What a delight to find a history of Indian capitalism packed with enough econometric and statistical data to satisfy academics, but still accessible to lay readers. Roy, based at the London School of Economics, is a quiet, scholarly figure and no polemicist. Yet his book explodes deeply held nationalist myths.

First to go is the notion that pre-colonial India was a land of economic milk and honey, just waiting to be plundered by the wicked East India Company. We learn instead that trade and capital costs were exorbitant, with monopolistic Indian bankers charging interest rates as high as 40 per cent, compared with only 6 per cent in England. There were no indigenous machines or machine tools, and labour was tied to the land. The “great divergence” between India and the West, with its scientific and industrial revolution, would have happened anyway.

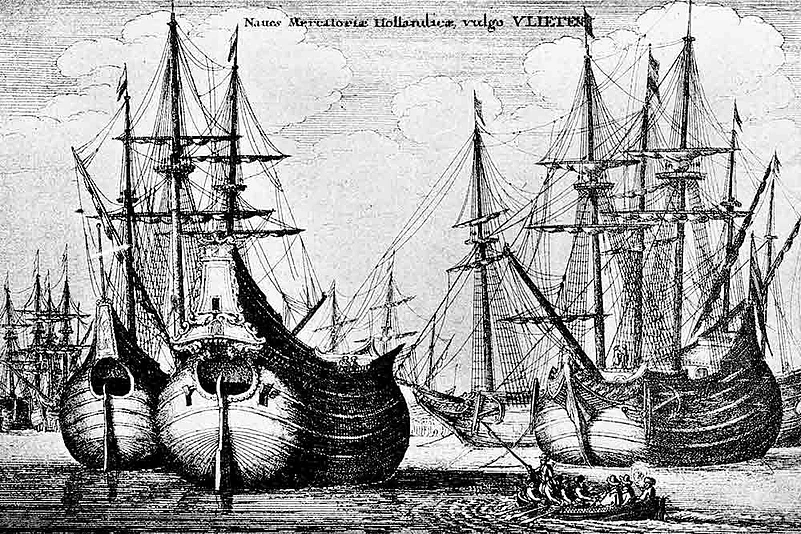

What the colonial impact did bring about was migration of businesses from declining inland centres to the flourishing new port cities founded by the East India Company. These became centres of cosmopolitanism, with old caste affiliations submerged in new trading ventures to China and West Asia, protected by British naval control of sea routes. Newly urbanised business communities like Marwaris and the Parsis led banking and factory industrialisation, underpinned by British commercial law, limited liability and joint stock companies.

Roy argues persuasively that, far from de-industrialising India by flooding its handloom markets with factory-produced British goods, the colonial encounter laid the foundations of India’s own industrial revolution in the second half of the 19th century. It did this by maintaining global open markets that enabled Indian enterprise to trade successfully across the world and then plough the profits of trade into buying foreign technology needed to set up India’s infant industries.

The figures are impressive. Bank deposits rose from virtually zero in 1870 to 12 per cent of the GDP by 1935. Factory employment during the same period leapt again from zero to 2 million, comparable to Japan or Russia. Colonial India led the developing world, not only as its largest textile producer, but also in iron and steel, producing half of all steel made outside Europe, North America and Japan. Thanks to their enormous profits in Britain’s two world wars, Indian capitalists like Tata and Birla formed conglomerates and diversified into new sectors like paper and sugar. In 1947, Indian cities boasted some of the best schools, colleges, hospitals, banks and insurance companies outside the Western world.

Roy dismisses the notion that British employers were any more exploitative than Indians. “The European planter,” he says, “did not do anything the Bengali zamindar would not do to a peasant whose rent was in default, which was to beat him up in a special room made for the purpose.” He is equally dismissive of the nationalist myth that Britain drained Indian wealth through foreign remittances. Instead, imperial openness made it possible for India to import what has always been its most scarce resource, capital. It was foreign investment that financed the railways, which in turn stimulated the grain trade, bringing down transport costs and increasing the flow of price information to farmers. That, in turn, boosted agricultural exports, which earned more foreign exchange to re-invest, a virtuous circle of profits fuelling growth.

As for the alleged ‘drain’ of foreign remittances by Brits in India, they were more than offset by India’s consistent trade surplus with Britain throughout the colonial period, a surplus which balanced purchases abroad by the colonial government and the private sector. The Raj, in effect, functioned as a giant customs union, with free movement of goods, capital and labour within India and across the wider British Empire.

All this, Roy tells us, ground to a halt after independence, with the sad story of Nehru’s socialism shutting down the globalisation and trading opportunities that had been the engine of economic growth under the Raj. Indian nationalists came to power with a prejudice against traders, and the result was the Permit-Licence Raj that not only killed off trade, but also cut off Indian industry from the foreign technology, capital and markets it needed.

Ironically, the resulting abysmal rate of growth was only reversed after 1990 by a gradual return to the cosmopolitan openness. India again has the capacity to buy knowledge from the world and to sell its services abroad.

“Colonialism,” Roy concludes, “was bad politics”, but its economic openness was good for business. “Indian nationalists,” he complains, “made people believe that colonial rule was bad because the open economy had made India poor. There was an unfortunate muddle between market liberalism and political liberty, for which post-1947 India paid the price.”