He began chain-smoking as a third-grade student. In 1961, when he was a prominent member of the Communist Party in Siliguri, he had to appear before a general body meeting of the local party unit to face charges of public drunkenness. A year later, he fought an Assembly by-election on a CPI ticket only to lose badly, polling just about 3,500 votes. And in 1964, coming out of a group meeting at a party comrade’s house in Darjeeling, he collapsed, complaining of severe chest pain.

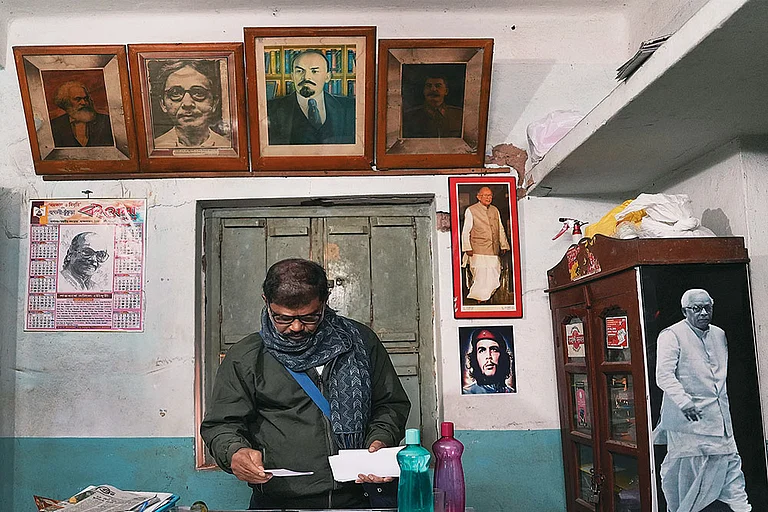

Recuperating from the heart attack, he would go to a neighbour’s in the evening to listen to Beijing Radio since he didn’t have a radio at home. He was deeply impressed by Mao Zedong’s tactical approach in organizing the Chinese revolution and wanted to replicate it in India. Better educated and more refined communist ideologues in Calcutta dismissed the mofussil man as ‘raving mad’. However, Charu Majumdar is considered one of the main theorists who sought to challenge the system of parliamentary democracy in India by organizing an armed struggle along Maoist lines. In the political history of India in the 20th century, the ‘mad man from Siliguri’ occupies quite some space.

The young communist, who was a lightweight in the party hierarchy, somehow had an insight into the groundswell of anger waiting to explode. Was he closer to reality than the more indoctrinated comrades in Calcutta? Some of them had been groomed by the finest British institutions. Racking his brains to analyse the Indian situation in the wake of the 1965 Indo-Pak War and an acute food crisis, he came up with a theory of armed revolution having a sharp focus on the agrarian sector. His argument—that the marginal or landless farmworkers and not the industrial workforce should be the vanguard of this revolution—was a pointer to his ideological affinity to China.

His distrust of the established communist leadership for being ‘revisionist’ led him to think of a practical revolutionary programme. Borrowing heavily from Mao, he started drafting a series of theses from January 1965 onwards.

Soon after the first United Front government came to power in March 1967, a group of young communists—still technically CPI(M) members—in the Himalayan foothills near Siliguri, led a sharecroppers’ rebellion against big farmers to take possession of farmlands, claiming the right to harvest. Initially, in Maniram panchayat in the Naxalbari area, around 150 farmworkers backed by the radical activists took away the entire standing crop. Inspired by Charu Majumdar’s iconoclastic theory of a peasant revolt, they decided to take charge of the affairs of field and farming. ‘From tomorrow onwards the system of landlordship is over in this area,’ Kanu Sanyal roared at a farmworkers’ conference on 7 May at Buraganj. ‘Farm fields will be demarcated from now on with the ploughshare and red flags and redistributed by the peasants’ collective.’

A peasant uprising began to sweep through Kharibari, Naxalbari and Phansidewa from the next day onwards. While militant farmhands captured tracts of cropland, and asserted their right to harvest, the big and not-so-big landlords fled the area feeling insecure. This trouble spot is of tremendous strategic importance, hemmed in as it is by Nepal, Bangladesh and the mountain ranges of Sikkim. Beyond those snow-capped mountains is China, actually Chinese-occupied Tibet.

The Calcutta newspapers ran lead stories about the unprecedented peasant revolt. Charu Majumdar, Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal—the heroes of the Naxalbari uprising—became household names overnight. The campaign to capture big landlords’ excess lands went on for another week. Threatened by the rebels, the big farmers turned to the authorities to give them protection. Facing minimal resistance, militant sharecroppers led by communist firebrands raided landlords’ houses, looted barns and seized guns. At a few places, radicals gathered outside a landlord’s house and called him out to surrender his gun. The big farmers, who had so long decided the fate of the peasantry, now meekly obeyed. The students at North Bengal University backed the militant peasants, and often gave them shelter on campus.

A little sarcastic about the CPI(M)-led United Front government, Majumdar, according to his colleague and biographer Souren Basu, said to a group of old party workers, ‘Your leaders opted for tasting power, and here people have snapped out of the trappings of parliamentary democracy to capture the state.’ Indeed the significance of fields of standing crops being taken over by indigent farmhands was not lost on the political analysts. The fact that their boundaries were demarcated by little red flags added to the discomfort of the authorities. In clashes that followed, tribal men and women retaliated police fire by launching bow and arrow attacks. The Times of India of 26 May reports: ‘The death toll in yesterday’s police firing at the Nakshalbari area in Darjeeling district on an armed mob of Santhals has risen to nine. Of these six are women and two children. Santhal women are taking a prominent part in the “peasant movement” in the area.’

Though the rebellion was ruthlessly and rapidly put down by police reinforcements, its sparks flew all over India. Naxalbari became the new metaphor for defiance everywhere. The rebels’ move to redistribute land on their own was a grave challenge to the Indian state. The actual meaning of the rebellion was amply clear to the left leadership now ruling West Bengal as well as Indira Gandhi’s federal government. The news of the mutiny spread like wildfire making international headlines.

Suddenly the eccentric man was in the media limelight. A journalist from an English newspaper was in conversation with him:

Journalist: ‘There are three communist parties now in this country—CPI, CPI(M) and CP(N).’

CM: ‘The first two—I get it. What’s the third one?’

Journalist: ‘Communist Party (Naxalist)?’

(Excerpted with permission from the publisher)