Who owns India? Who owns the forests and rivers, the farmlands eyed by industry, the slums coveted by real estate developers and airport authorities, the hills and plateaus desired by mining barons? In roughly a third of the country, this is no idle question. Citizens, governments and corporations are negotiating, sometimes violently, over the answer. The country’s tribal belt, which stretches across the eastern and central parts of the country, is where many of these conflicts are unfolding. The people who live in these areas are poor but the natural resources are rich—tempting to corporations and the government.

The nationalists of the 20th century had a simple answer to who owned the land: Indians did. The British did not. But when the nationalists assembled the jigsaw puzzle of diversities to define the Indian nation, some pieces got left out of consideration. Among those were the original tribal inhabitants of the country, who are now called adivasis. One experience many adivasis share is the overriding of their rights in the name of development and in the interests of other Indians. “It’s as if middle and upper classes and castes have seceded into outer space,” the writer and political activist Arundhati Roy says. “They look down and say, ‘What’s our bauxite doing in their mountains, what’s our water doing in their rivers?’”

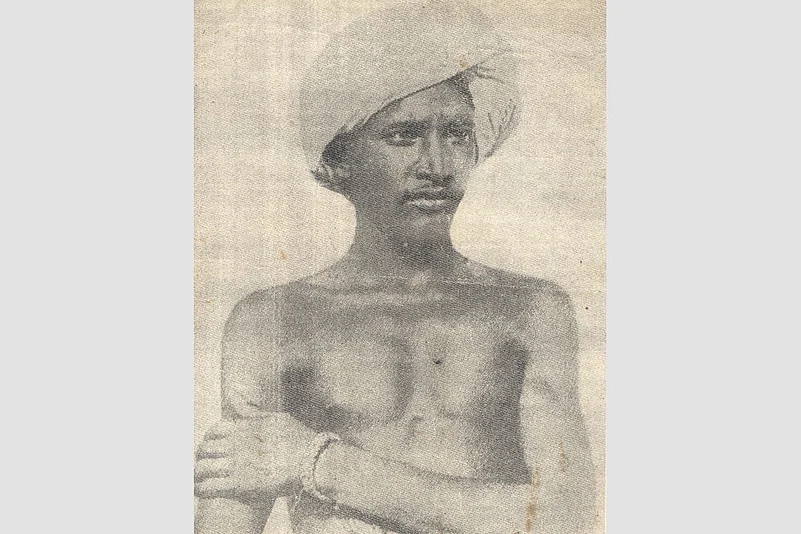

Although adivasi efforts to defend their lands date back centuries, accounts of many of those struggles are lost to history. The life of one 19th century rebel, Birsa Munda, is an exception. Born in 1875 in Chotanagpur, in what is now the eastern state of Jharkhand, and raised in a bamboo hut, the young Birsa herded sheep, played the flute and learned the medicinal power of local plants. In adulthood, he was known as a healer, and ultimately as a defender of his people against the British, their Indian middlemen and Christian missionaries. His was a firework of a life—he was dead by the age of 25—but the embers of his struggle still burn.