In Churning the Earth: the Making of Global India, economist Aseem Shrivastava and ecologist Ashish Kothari interrogate what is unarguably the question of greatest consequence for our times: does contemporary globalisation, as a “definitive prescription not just for a certain arrangement of economic affairs, but for a way of life”, offer solutions to the impoverishment of billions of people, and for unborn generations and non-human species?

This immensely significant and compelling book—one of the most important in recent years—maps painstakingly the political economy of both the socio-economic consequences and environmental impacts of the current growth path. The picture emerging from this densely argued treatise is bleak and harrowing—a picture of greed, inequality, suffering, and the reckless, irresponsible destruction of the planet’s resources.

The authors worry also about the values at stake in the path of growth embraced by the Indian elite, of competiveness, aggression and covetousness, which have pushed other values—cooperation, compassion, integrity, frugality, simplicity, responsibility, equity and loyalty, to the background. They make no attempt to hide their indignation, but this never compromises their extraordinary scholarship and rigour and their magisterial mastery of facts. The tone is measured and reasoned, not shrill or accusatory, even as they demolish, one by one, almost all the claims of neo-liberal economists and planners.

The carefully marshalled facts are lit by passages of lyricism. Speaking of farmers’ suicides, for instance, they note that “the days when India used to live in its villages are over. Now it dies in them”. They speak of the new “architecture of fear” of cities which are “ready to take off from the stench of neighbouring slums, and fly into a globalised stratosphere”. There is the searing anatomy of inequality and its consequences. We learn, for example, that the footprint of the wealthiest Indians is 330 times that of the poorest 40 per cent; and that with each new SEZ, we lose the capacity to feed 50,000 to 1,00,000 people each year.

The authors explain that global economic integration has proceeded most rapidly in financial markets, leading to “gambling on everything—from currencies, companies and real estate to natural disasters and pension funds”, turning “capitalism into what traditional economic wisdom used to fear: a casino”. Capital markets reign, rather than physical capital being available for investment in manufacturing and production.

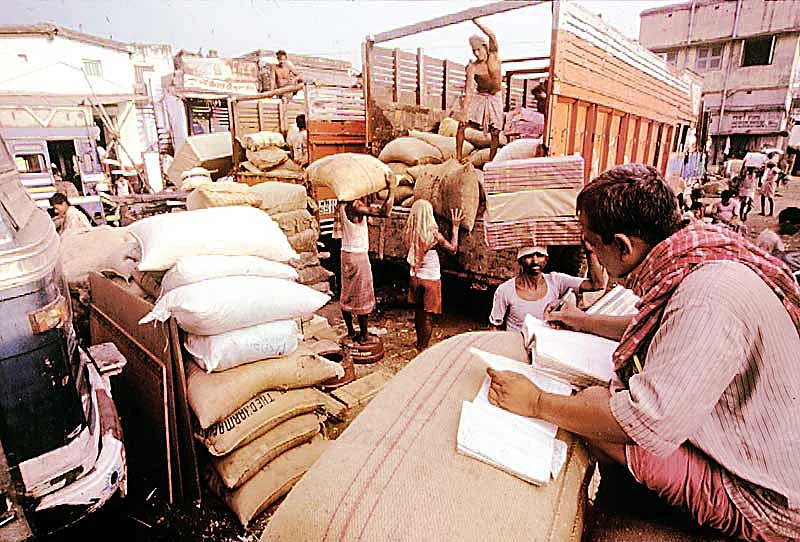

We are told that market-led growth will create more wealth and jobs. Contrarily, the book describes the striking phenomenon of “jobless—even job-destroying—growth”. The foremost goal of business is profits, not jobs, and the authors establish that the period of rapid growth has led to significant reduction in jobs in the formal sector. They quote Joan Robinson: “The only thing worse than being exploited by a capitalist is to be exploited by no one at all”. This is the result of a combination of mechanisation and automation, and increasing outsourcing of production and services to the unprotected informal and cottage sector, characterised by dirt-low wages, child work, and no labour protection. They underline that the unorganised sector produces half the country’s output, employing nine out of ten Indians.

The authors clarify that they are not against mining and large industry, but believe that we need to reflect soberly on “to what extent, for what purpose and under what conditions” should these be fostered. They oppose global capitalism, but not authentic globalisation “in the sense of a mature cultural understanding amongst various peoples, which would render the arms industry obsolete and allow free movement of people across borders”. They do not advocate state socialism, which “paves the way to ecological dystopia no less than the paradise dreamt by enthusiastic neo-liberals”.

Shrivastava and Kothari’s counsel needs to be heard in South Block and Yojana Bhavan, where it should be made compulsory reading. We must heed their overwhelming evidence that the Indian economy “may be in good statistical health”, but “it is by no means in good social or ecological health”. The authors advocate an alternative “radical ecological democracy”, which offers citizens the right to participate in all decisions affecting their lives, hoping that they will pursue wiser pathways of human equity and ecological sustainability. As the authors conclude: not just is another world is possible, “it is long overdue, if the world is to survive at all”.