This is a tour de force. I have been mesmerised. Although it is only two months into 2017, I am sure this is going to be my choice for book of the year. Even the most impressive of historical figures are cardboard characters. We know how they loomed over their age; we know the paths they blazed; we know their enduring legacy. But do we know them as human beings, with foibles like you and me, as tortured at times as you and I are, as exulting in private over their public achievements?

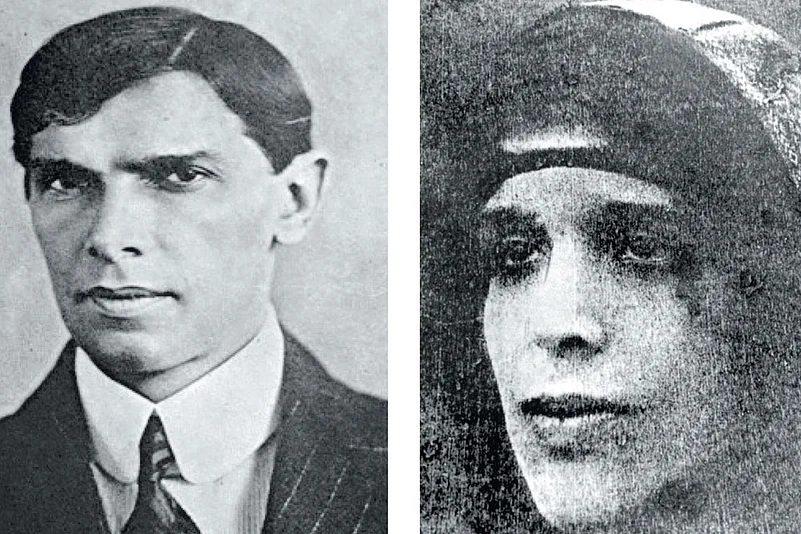

Also, while a Noor Jehan or a Jodhabai might peep out in history books from behind her husbands’ persona, rarely do we encounter the spouse as flesh and blood. Here, however, we have Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Great Leader, and Ruttie Petit, his wife, portrayed with great sympathy, even empathy, but, withal, tragic, emotionally unfulfilled personalities, whose fabulous wealth (in Ruttie’s case) and great fame (in Jinnah’s case) count for nothing beside the personal agony each had to endure, brought on by incompatibility of temperament but bound together by a fascination for each other, fired by a shared passion for the politics of the freedom movement.

The story Sheela Reddy has to tell is not new. But her way of telling it—in lucid, fast-paced prose, sentimental as a Mills & Boon romance, comprehensive as a Tolstoy history—is all her own. She has drawn extensively on the numerous biographies of Jinnah, particularly Hector Bolitho’s justly acclaimed work, and the memoirs of Jinnah’s associates, especially M.C. Chagla’s Roses in December. She has then woven these studies and reminiscences into the personal correspondence of Ruttie with her closest confidantes, Sarojini Naidu and her two daughters, starting from before Ruttie had even reached her teens and leading to the last letters of her short 29 years of life, including a few to her much-loved but distanced husband. Blended into this intimate portrait of a doomed relationship are Ruttie’s frantic notes penned to the one man, Kanji Dwarkadas, who was the only one really personally close to both the tragically mismatched protagonists.

And all the while, we sail along the currents of history-in-the-making, with the writer deftly manoeuvring to keep the focus on a deeply moving yet heart-breaking love story against the backdrop of lightly sketched but dramatically told political events. Sheela Reddy’s achievement lies in keeping Jinnah, and more especially Ruttie, centrestage throughout her 400-page tome while keeping the reader enthralled with the political drama being played out in the wings, but never allowing the political to overwhelm the personal, unless, as at times, the political is the personal. Indeed, politics was so integral to their lives (at least until they started drifting apart) that it is a tribute to the writer that even when politics is dominating the scene, she maintains the balance between Mr and Mrs Jinnah instead of yielding to the temptation of letting Mr Jinnah run away with the narrative.

What also comes alive is the Bombay of the late 19th to early 20th centuries. One almost hears the clip-clop of the horses’ hooves as they pull along the Victorias of the rich and famous. Horns start sounding as motor cars start rolling down Bombay’s roads at the turn of the century. The country is astir with intimations of a soaring urge for freedom. Nowhere is politics more alive than in Bombay, with 40-year old Jinnah as the rising star. A great friendship is struck between the fantastically wealthy Sir Dinshaw Petit, third in a line of Parsi baronets, ever seeking the patronage and favour of British rulers, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the supremely self-confident, if self-made, lawyer, implacable opponent of British rule and ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. Jinnah is often at the Petit mansion, but not paying much attention to Ruttie, a pretty, precocious, vivacious and spoilt child, with her every little whim indulgently granted. The avuncular Jinnah barely notices her as she grows up to all of sixteen, the cynosure of all eyes for her beauty and high spirits, and her passion for books and poetry—and politics.

Suddenly, the dour confirmed bachelor is captivated. Very properly he asks her father for her hand in marriage. Sir Dinshaw is horrified. How can he possibly let his adolescent daughter, still in her early teens, marry a man two decades older than her—that too not a Parsi. Understanding only too well that his community would never stand for it, he puts his foot down. His darling daughter, the very apple of his eye, turns hostile to both her father and her mother, locks herself up in her room and secretly corresponds with a man twenty-four years her senior.

At exactly the same time as he sets his eyes on Ruttie, Jinnah starts emerging at the very summit of the national movement, the acknowledged bridge between the Muslim and Hindu communities and the torch-bearer of the 1916 Lucknow concord between the Congress and the Muslim League. Not even the return to India from South Africa the previous year of M.K. Gandhi dims his star, annoyed though he is with Gandhi addressing him as a Muslim, not a national, leader. Over the next two years, while Gandhi is still finding his feet in Indian politics, Jinnah grows immensely in stature, his jurisprudential skills coming to the fore as he prepares India and the British for the fundamental change in relations between India and the Empire that Jinnah and most Indians believe the honourable British will promote at the end of the Great War, to which India have made such a major contribution.

It is at the very summit of Jinnah Phase I that Ruttie, reaching in 1918 the age of 18—the age of consent—steals out of her palatial home to nominally convert to Islam and marry Jinnah at his dowdy, ill-kept South Court mansion. There is, however, little overt emotional bonding between them—Jinnah preferring to pore over the dozens of newspapers that he loves reading rather than spend his evenings with his new wife—and the looming presence of Jinnah’s sister, Fatima, robbing the relationship of what little intimacy there is between the romantic young bride and the unsentimental middle-aged bridegroom. Yet, even if Ruttie’s husband knows nothing of murmuring sweet nothings into her ear, she loves his political monologues and invariably attends all the public meetings where he speaks. There is a gripping episode of her making an impromptu speech in pouring rain to an adoring mass, but that little adventure is snuffed out when Ruttie discovers, from a disturbed look in Jinnah’s eye, that he feels cheated at her stealing his public thunder.

But within months of his winning his lovely, captivating bride and simultaneously climbing the summit of his ambitions as the older generation yields to the generation that thirty years on was to bring us both Independence and Partition, Gandhi displaces Jinnah after the Rowlatt Acts and the Jallianwallah Bagh tragedy, leaving stranded Jinnah’s brand of negotiated gentlemanly constitutional change. He has no stomach for Gandhi’s agitational methods, nor for his alliance with the Khilafatists, whom Jinnah regards as backward-looking Muslim chauvinists. But Jinnah’s moment has passed. The youth of the country, Hindu and Muslim, are looking elsewhere. Even if his older friends like Motilal Nehru and Tej Bahadur Sapru are in sympathy with his parliamentary approach, at which he is the master, the collapse of the 1927 Delhi pact he has made with his Congress friends, and the distancing of his erstwhile Muslim followers from his brand of inclusive (if elitist) politics, leave him as deserted on the political shore as the accelerating collapse of his marriage with Ruttie.

In retrospect, the collapse of the marriage could be seen to have begun with the unwanted birth of their daughter. The parents so neglected her that the baby did not even have a name till she named herself Dina after her grandmother at the age of nine. To begin with, Ruttie stood by her husband through his tribulations with the Gandhi-led Congress, but once she found her freedom to flee to Europe on holiday without her husband, the marriage started unraveling and her interest in politics withering. She hates his becoming more and more Muslim to worm his way back to the favour of the community.

Sheela Reddy is an able raconteur. The reader is made to feel a personal witness to both the private life and public presence of this unusual couple. It, therefore, behooves this reviewer to not reveal the scores of telling episodes—personal and political—that mark this telling of the ten tumultuous years that covered their descent from a giddy “marriage that shook India” to a tragic, drug-induced apparent suicide when she was but just 29. The epitaph to their life together is in Ruttie’s last letter to J (as she called him): “Try and remember me beloved as the flower you plucked and not the flower you tread upon. The measure of my agony has been in accord to the measure of my love.”