Buoyed by the reputation of the RAND Coeporation and the rigorous research ofAmerican academia comes another book on India's emerging nuclear policy.AshleyTellis, an American of Indian origin and currently, the adviser to the USambassador in India, begins with India's overt nuclear tests in 1998 and analysesits nuclear ambitions.

Disagreeing with the government's view that India is a nuclear weapon statein the true sense, Tellis senses that thegovernment is at a crossroad of indecision, pulled in different directions by ahistorical commitment to disarmament, economic constraints and world pressure onthe one hand, and the dynamics of nuclear strategy and stability on theother.

Running to 765 pages of text, the guts of the book lie in chapters IV and Vwhere Tellis derives what he believes will beIndia's 'force-in-being' based upon how India looks at the world, and how theworld influences India. Other analysts have listed the motivations of nuclearweapon states to varying mixes: the drive for world prestige, nationalsecurity needs and pressures from the techno-bureaucratic lobby. Having kept the'option open' for 34 years (1964-98) and constantly chided by its ownstrategists for being a victim of nuclear apartheid, the urge to world statuswas an undeniable factorin May 98.

So also were the 34 years spent in China's nuclear shadow, in the last 10years of which Pakistan was given a working bomb design -- an NPT violationdiscovered not by Indian intelligence, but by an alert US non-proliferationlobby. The third factor is the discernible push to weaponize from the atomicenergy establishment and the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO).

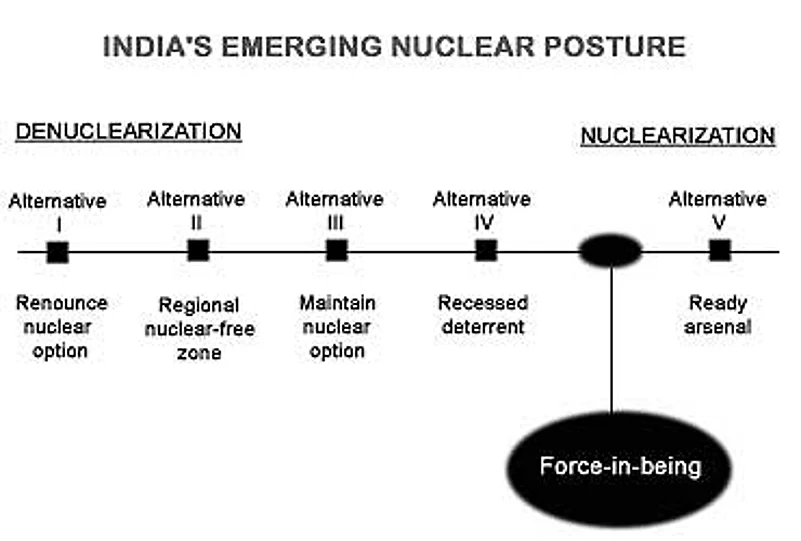

In chapter III, Tellis examines five choices before India, laid out in ascendingorder of assertiveness.

Having ruled out choices one to three for their unacceptability to India, thefourth choice, of maintaining a RecessedDeterrent, short of developing a ready arsenal, finds favour with the author,and there are some cogent reasons. Tellis subtly refers to the absence ofall the other preparations that should have accompanied explosive testingand the list is staggering - they include a lack of fissile material,delivery vehicles, supporting infrastructure, procedural systems, ideationalsystems and strategic defence. If these have to be constructed, to create ameaningful deterrent, why not decide to delay deployment?

The pitfalls ofthe fifth choice are clear -- unravelling of the NPT, and the resultantopprobrium, a worsening of India's strategic neighbourhood, and living with ahostile USA. So according to Tellis, the choice for India lies between IV and V.

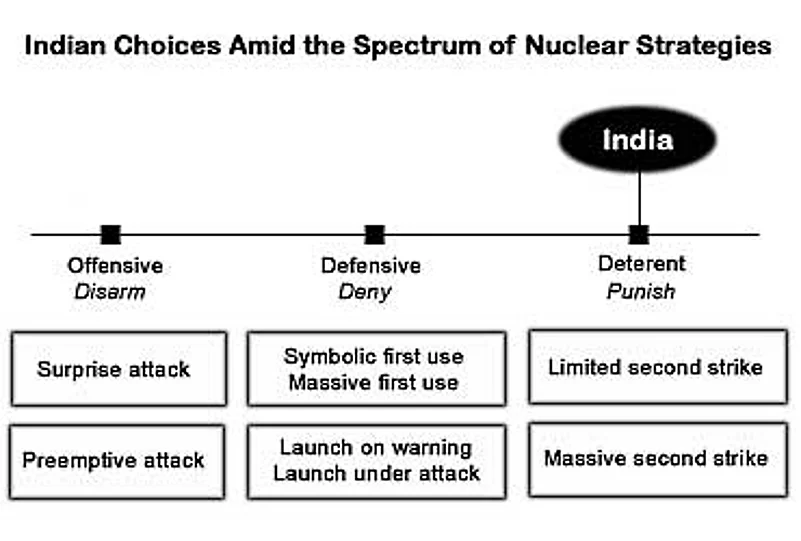

In the central section of the book, the political premises of the Indo-Pakistan calculusare well argued, casting serious doubt on whether Pakistan can ever get outof conventional asymmetry and defeat by threatening nuclear annihilation.The unsettled border with China is less a cause for worry than Delhi's needto balance the Asian power equation with a nuclear second strike capability.

Tellis's views on the Indian arsenal are disturbing. The controversy overyields is well articulated with the US government concluding that no fusiontook place on May 98, that the Indian flying plate bomb design can onlyguarantee 15 kt. With the fissile material available, the arsenal can benomore than 150 simple fission warheads - enough to definitely deter Pakistan,but just about enough to create second strike deterrence against China. SoIndia ends up in the dilemma of the weak attempting to deter the strong, butnot perhaps being able to rationally make good the deterrence threat. In theabsence of simulation, it remains a value judgement that the pain India caninflict is worse than the gain that accrues to China. Despite the manycriticisms of India's nuclear posture, Tellis writes with a courtesyand politeness that no Indian would have bestowed on many governmentalpolicies and lapses.

How will the world adjust to the South Asian arsenals? India cannot becompared with the rogue states Washington has in mind, says Tellis, and theNPT could be adjusted to include India and Pakistan, or has 9/11 ruinedthings for Islamabad? The US may adjust the international regime if Indiakept it 'small, stealthy and slow'.

A massively researched book -- it'sunlikely that any Indian researcher will find his name absent in the foot notes-- and if at all there is a criticism, it is that assumptions on nucleartechnologies and arsenals in a hostile environment can rarely presume thatboth are completely under human control, for they have a life of their own. While the book is exhaustive on what the Indian state might do, it is notclear what the nuclear weaponry will do to the state. At Rs. 895 a copy,OUP has done the Indian strategic community a service by making availablean Indian edition.