If God had a face, what would it look like?

And would you want to see, if seeing meant that you would have to believe

In things like Heaven, and in Jesus and the saints, and all the prophets?

—From “One of Us”, sung by Joan Osborne in 1995 and written by Eric Bazillion

Times were troubled and then a pop song came along, posed this eternal question and gave no answers. If you believe in god, does it also mean you believe in saving god’s reputation? And would it mean blasphemy if you write about religions’ extremism? Organised religion has always represented unfreedom.

Times have always been troubled and today, censorship is normalised for religions’ sake. Books are banned, writers are under threat and mobs have unleased terror.

It is like feeding a black hole with bans, fatwas, killings. Nothing will ever be enough. It is an exercise in futility in the digital age. People will find what they want to read. Ideas, books and art are too powerful to be deterred by such arm-twisting methods. They might even bring in religion to justify their claim for censorship. They will bend it to suit their fragile egos. Dissent, the freedom to question, to disagree and to argue is an inalienable right. To write is to express.

Over the years, blasphemy has come to mean injuring god’s reputation by slandering. But do we kill and destroy to protect god’s reputation? Isn’t that a reductive idea of god?

Book bans have spanned centuries. Four hundred years ago, when Galileo espoused a heliocentric solar system, he was hounded by the Catholic Church which branded it as heresy.

In secular India, which first banned Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988, who is a heretic or a blasphemer and who deserves the right to be silenced, even sentenced or punished? Is there no scope for dissidence, disagreement? Aren’t we supposed to be alive to possibilities? It’s sad that fear and self-censorship are in abundance in the media, publishing world too.

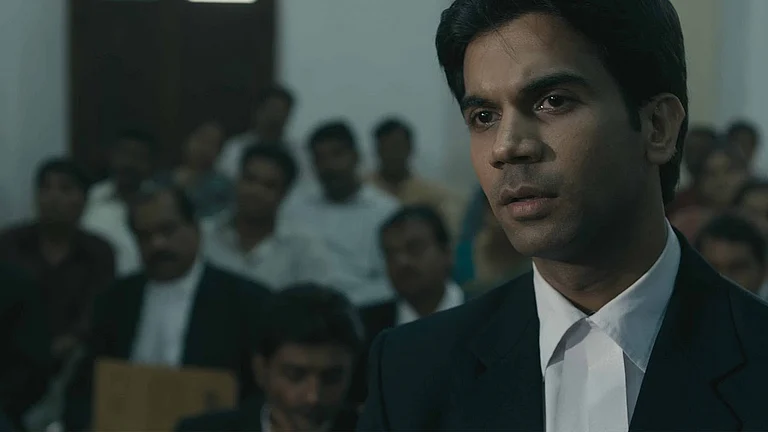

Courts are empowered to resolve the burden of offence in contentious cases, including those involving blasphemy.

In an FIR regime where cases against such ‘offences’ are rampant, how does one exercise the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression? Yes, there are “reasonable restrictions” that include considerations of state security, decency and public order. But the constant evocation of laws that deter expression, which might be interpreted as insulting to religion, is increasing.

We can always agree to disagree. We must reserve the right to question. We must rest our cases on evidence, rather than on flimsy grounds of offence. And nobody has the right to not be offended.

ALSO READ: Salman Rushdie And The Iran Fatwa

“If you don’t like a book, read another one. If you start reading a book and you decide you don’t like it, nobody is telling you to finish it. To read a 600-page novel and then say that it has deeply offended you: well, you have done a lot of work to be offended,” Rushdie said.

It makes absolute sense. You don’t have to jail or kill a writer for offending you.

These are dark times. The age of unreason. But hope is our ultimate defence. Stories will live on. They don’t die. Like questions.

You can continue to be offended. Even the weather can offend someone. Who do you punish for that?

“What if God was one of us?

Just a slob like one of us

Just a stranger on the bus

Tryin’ to make his way home?”

That’s how the song goes. Is that blasphemy? To imagine god as one of us.