the agencies’ weak investigation skills. In 2015, a Delhi court threw out the Delhi police’s claims. Dawood has, meanwhile, grown into an enigma, a nightmare, and an unavoidable reality of the daily existence of modern-day India.

That said, he also survives because of deep-rooted contacts within the security establishment itself. On July 11, 2005, a joint team of Mumbai and Delhi police intercepted a car in the national capital and arrested Vicky Malhotra, a key aide of Dawood’s rival Chhota Rajan, who was wanted in numerous criminal cases, including murder and extortion. Surprisingly, accompanying Malhotra was Ajit Doval, a former chief of the IB and one of India’s most celebrated spies, who went on to become the national security advisor (NSA) to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. Some intelligence sources said Doval, despite his retirement, was part of an ongoing IB operation to use the Chhota Rajan gang to target Dawood. Some said Doval was acting on his own. Investigations revealed that Dawood had contacts within the Mumbai police and that they had created an alert about Malhotra and thwarted Doval’s operation. The police promptly sacked an inspector who was in touch with the Dawood gang. A few days after this drama, Dawood’s daughter married the son of famous Pakistani cricketer Javed Miandad. The reception was held at Dubai’s Grand Hyatt hotel. Speculation was that Doval was planning to target Dawood and his gang if they attended the Dubai reception. But Dawood turned the tables on him and one of India’s most celebrated spymasters was caught on a Delhi road with a criminal.

Regarding the Dubai reception, the US embassy in New Delhi cabled to their headquarters: “Like a bad dream, terrorist and underworld figure Dawood Ibrahim returned to the headlines of India’s media in July when his daughter married the son of a famous Pakistani cricket player. An upscale wedding reception brazenly took place at the ostensibly American-run Grand Hyatt hotel in Dubai on July 23. Ibrahim, India’s most wanted man for the 1993 Bombay bombings that killed hundreds, and a US Specially Designated Global Terrorist, reportedly did not attend the event. One media outlet mentioned, however, that Ibrahim, believed to be living in Pakistan, travelled on forged documents to witness the nikah (wedding) ceremony of the couple on July 9 in Mecca. The wedding and subsequent reception generated intense interest in the Indian media, which reported that Indian police and security services were shadowing business, entertainment and underworld figures from India who might try to attend the reception. In the end, no prominent Indians actually showed up in Dubai. The manner in which Ibrahim could so blatantly stage such an event has infuriated our Indian contacts.”

Dawood tripped up Doval, getting him caught with a criminal on a Delhi street

To succeed in India, it is important to have friends across the political spectrum and deep inside the system. The end of right-wing rule in the summer of 2004 didn’t change much for Naresh Goyal—quite unlike the fate of East West Airlines when the Congress lost power almost a decade earlier.

Goyal had friends in all the right places. One of the key regional parties in the new ruling dispensation, the UPA, was Sharad Pawar’s Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), which, according to New Delhi’s political grapevine, insisted on getting the civil aviation portfolio. Praful Patel, a flamboyant businessman whose family made its fortunes in tobacco, and who is known to be a key aide of Pawar’s, became the civil aviation minister.

Around the time that the new government was coming to power—when India had yet not permitted its private airlines to fly abroad—Jet Airways began applying for slots at the London, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Bangkok airports. When the matter came up in Parliament, Patel said the airline was doing all of this at its own risk. What he did not say was that a committee appointed by the previous government had submitted a detailed roadmap for expansion and modernisation of the aviation sector. And that an exercise had already been initiated to implement just one of the recommendations of the committee: permit private airlines to fly abroad. This was not publicly known, nor was Parliament told about it. Within months, Jet Airways became an international airline.

As Jet Airways prepared to launch its services in the US, Maryland-based Jet Airways Inc filed complaints before various authorities, asking that the Indian company be denied permission to fly to the US, accusing it of trademark infringement. Its CEO and president, Nancy M. Heckerman, also said that Jet Airways of India was an Al Qaeda company. Her objections were marked to the Indian government by the US, asking for clarifications. Within months of the May 23, 2005, complaint, the government of India officially communicated to the US that there were no security concerns with respect to Jet Airways.

Even as the airline was awaiting US clearance, similar queries about its links to dubious outfits emerged from the governments of Singapore and UK in 2006 after a Jet Airways employee in London, Amin Asmin Tariq, was arrested for alleged links to the foiled bid to blow up transatlantic flights with liquid bombs. New Delhi was consistent in its stand: Jet Airways posed no security concerns. Officials who had been watching Goyal and Jet Airways for years told me that the government’s enthusiasm was surprising. “Not only did the government give a certificate of good conduct to them, but it put its diplomatic might behind the company,” said one senior official in the security establishment. Another one said the political establishment may have given a clean chit, “but the Indian intelligence agencies can never close the case”.

In January 2006, Jet Airways offered to take over Air Sahara, part of Subrata Roy’s Sahara group. Much like Goyal, Roy too had made a mysterious climb up the big-stakes ladder. In March 2014, the Supreme Court of India sent Roy to jail in a running battle between the Sahara group and the country’s capital market watchdog, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), over inconsistencies in the accounting of Rs 24,773 crore that it claimed to have collected from 3.1 crore investors. The addresses of most of these subscribers couldn’t be verified, and Roy’s legal team was accused of trying to mislead the market regulator and courts. As of mid-2016, he continues to be in jail.

Let’s return to his airline interests, though. In January 2006, Jet Airways offered to buy Air Sahara for Rs 2,300 crore in the biggest deal yet in Indian aviation history. There was concern among some analysts that Jet was overpaying. The civil aviation ministry gave an in-principle approval, but concerns about security clearance came up again in the context of Goyal joining the Air Sahara board. A minister in the UPA government took aside the chief of an intelligence agency involved in the matter and told him to be meticulous in dealing with it. “I was surprised because he was known to be a Goyal man, and here he was telling me to be firm with Jet Airways,” the official told me. As instructed, the agencies were meticulous, thus delaying the process, and as a result, the deal collapsed. Both sides filed lawsuits against each other. Strangely, a day after the deal officially collapsed, Goyal’s security clearance came through, this time from the home ministry.

Sahara’s ventures were running in losses, and the group had been scrambling for cash. It restarted negotiations with Jet. This time, a desperate Sahara settled at Rs 1,450 crore, almost 40 per cent less than the original offer. “I have rarely seen Subrata Roy so helpless,” one of the key negotiators in the deal told me during a meeting in Mumbai. “Nareshji was in complete command.”

As the Jet Airways juggernaut powered ahead, the Indian aviation market—like the Indian economy itself at that time—was exploding. In 2000-01, a total of 1.4 crore passengers flew in Indian carriers; the number jumped to 4.5 crore by 2009-10. Many of India’s cattle-shed airports were overhauled and private businessmen entered aviation, reaping rich rewards.

Around the time that the Jet Airways-Air Sahara deal was being negotiated, the government decided to overhaul Delhi’s old airport. Delhi International Airport Private Ltd was incorporated with the government holding 26 per cent of the shares, the rest held by a consortium of private players, including Fraport and Malaysia Airports Holding Berhad. Leading the private consortium with 50.1 per cent stake was India’s GMR group. Such public-private partnerships (PPPs) are among the defining features of India’s efforts to reform its economy, especially the crumbling infrastructure. The Delhi airport symbolises India’s economic resurgence, its quest to modernise infrastructure, the partnerships that shape ‘new India’ and the questionable deals undermining all of it.

In July 2004, when bids were invited for redevelopment of the airport, GMR was not among the front-runners. But in January 2006, it was the consortium led by GMR that was appointed to redevelop the 5,106-acre Indira Gandhi International Airport. Then, in August 2012, government auditor CAG released a damning indictment of the airport project, accusing the government of blatant favouritism to the joint venture (JV), resulting in public losses running into billions of dollars. The CAG also found that a clause limiting the JV’s terms to 30 years, to be extended by another 30 years through “mutual agreement and negotiation of terms”, was mysteriously omitted from the final contract, making it easier to extend the JV contract. This was particularly ominous because it was a decision arrived at by the UPA council of ministers. The airport operator had been allowed to lease land for commercial exploitation at a far lower rate than even the amount government agencies were paying. For a meagre Rs 100 as annual rental and a one-time payment of Rs 6.19 crore, the operator had been allowed to use land with earning potential of Rs 1,63,557 crore over the concession period of 58 years. Each passenger flying out of the airport was, and still is, forced to pay a user fee, which was not part of the contract provisions. The 44-page report is packed with an enumeration of favours to the private consortium. The report resulted in the usual round of protests and outrage, which died out in a few days.

Slide Show

Working through college with a job at a relative’s travel and ticketing agency, Naresh Goyal moved on to handling sales, marketing and logistics for various international airlines in the late 1960s and through the 1970s. In the 1990s, with the opening up of the Indian economy, he ventured out on his own, and he launched Jet Airways, seen as a major success story. The political connections that helped the rise have always been whispered about.