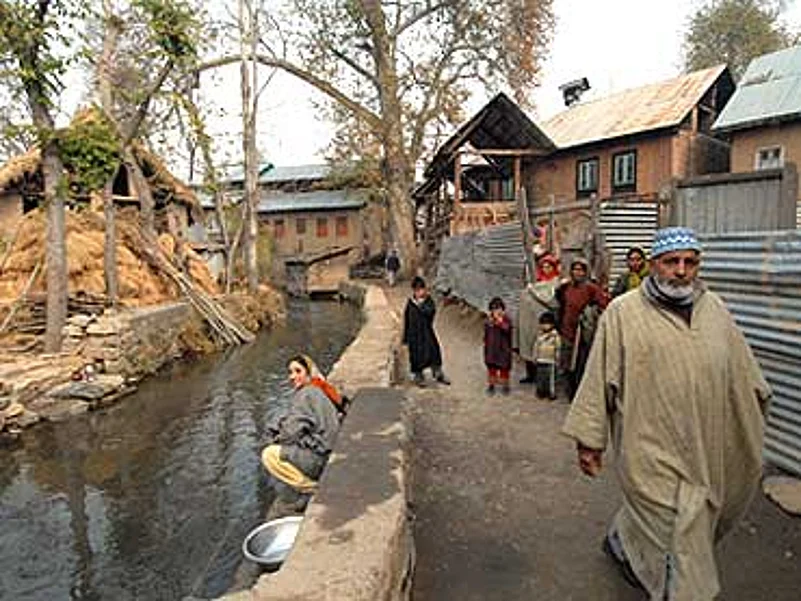

Still waters: The old mohallah and the brook behind Basharat’s house

"In those days there were no cars and buses and no tunnel in Banihal," Amjad uncle would say. The Kashmiri labourers would walk back home to the Valley all the way from the towns and cities of Punjab. "When they'd reach Banihal and see the headgear of a Kashmiri woman in the distance, they would shout, 'We are home!'"

This story, heard in the peaceful early eighties, made little sense to me, because my life revolved around my village, Seer, in a southern corner of Anantnag district. I rarely left the village, except for occasional visits to Anantnag or Srinagar. In summers, I would help grandfather and other men carry sacks of seedlings from the nurseries. Women would bend in rows in the well-watered fields, singing as they planted. Grains were stored in wooden barns, and haystacks rose like mini-mountains in the threshing fields, around which the children played hide and seek. By autumn, the apples in our orchards would be ready to be plucked, graded, packed into boxes of thin willow planks, and sold to an apple merchant. Village children were adept at stealing apples, so my brother and I would take turns as lookouts after school. In winters, my friends and I would spend afternoons sliding down the snowy slope of the village hill or playing cricket on the frozen waters of a pond nearby, and our evenings bent over our books in the yellow light of kerosene lamps.

When I went away even for a day, on my return I would be impatient for the sighting of a familiar landmark—an old wooden hut on the slope of a hill that towered over my village. The bus would follow the black ribbon-like road dividing vast expanses of paddy and mustard fields. A few of the mud and brick houses along the road were brightly painted, but most were naked brick; dust and time had coloured their rough timber windows and doors a deep brown. Every third house, a ground-level room had been converted into a shop. The bus would slowly come to a halt in the village square, not far from a blue-and-green milestone that read: 'Seer, 0 Km'.

I would smile at the old hut on the mountain, greet the neighbourhood men who regularly sat at the wooden shopfronts to gossip, talk politics and cricket. It was home. I would measure the distances from our blue-and-green milestone: Srinagar was 57 kilometres; Jammu was 243 kilometres. Delhi was very far. And New York existed in comics and 'general knowledge' books.

Alight here: The main thoroughfare at the Seer Hamdan village

The winter of 1990 brought war to Kashmir, and to my village: gunbattles, crackdowns, arrests, torture. And cricket players leaving for Muzaffarabad to train as militants. I added another measure of distance: Muzaffarabad, 232 kilometres. And then after much violence, as worried parents sent me and my generation of boys to schools and colleges in Delhi, Aligarh, Bangalore, we measured new distances.

For many years, I continued to measure the world from my village milestone. But slowly the milestones began to change. In my mid-twenties, as I began travelling home from Delhi as a journalist, I understood the story Amjad uncle would tell us about the Kashmiri workers exultantly shouting "We are home!" at their first sight of the distinctive headgear of a Kashmiri woman. Kashmir had become the text and subtext of my professional, personal and social worlds in Delhi and elsewhere. Being away had changed the marker of home from the old hut on the hill to the first sight of the mountains circling the Valley as the pilot announced, "We are about to land in Srinagar." The native place had expanded to include every bunkered and broken street in Kashmir.

I had moved farther and farther—from Delhi to New York, spending most of my time writing and learning to write, a process that was difficult to explain to the men who spent their days sitting at the shopfronts in my village. Yet a few weeks after publishing my first book, I returned to my old home and spent a day hanging out with them. Amjad uncle was dead and his eldest son occupied his place; Khalid, a childhood friend, had become a doctor, and another friend, Manzoor, was a paramedic in the local hospital, treating people in the same building in which he had been interrogated and tortured during a crackdown in the early nineties. Shafi, the fast bowler of the village team, who became a militant and was maimed when a hand grenade exploded in his house, limped past the old pharmacy, where Amin still stacked boxes of Crocin and Paracetamol.

But a lot of younger people had left, like me, to build new lives in various cities of the world. A few army vehicles patrolled the village market. As I sat with old neighbours on Amjad uncle's shopfront, and we told and retold the old stories, the worries, the temptations and the frictions of my multiple lives in often colliding worlds disappeared. I thought back to the time when I had left my village for the first time as a teenager, carrying a VIP briefcase. I did not know then that I would never really come back home. I am leaving again, knowing that my arrivals and departures will continue, that I will carry my home with me through airports and avenues and offices across continents, taking it along with me to the world beyond its doors.