“Some copies of the book reached the Indian bookstores and Muslims here began to agitate. Buta Singh rang me up and told me to check whether we could ban the book in India. I told him that if a copy of the book is provided to me, I could have the matter examined. It took me two days to read it. I read The Satanic Verses and came to the conclusion that the book needs to be banned in the interest of maintaining law and order in the country.”—from The Honest Always Stand Alone

by former home secretary C.G. Somaiah

who served under Buta Singh

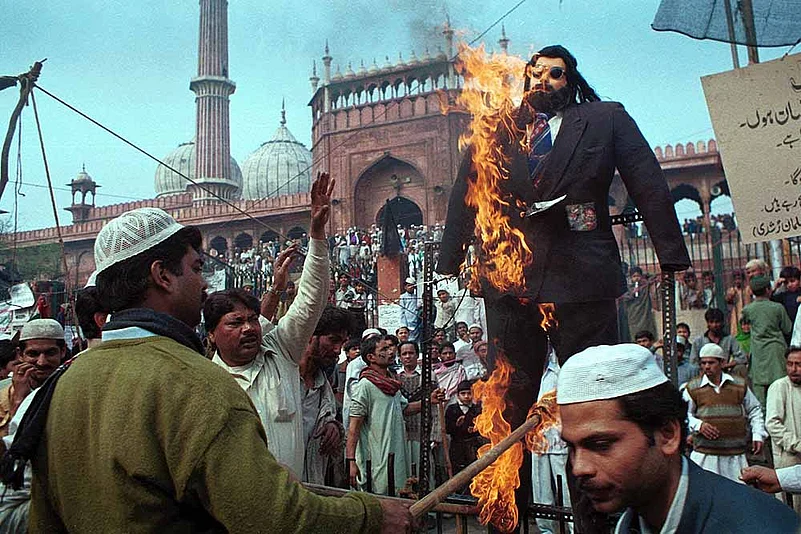

Where they ban books, they might also drive out people some day. Twenty-five years ago to the week, the Indian government banned The Satanic Verses. Salman Rushdie’s controversial book was driven underground and remains buried till now. Indeed, few books have raised the emotional pitch quite as high as this one. In some ways, the ban set off a precedent for other books that were swept off bookstores—all penalised for being controversial, provocative, inflammatory, or worse, blasphemous.

But how are books banned in India? And, once banned, can’t anyone ever un-ban them? Officials in the Union ministry of home affairs, under whose decisions lie the fate of books, shrug the questions off with a vigorous shake of heads. “We don’t ban books,” they say. So who does? Controversial books have met with various responses here. Sometimes, pressure is brought upon the publisher to withdraw books from circulation. Like it was with A.K. Ramanujan’s Three Hundred Ramayanas, which was banned from the Delhi University curriculum after being attacked by vitriolic right-wing groups. Oxford University Press, its publisher, bowed to their demand.

Other victims of bans include Dalit writer Senthil Mallar, who dared to rewrite the history of the Tamils and faced a vicious tirade for his pains; James Laine’s Shivaji, which was banned by the Maharashtra government; and The Life of Sri Aurobindo by Peter Heehs.

***

Three Disappearances

| The Satanic Verses Banned: October 1988 Why: After a controversy in Islamic countries, which deemed it blasphemous, India banned the book | Shivaji Banned: January 2004 Why: After the Shiv Sena went on a rampage saying it lampooned Shivaji, Maharashtra banned the biography | The lives of sri Aurobindo Banned: November 2008 Why: The Orissa HC passed a temporary injunction after protests by irate Aurobindo followers |

***

The banned books remain out of sight still—the home ministry (MHA) says it doesn’t get requests for lifting bans. To understand the process of banning books, Outlook filed a request for information through RTI on January 11, 2012. After a year and two appeals to the Central Information Commission, the home ministry responded by saying that information could be provided only for three books: The Satanic Verses, Shivaji, the Hindu King In Islamic India and Aurobindo. Further, they said inspection of some files as mandated under RTI was not possible as they contained inputs from the Intelligence Bureau (which is exempt from RTI.) The Information Commission responded by directing the home ministry to make the files available after applying section 10 of the RTI Act, which allows for hiding inputs from intelligence bodies.

The ban on the The Satanic Verses was initiated by the Centre. The department of revenue of the Union ministry of finance, through a notification dated October 5, 1988, banned the book under the Customs Act, 1952. The next day, a copy was forwarded to all chief secretaries/home secretaries/DGPs and IGPs of all states and UTs. Then, a few days later, The Satanic Verses was banned throughout India—the first country to do so. According to the ministry, New Delhi wanted ‘every copy of the book, pamphlet and document containing the objectionable matter, material, reprints and translation or extracts therefrom’ to be forfeited and necessary action taken if they were found in circulation. No one knows how many copies were impounded and destroyed. After all the brouhaha over the book, there was the plot device even Rushdie couldn’t have matched. A home ministry note says, “This is to inform that our ban is only for purpose of import.”

The story of the ban of Shivaji, the Hindu King in an Islamic Country, by James Laine, unfolds differently. In July 2003, OUP released 803 copies of the book. Over 200 copies were sold in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Karnataka. Soon after, the publisher received objections from historians, who suggested the publisher retract objectionable portions. Right-wing mobs went on the rampage in Pune, and the book was banned.

When asked why, the home ministry’s response to Outlook’s RTI ran like this: “The MHA is not in the picture, as whatever has been done has been done by the government of Maharashtra. The decision to ban the book was taken by the Maharashtra cabinet on January 14, 2004, which lodged an FIR against the writer, publisher and printer.” A scrutiny of the documents supplied under RTI shows how pressure was built up to ban the book despite an assurance by OUP on November 21, 2003 that they were withdrawing the book with immediate effect.

A letter dated January 9, 2004, from the Maharashtra Information Centre to MHA, asks if the book by James Lane (sic), in which some derogatory remarks were made against Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, has been banned. The MHA on February 3, 2004, wrote to the Maharashtra home secretary: “The book reportedly contains derogatory remarks against Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. You are requested to look into the matter and take appropriate action under the law. An action taken report in the matter is also solicited.”

Pune’s Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute vandalised by protesters in 2004

In 2010, the Supreme Court lifted the ban on Laine’s book, but with a caveat: the author was requested to delete some lines. The lines were the following: “The repressed awareness that Shivaji had an absentee father is also revealed by the fact that Maharashtrians tell jokes naughtily suggesting that his guardian, Dadaji Konddev, was his biological father.” Laine, professor of Religious Studies at Macalester College in the US, says, “I responded to the Supreme Court of India that I was unwilling to edit my book in the way suggested. My point was that if writers are asked to change their books simply because someone finds them offensive, there will be a chilling effect on freedom of expression.” Laine says he was flabbergasted by the whole affair. “It was a scholarly book and I expected only a few scholars to consult the work. I had no idea it would catch the attention of people who were more interested in the politics of representing Shivaji Maharaj, than in the scholarly investigation of his biography.” Despite no ban, Shivaji has disappeared from bookshops.

The banishment of Peter Heehs’s The Life of Sri Aurobindo began on November 4, 2008, when the Orissa High Court ordered a temporary injunction on the book’s sale after a group of Sri Aurobindo devotees said it denigrated the spiritual leader. By December 12, the MHA was seeking the advice of the Union ministry of law and justice to find out “who was the competent authority to restrain the publisher from publishing The Life of Sri Aurobindo”. In true bureaucratic spirit, the law ministry delivered a perfect rebound, saying that any such decision was to be taken by the home ministry itself. Those against Heehs’s book petitioned the MHA, asking for a ban. This is what the MHA’s internal security note had to say on the matter: “This file related to a book, The lives of Sri Aurobindo by Peter Heehs, with a clear agenda of misrepresenting the life of Sri Aurobindo and belittling the achievements of a national hero and freedom fighter and hurting the sentiments of millions of his admirers and devotees in India.”

Though the MHA says it cannot take a decision on a book without reading the contents, it was curiously silent on the matter in deference to the Orissa HC. The Life of Sri Aurobindo remained temporarily banned under the 2008 injunction order of the HC. The injunction spoke only about publication—its printing in India. Its import and circulation have never proscribed. Strangely, the temporary injunction was never lifted, and the book disappeared from Indian stores. “The more people read the book, the more it will become clear that far from ‘denigrating’ Sri Aurobindo, it actually brings out his many-sided genius,” Heehs tells Outlook.

From the response to the RTI, it seems that banning a book follows no regular pattern. The reasons for banning are couched in vagueness—books can be struck down for offences ranging from blasphemy to defamation. It is instructive to look at the obfuscation surrounding the ban of The Polyster Prince, written by Hamish Mcdonald. Criticism of Dhirubhai Ambani and references to Pranab Mukherjee, then a minister, were enough for the then-united Reliance family to obtain a restraining order from the court, with a further threat that they would approach every court in the country. The book duly vanished. The MHA, strangely, says it does not have information on the ban on The Polyester Prince.

When ban orders don’t flow clearly from the Centre, as they most often don’t, back-and-forth opacity and silences throttle a book. Beyond the public abuse hurled at a book, the reading public is kept in the dark.