Dawn in the south Indian pilgrimage town of Sringeri, in Karnataka. It’s a brief moment of stillness and cool. Walking sleepily in the half-light, I’m startled by something coiled on a veranda—a snake, which, from the looks of it, is drowsy too. But as my eyes adjust to the rising light, I look again and laugh: it’s not a snake—merely a coiled rope, left by a man who’s been fixing the tiled roof.

This bit of self-deception—mistaking a rope for a snake—is an occasional false alarm in Indian life. It’s also among the most well-known, even hackneyed, examples cited in Indian philosophical thought. Its purpose is to show that, although the sensory world is out there, our imaginations sometimes intervene between us and reality. Our minds, in other words, are tricksters. At the same time, what we perceive—the snake superimposed on the rope—has real power. As another famous example from Indian philosophy runs, even someone who only thinks he has been bitten by a snake can die from shock.

Mistakings pervade Hindu philosophy, which is full of metaphors of concealment and obscuration. Many serve as examples of maya, the reality that substantially and unarguably presents itself to us but whose true nature remains elusive because of the limitations of our consciousness. Push aside this slippery, illusory world and something pure and constant is revealed: god, the divine, or the universal spirit—Brahman.

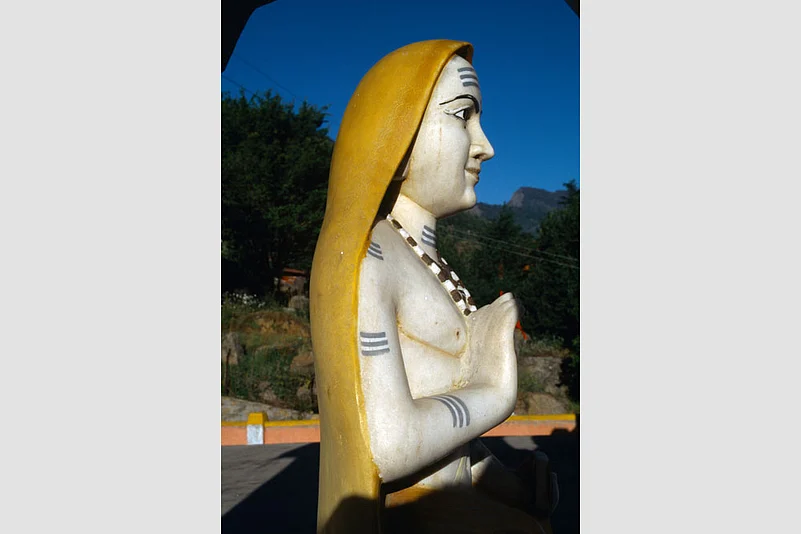

Although the varieties of Hinduism defy doctrinal unity, maya and Brahman are essential parts of a philosophical vision that many people now identify with the religion. In large part, we owe this vision to Adi Shankara, a religious thinker—perhaps the nearest that Hinduism might have to a theologian—who, roughly twelve hundred years ago, transformed Hindu beliefs and practices, established temples and schools across the subcontinent, and in many ways laid the foundations of modern Hinduism, which is now the third largest religion in the world.

In Europe, the eighth century was the era of Charlemagne’s bloody expansion of Christendom, through campaigns against the Saxons, Saracens, Moors and Slavs, and of his ascension to Rome’s Christian imperium. Shankara’s roughly contemporaneous efforts to establish a monastic order and assert his religious vision in India were vastly different: his was an intellectual struggle, prosecuted through debates across the subcontinent. At the heart of Shankara’s interpretation of Hinduism is an idea that remains as powerful as it is paradoxical—nirguna Brahman, a god without qualities.