“MOM never disappoints”, was how Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulated the scientists of the Indian Space Research Organisation at the successful insertion of the maiden Mars Orbit Mission (MOM) into the Martian orbit. September 24, 2014, at 07.47 IST, the spacecraft Mangalyaan started orbiting the Red Planet and 12 minutes later, the signal was received at the Mission Control Centre.

It was indeed a remarkable achievement by any standard. With this success, India joined an elite club of three—Russia, the US and the European Space Agency—to have put a spacecraft into the Martian orbit. Noteworthily, it has been able to do it in its first attempt and at a fraction of the cost of missions by other nations. The total cost was about Rs 450 crore (US $75 million).

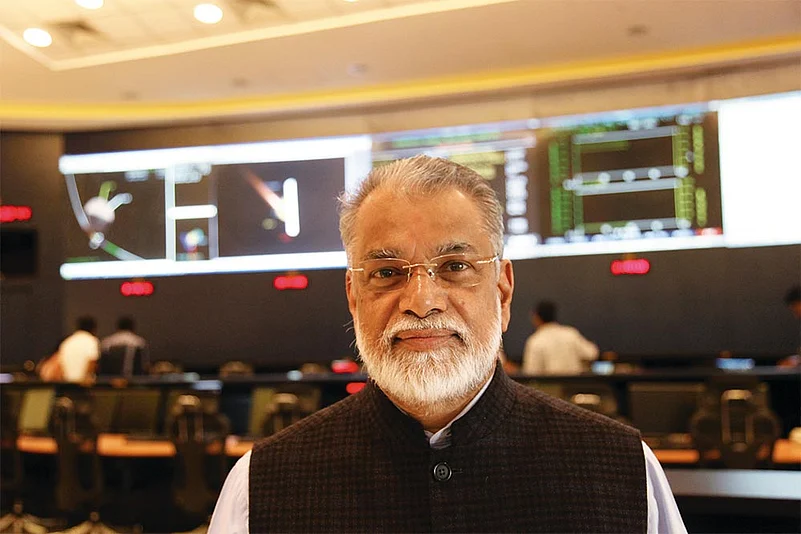

The ‘Man behind the Mangalyaan Mission’ was ISRO chairman Dr. K. Radhakrishnan. An engineer and a management graduate, he has been a career ISRO man. Joining as a technical assistant-c in 1971, he rose through the ranks and its various centres to become its head in 2009. Thus, one hoped that his memoirs would give us a unique insight into the workings of this behemoth and also put it into a broader perspective. The book is somewhat disappointing in these respects.

India’s space programme has come a long way from the setting up of Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) in 1962 under the chairmanship of Vikram Sarabhai. Just as India’s atomic energy programme got to be identified with Homi Bhabha, Sarabhai’s name was synonymous with space research. In 1969, ISRO was founded and INCOSPAR disbanded.

The rationale for spending precious resources on space research was questioned by many. These were, after all, the times when we were living from ‘ship-to-mouth’. However, Sarabhai was in no doubt about the importance of the programme in nation building. As he said in 1969, “We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society.”

From modest beginnings of launching sounding rockets from Thumba to the massive infrastructure that exists today, ISRO has come a long way. With a budget of about Rs 7,500 crore and employing about 18,000 people directly, ISRO has fabricated satellites, developed launch vehicles and even launched Chandrayaan, a successful unmanned mission to the moon. It is developing the expertise for a moon landing as well as a human spaceflight programme, though that is still sometime in the future.

The book begins with the retirement of Dr. Radhakrishnan and his reminiscing about his life with his colleagues. Born in a middle-class family in Kerala, he graduated in electrical engineering from the Government Engineering College, Thrissur, before joining ISRO. Subsequently, he also did a PGPM from IIM Bangalore and a PhD in management from IIT Kharagpur. He has been closely associated with various units of ISRO throughout his long career, including its largest centre, the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre and the National Remote Sensing Agency.

The author interweaves his personal life (including his passion for Carnatic vocal music and Kathakali) well with the narration of events in his professional life. And sometimes, in a wonderfully understated way, he gives us a glimpse into the human being behind the successful technocrat. Thus, for instance, he talks about how he and his wife faced up to the fact that they could not have children. Or when, on losing out on some promotion in the organisation, “felt abandoned and clearly side-lined” and how the “solitude of the guest house at Kharagpur allowed me to cry like a baby”. However, at other times, trivial details tend to be annoying, like his wearing a “Louis Philippe blue formal shirt and a pair of navy blue formal trousers” on his first day as ISRO chief. Alliterative chapter titles also seem a bit contrived.

Given the size of ISRO and the inherently collaborative nature of space exploration, where large teams of specialists from diverse fields need to work together and cooperate, it is to the credit of Dr Radhakrishnan that he highlights team work. However, his penchant for naming a large number of individuals that he worked with throughout his long career can get a bit tiresome, especially because these names make no sense to the reader.

The successful fabrication of the first Indian satellite, Aryabhatta, in 1975 launched India into a select club of nations with indigenous satellites. India now has one of the largest satellite networks for a variety of purposes. Satellites need launch vehicles and it is here that ISRO’s report card is mixed. Though the first Satellite Launch Vehicle (SLV) was successfully launched in 1979, it was with the development and deployment of the PSLV in 1993 that the programme really took off. PSLV remains the most successful launch vehicle developed by ISRO.

However, PSLV does not have the capability to launch heavier satellites, thereby severely restricting the scope of its use. For launching heavy payloads into space (like, for instance the INSAT series satellites, which weigh around 2,000-2,500 kg), a much more powerful vehicle is required and this was what led to the start of the GSLV programme. For this purpose, the crucial piece of technology was the cryogenic engine, which is added as a third stage to the existing components from the PSLV.

The cryogenic engine and its related technological infrastructure were to be initially supplied by the Russians and thereafter developed indigenously with the transfer of technology. In 1992, the US threatened to impose sanctions on both the Russian agency Glavkosmos and ISRO for violating the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) if the technology was sold to India. Though ostensibly the reason for the sanctions was the dual-use nature of the technology (in satellite launch vehicles as well as missiles), there was undoubtedly a commercial angle to the threat. The satellite launch business is very lucrative and the US did not want another competitor.

The threat resulted in the Russians reneging on the transfer of technology, but agreeing to sell seven engines instead. These were used by ISRO in a series of tests, while simultaneously attempting to develop in-house capabilities to design and manufacture the crucial cryogenic engine. After a series of failures, it was only in January 2014 that the first indigenously produced GSLV was successfully launched.

The whole saga of the development of GSLV, including its many failures and the final successful launch, are described well in the book. However, what is missing is any discussion on the dual-use nature of rocket technology. Despite public rhetoric about peaceful use of space technology, there never was any doubt about this in the mind of the planners or administrators. Throughout the ’70s and the ’80s, synergy between civilian and military applications was encouraged. In fact, the doyen of Indian space research, Prof. Satish Dhawan, admitted as much when he said, “Like nuclear energy, we could cross the divide whenever we wanted”. With the crossing of the nuclear rubicon, development of nuclear capable ballistic missiles became essential. The need for cryogenic technology to launch long-range missiles fit neatly into the indigenous development of the cryogenic engine for the GSLV.

Not surprisingly, the book provides a suitably sanitised view of the working of this large organisation which has never been open to scrutiny. However, as expected from a career ISRO person, the author steers away from any controversies. Thus, for instance, there is no detailed discussion of the controversial Antrix-Dewas deal in which his predecessor has been recently chargesheeted by the CBI. Or of ISRO’s not-so-stellar record in the widespread dissemination of technology. Sending a successful mission to Mars is obviously something to be proud of. However, the gap between running a dedicated, focussed technological mission and improving the general level of manufacturing competence and quality is huge.

As before every launch, just before the launch of MOM, the ISRO chief performed a pooja at Tirupati. The irony of the head of one of the largest scientific establishments in the country publicly seeking blessings in a temple for the success of a path-breaking scientific endeavour seems to escape us. But then, we are like that only.