The nine-year Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan (December 1979-February 1989) led to a multi-dimensional conflict and not merely, as this book’s title suggests, an Afghan-Soviet war. It was a ‘holy war’ against an occupying power and a Communist Afghan government perceived to be un-Islamic, if not anti-Islamic. It also became a decisive engagement of the Cold War. For Pakistan, which not only helped the Mujahideen, but was an active participant in a war that provided an opportunity to acquire benefits, but at long-term costs. Imrana Begum’s main interest is on this last aspect: the widespread and continuing consequences of the conflict on Pakistan. She covers them comprehensively and competently. She also dwells on developments in Afghanistan that led to the Soviet intervention.

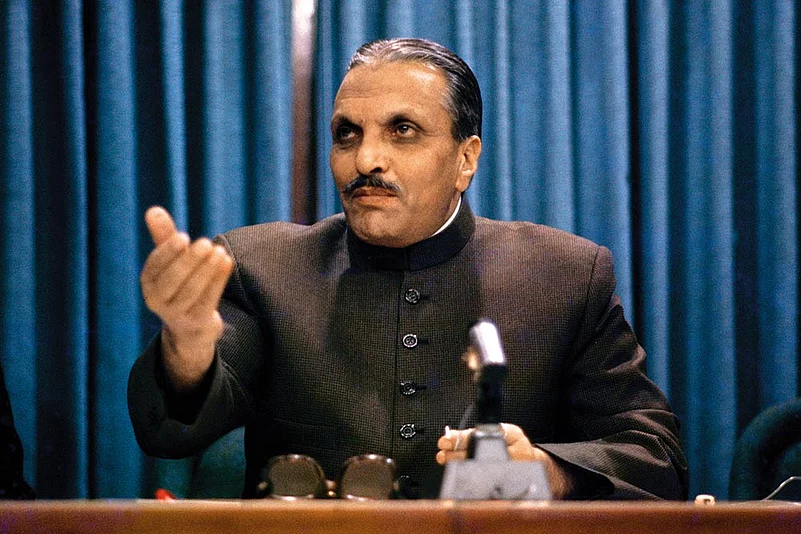

The Soviet move came at the fag end of a year (1979) that recast West Asia. It witnessed the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Saddam Hussein’s elevation to Iraq’s presidency, radical Islamists’ attack on Mecca’s Grand Mosque and Iranian students’ taking hostage 400 US embassy personnel in Tehran. In Pakistan, Gen Zia-ul-Haq executed former PM Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, despite international appeals.

While the Soviets were deeply concerned at the surge of Islamic extremism and its potential impact on the central Asian republics, it is an open question if the despatch of forces across the Amu Darya was a defensive move or part of Russia’s historic desire for access to warm waters. It surely was an attempt to stabilise the Communist regime in Kabul, whose communist agenda had provoked violent reactions and a movement of refugees into Pakistan.

Imrana Begum gives brief, accurate accounts of the immediate impact of the Soviet move. As the US, with Saudi and Chinese support, decided to give all-out assistance to the Mujahideen to combat Soviet and Afghan forces, Zia was transformed from a pariah to a hero and Pakistan became a frontline state. Consequently, it received large amounts of military and economic assistance. More importantly, Zia’s overthrow of democracy was forgiven, as was his decision to enforce a regressive Islamisation.

Imrana Begum obviously believes that Zia was responsible for taking Pakistan away from the path of moderation to that of fundamental Islam. Its effect was felt in the rise of sectarianism, with the unleashing of Shia-Sunni violence, ethnic fractures, fundamentalist agendas in education, criminal law and on gender issues. Imrana Begum notes, “Ever since the creation of Pakistan, a hotly debated topic was, and still remains, is whether Pakistan was meant to be an Islamic state or a secular state with a Muslim majority. While lip service was paid to Islam in all eras, it was Gen Zia who hoped to end this debate once and for all”.

As fundamentalism has crept into every crevice of Pakistani life, it is necessary for scholars like Imrana to examine if Zia was only a catalyst in hastening a process inherent at the core of the Pakistan project itself. The ‘lip service’ device was bound to fail. For, a country based on the two-nation theory would inevitably go in the direction of fundamentalist Islam.

Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme flowed from Bhutto’s decision after the 1971 decisive defeat. It had become clear to the international community in the 1970s that it was clandestinely pursuing that path. The US opposed Pakistan’s nuclear weapon ambitions and imposed sanctions, but with Pakistan playing the vital role of a regional ally, it turned a blind eye to it. With China assisting Pakistan’s programme, it is doubtful if the US could have effectively blocked Pakistani ambitions, but the Soviet military presence in Afghanistan stopped any moves towards it. It also foreclosed India’s options to take strong measures to prevent Pakistan from acquiring nuclear weapons. For India, this is the enduring legacy of the Soviet ingress into Afghanistan. Today, as China refrains from strangulating the North Korean regime, the US could well recall its own approaches towards the Pakistan programme.

Imrana Begum sheds light on some dark areas of Pakistan, which often escape attention, that exist as a result of the Soviet occupation of its neighbour. These are the rise in heroin trafficking and drug addiction among Pakistanis and the fillip to gun culture, with all its attendant political and social connotations. The impact of Afghan refugees on Pakistani society and economy has drawn greater attention, but Imrana Begum covers its various facets well.

All in all, this is a useful, if a bit dry, reference book on what Pakistan has become, and should find a place on a shelf of books on Pakistan.