Few would know that the landscape genre in India came into its own only by the end of the nineteenth century, when artists trained at art schools and equipped with portable art material began to step out of their studios to paint from life. There was an outpouring of landscapes not just from the metropolitan centres but also from smaller towns like Kolhapur. In industrially developed art material like Winsor and Newton pigments and Whatman paper, which could take many colour washes without disintegrating, artists found a new method of experimentation which would allow them to make an effusion of forms, splitting colour beyond the drawn image and an erasure of compositional clarity. Not only did this set about a new adventure in landscapes, but allowed for a reclamation of memory and lost territory.

In the book published by the Delhi Art Gallery, a comprehensive overview is obtained of the genre as it transmutes into modernist abstractions and to the later experimental works in new media. The art scholar Shukla Sawant points out in an essay that the picturesque views of the Company Period painters, like the Daniell brothers and William Hodges, were also a means of colonial mapping where optical devices such as the telescope were utilised to expand their visual comprehension of territory. Conversely, this very training in and exposure to perspectival ordering would result, about 200 years later, in artists who began to create counter-hegemonic visual negotiations of colonial mapping “to relook at their own land”.

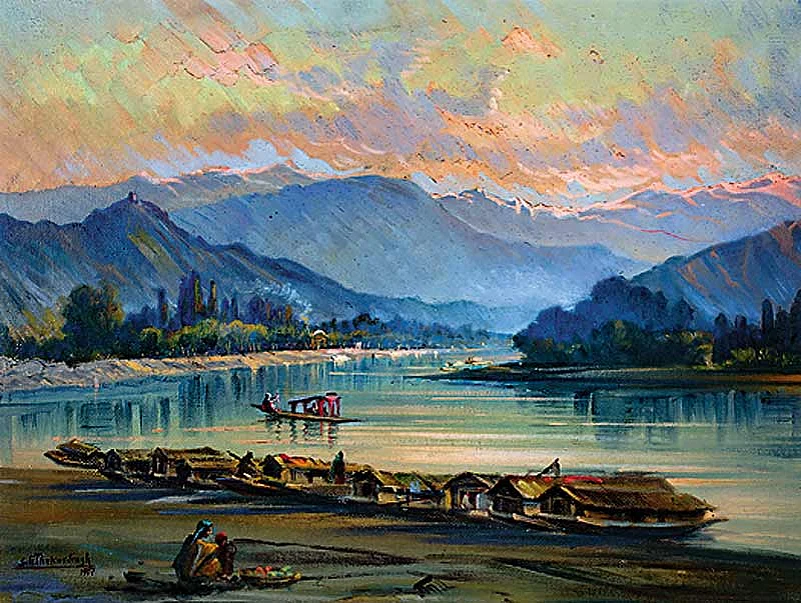

A slew of artists come to light whose works reflect the environment with intimacy. These highlight the new excavations of heritage sites, cities with their trams and traffic and stretches of land without trees or shrubbery. S.L. Haldankar, for example, not only set up his own art studio for ‘true-to-life portraits’ in Bombay, but also played with the fluid contours of the landscape to feature regional geography and grapple with notions of identity. In revelatory works such as those of M.K. Parandekar, panoramic views included, for instance, the ghats of Nasik and the mountainscapes of Mahabaleshwar. The bazaars of Lucknow, the ghats of Varanasi or the fishing harbour near Alibagh become grist to the painterly mill in the works of artists like Prema Pathare. Most interestingly, L.N. Taskar’s beige-coloured middle ground paintings highlight the subject, such as a frontal nine-yard sari-clad woman actively engaging with the viewer, instead of in a passive subordinate position.

The captivating landscapes of the ’30s and ’40s form the sinews of the book as artist after unknown artist reveals his dexterity with perspectival space and contour formation. The works are also a documentation of the period where many of the sites have become ruins or disappeared over time. In eastern India, the shifting modes of rural life become visible in the works of artists like Haren Das and his quiet reflections of the changing countryside. With artists like Radha Charan Bagchi, water is frequently used as a mirroring device, as Sawant points out, “doubling possessions and expanding the symbolic presence of temples and palaces—a fluid set of meanings associated with possession and their eventual dissolution”. When Bagchi in a woodcut portrays a family in transit in Calcutta, wading through knee-deep water towards the ferry, it projects an oblique trajectory from that of the excitement of industry and technology. The wide boulevards and affluent lifestyles transformed into light-bedecked spaces in the etchings of Ramendranath Chakravorty reflect the new Calcutta, while the waterfront portraits of Bijayan Chakravarti and Chittoprosad are reminders of its underbelly.

The heydey of landscapes is the 19th century, as critic Kishore Singh points out, which wanes in the 20th. The transmutations into dreamy, yet real landscapes of Rabindranath Tagore are well known, as are Benode Behari Mukherjee’s memory of rocks and trees stretching for miles. The doyens of modernism, like Souza, Husain, Raza, Ram Kumar, Akbar Padamsee and even Gade, create abstractions in impasto, which mark territory within the artistic space. Later painters like Sudhir Patwardhan, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Ramachandran and Manu Parekh delve into the evolving genre, etching cities which particularise a universal humanism.

This handsomely produced volume also has a tabulated historiography of landscapes. In this fascinating overview, a neglected genre comes into its own, offering a counterpoint—a humanly gained one—to today’s digital mappings.