Silent in the field

A butterfly was flying

Then it fell asleep

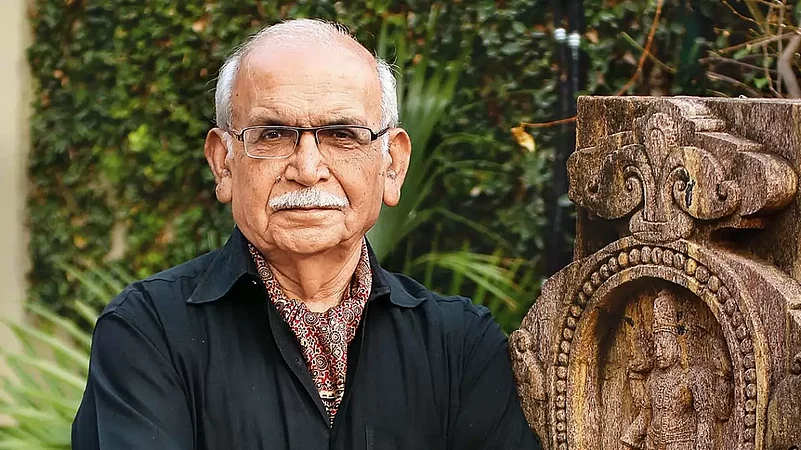

Brijinder Nath Goswamy walked gently, talked gently, silently! When he bid adieu to our world on the morning of November 17, 2023, the sannata (silence) befell the universe of art, its history and the ways of its interpretation. At ninety, his presence was precious and prescient. He left us, as if, while listening to Kumar Gandharva’s self-composed bandish in raag Shuddha Shyam—silent in the field:

मोय बुलायके पूछो ना रे

अजब रीत तेरो हैगा रे ||

समझ ना परे उलझायो रे

का कसूर मेरो हैगा रे ||

(Call me and at least enquire about me; strange are your ways, instead of making things easier, you complicate them, what is my fault?)

In Amit Dutta’s extraordinary short film The Museum of Imagination: A Portrait in Absentia (2012, 20 minutes) on Goswamy, we see him sitting in solitude listening to the great vocalist he was long fond of. Though I was fortunate to have met the legendary art historian in person, listening to his erudite and yet accessible speeches a couple of times, and through reading of his books, my ‘direct’ and ‘intimate’ contact with him has been through Dutta’s two films besides Nainsukh (2010, 90 minutes). Among the two films, one is already referred to above, and another is Field-Trip (2013, 22 minutes); their reference is intended.

Goswamy incessantly and rigorously prodded the ‘process’ and pursued it. His quest was to capture the ‘essence of essence’. In the film The Museum of Imagination, we see pages from a book with paintings on one side and their interpretations on the other. Among several examples, one provoked the title of my homage to the great scholar Goswamy, who describes the painting:

“The very picture of devotion, bare torsoed, head bowed, legs crossed, and hands folded, Jayadeva stands at left with the implements of worship placed before the lotus-seat of Vishnu, who sits there, blessing the poet who wrote: ‘this perfect invocation’ that joyously ‘evokes the essence of essence’.” (Emphasis added).

Through these two short films, Dutta illuminates for us this ‘essence of essence’ in their niches of solitude and silence. In its introduction, the film The Museum of Imagination informs us:

“Prof. B N Goswamy is one of the foremost authorities on Indian art and culture. As an art historian, his work has covered a wide range, and has influenced much thinking, especially in the area of Pahari Painting. In the year 2011-12, we recorded long conversations with him about his life and work. Interspersed with his talks were also some silences. In this film, we have put some of those moments of silence together. All that has been added are some sights and sounds that have been a part of his life.”

Over many years, Goswamy went on to become an integral part of the life and work of Dutta, the artist-filmosopher. He became his mentor and a guru. The Jammu-born Dutta lives in Palampur in the neighbourhood of the Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh. It is here Dutta found the inspiration to make a film Nainsukh on the 18th century painter from Guler about whom Goswamy has written a substantial book Nainsukh of Guler: A Great Indian Painter from a Small Hill-State (1997: Artibus Asiae, Zurich; Niyogi Books, Delhi). Prior to this book, the revered professor had written another authoritative book Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India with Eberhard Fischer, former Director of the Zurich-based Museum of Rietbert, which had sponsored the film Nainsukh.

However, it is in the film Field-Trip that we see Goswamy embarking upon his research work (in the 1960s) among the genealogists at the Hindu pilgrimage site of Haridwar and elsewhere. He is in search of the roots of the Guler family of painters, particularly Nainsukh, his brother Manaku and their father Pandit Seu. During one of his field-trips, he had found massive archives of Bahis, registries of records written on paper by priests or purohits who worked as genealogists attached to families. Through his rigorous fieldwork, Goswamy was able to trace the family tree (vamsha-vriksha) of Nainsukh.

Goswamy’s search doesn’t stop there. He meets one of the descendants of the Guler painter and his quest leads to more questions. In the film Field-Trip, we find him sitting with Nainsukh’s descendant Chandulal’s son to whom he poses a question: “I’m interested in your sisters because commonly in Pahari painting tradition, women’s or girls’ names don’t occur. I remember when Chandulal showed me works, it greatly impressed me that Pushpalata’s and Pancham’s hands were very clean. Nothing to take offence, but probably better than their brothers’, wasn’t it? It felt very good. So in the past, didn’t any women or girls paint?” Living in the pleasant Himalayan Valley, the young descendant’s answer is down to earth: “In those days, women worked quite less. For instance, when the artists worked, they helped them by preparing colours, drying, powdering pigments, etc.” (Reproduced from the English subtitles in the film)

Since I hail from a village in Kutch, I was delighted to see the book A Place Apart: Painting in Kutch, 1720-1820 (OUP, 1983) that Goswamy wrote with Anna Dallapiccola, an eminent scholar of Indian Art History from the University of Heidelberg, Germany. In their preface, the authors inform us that they found the hitherto unseen paintings from Kutch through H M Fuest of the Galerie Fuest in Heidelberg and say, “We were able to spend a great deal of time with these works that no one seemed to have heard before, but that clearly demanded for themselves such full attention.” The catalogue of numerous colour and black & white plates adds to the repertoire of Kutch paintings.

The paintings at this German museum might be the ones done by travelling painters and not the local Kutchi artists or craftsmen, the author of the book on the Wall Paintings of Kutch, Pradip Zaveri, tells me. Through his extensively researched photographs of these paintings, Zaveri has saved them at least in our visual memory of past and future, since many of them were destroyed during the devastating 2001 earthquake in Kutch.

In his column in The Tribune, Goswamy has often written about Kutch, and his articles are now part of the book Conversations: India’s Leading Art Historian Engages with 101 Themes & More (Penguin Books, 2022). This book is a collection of essays from the ‘Art and Soul’ column he wrote for 25 years in the daily The Tribune published from Chandigarh, his beloved hometown. He also refers to the brutal calamity that destroyed many art objects in Kutch.

For decades, Goswamy gently held our finger, and walked in search of an ‘essence of essence’… a pure bliss!!

Amrit Gangar is a Mumbai-based film critic, theorist, curator, author and historian