Kalyani Devaki Menon’s book Making Place for Muslims in Contemporary India gives complexity and nuance to the aspirations and concerns facing Muslims in today’s India. A major contribution to religious studies in South Asia, the book is indispensable to students of minority rights as well as area specialists as its lessons are pertinent to conflict in South Asia. Based on the field work in Old Delhi, the book is an account of the shifting everyday realities of Muslims in contemporary India, evoking the people who live there through fascinating accounts of their individual lives.

KD Menon explores how Muslims make place for themselves by disrupting majoritarian constructions of India as a Hindu place that positions upper-caste Hindus as the normative national subject while relegating Muslims to the very fringes of the national imaginary. Author questions the use of difference as an analytic to understand culture and religion and instead focuses on how people make place for themselves amid and across differences.

Menon looks back at the historical status of Old Delhi and it’s bloody transformation from Shahjahanabad to Delhi to Old Delhi and to Delhi-6, and how it continues to survive as a ‘Muslim place’ in a country where Islam has been constructed as ‘foreign’ since the colonial period , where upper-caste Hindus have been configured as the normative national subjects, and where the Hindu Right has dominated the sociopolitical landscape for decades. Author explores how the plural cultural and social worlds of Shahjahanabad had given way to exclusion, prejudice, and distancing. The book also debunks the argument that the marginalisation of Indian Muslims is simply an artefact of the rise of the Right, and shows how this precarity is the result of decades of systemic violence against Muslims in post-colonial India well before the resurgence of the Hindu Right has becoming abundantly clear in recent years.

The book unmasks Indian secularism by revealing the role of state in context of the Partition of 1947. Though everyone suffered from violent conflagrations all over Delhi, but Muslim families suffered disproportionately. The Indian state labeled Muslim families, many of whom were simply trying to escape violence, as ‘evacuees’ and their properties were deemed ‘evacuee property’ and these properties were either seized by the state or illegally occupied by the increasingly desperate Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan. Drawing on the works of Zamindar, Menon argues although both sets of populations had been displaced, the newly-formed Indian state saw itself as responsible only for Hindus and Sikhs.

Relying on Sachar Committee Report released by the Government of India, which demonstrated that Indian Muslims are the most socio-economically underprivileged population in the country, Menon, quoting Judith Butler who describes it as a “politically induced condition” that makes some more vulnerable than others, argues that this marginalisation is enabled and compounded by Islamophobia, stereotypes, prejudices, state surveillance, and detention . The book highlights that the violence has become endemic in India, but what is particularly troubling is the widespread tolerance of it, especially when directed at Muslims or Dalits. While drawing on Ghazala Jamil, Giorgio Agamben, and Butler, Menon shows how multiple discourses are woven together to construct Indian Muslims as an exception, and always suspect, not grievable, and therefore subject to violence. This ‘othering’ underlies the violent denial of belonging and the differentiated citizenship that Muslims experience in everyday life. This differential citizenship is an apparatus through which power of upper caste Hindus is maintained.

While religious practices are central to constructing community and subjectivity, Menon in this book also sees them as spatial practices that can forge cultural commons in places like Old Delhi. The author shows in the book how shared cultural worlds provide an important corrective not only to Hindu-majoritarian understanding of nation but also to academic constructions of religion and religious boundaries in south Asia. Menon insists that rather than focusing on difference, which has dominated how Islam and Muslims have been viewed, related to, and represented for centuries, we should examine how Islamic traditions of all hues have always appropriated ideas from the worlds they inhabited.

Acknowledging the fact that there are arguments, disagreements, and incoherencies among people In terms of class, region, sectarian affiliation, the book highlights the plural identities held by the people who also happen to be Muslim, and how they challenge the tendency to portray Islam “as the most religious religion of them all”, determining every last act, word, and deed of its followers. Analysing the diverse and often conflicting place-making strategies of Muslims from a variety of traditions in Old Delhi, and showing how these intersect with gender and class among other axes of difference, Menon focuses on multiplicity, rather than coherence, and in how living with ‘others’ indelibly marks the narratives and practices of Muslims.

The book also gives an interesting anecdote of challenges an anthropologist faces in conducting a field survey — the pros and cons that come with being female researcher and what it means to be Hindu based in the United States but a beef-eater who is interested in studying Muslims. Author emphasises that while some of these identities may be helpful, these can also limit your accessibility at times. It is perhaps because of these challenges that most of her interlocutors are females.

Menon stresses that though Muslims may experience relative safety in the place like Old Delhi but it comes at a price of reduced visibility and presence of Muslims elsewhere. Even as their acts contest their erasure from the national imaginary, and their narratives and practices articulate alternative visions of community and belonging in which Hindus and Muslims are inextricably intertwined, they can simultaneously enable their containment in places, in the very margins of the national landscape. And yet margins do not always remain so which was clearly manifested by anti-CAA protests of 2019 at Shaheen Bagh, joined by people of all religions, castes, classes, genders, and sexualities illuminated an alternative polity that can still be mobilised despite violent erasures and silencing, and reflected the pluralism that still lingers amid Hindu majoritarianism.

The testimonies of Muslim residents of Old Delhi collected by Menon reveal how Muslims have to contend with structural violence in their everyday lives, enabled by a system that benefits some and both tolerates and normalises the suffering of others. In this way, many young Muslims become increasingly isolated from the mainstream society, forcing some of them towards joining militant groups. This in turn fuels the public opinion that Muslims do not belong in India and are threat to security.

Highlighting the issues of gender against the backdrop of precarious and marginalised position of Muslims in general, stories narrated in the book also show how women used their ingenuity and employed multiple skills, resources, and strategies to help their families negotiate mounting economic insecurity in neoliberal India. In so doing they not only helped themselves and their families, but they also created networks and exchanges through which they supported their communities through difficult times. Their contributions were central not just to production but also to the reproduction of their families and communities, their neighbourhoods and places, making them indispensable to local, national, and global systems and economies.

Most importantly, Menon insists that the lives of these women cannot be understood solely through the lens of religion, or be reduced to their Muslim-ness’. We have to examine how their religious identity intersects with their other identities —as women, labourers, artisans, migrants, friends, neighbours, creditors, debtors, patients, graduates, daughters, and wives— all of which affect their positioning in different ways and shape how they will traverse the social, economic, and political forces operating in contemporary India. Muslim women who are often deemed as exceptional by others in Old Delhi, Menon asserts, are in fact like anyone else in the city or anywhere in the world for that matter: they are complex , contradictory, and plural subjects .

Menon points out that there has been a tremendous upsurge of religious violence in India but the narratives of violence and exclusion are not the only stories that can be told about the country. There are many inclusionary practices of nation and community that still play out in the everyday. In a country where the prevailing narrative expounded by the political establishment, by the media, and by many scholars is about difference, tension, and violence, it is important to pay attention to the narratives like that of Old Delhi Shias, who construct inclusive communities of mourning. These narratives provide an alternative to the exclusionary vision of the Hindu Right, blur boundaries increasingly hardened by rising sectarian violence in South Asia, and belie Islamophobic images of Muslims common in the world today.

Acknowledging that differences and tensions do exist in Old Delhi between Shias and Sunnis and between Muslims and Hindus. Yet to focus only on difference is to ignore the consistent articulations of identities that marginalise difference and blur boundaries between groups . And it marginalises the shared traditions that make place for Muslims in a country besieged by Hindu chauvinists. In a country like India and South Asian region fraught with violent conflicts over identity and exclusionary visions of community, we must pay attention when individuals blur the lines between groups, negotiate tensions, and live with difference in every day life. Through this, Menon presents an optimistic narrative which can illuminate how the shredded fabric of our social worlds might be sewn back together, however slowly, tentatively, and perhaps, inadequately .

Examining the discourse about death, conflicts over appropriate grieving practices, and rituals of mourning among different groups of Muslims, Menon has analysed how mourning enables alternative forms of subjectification. Forging cultural commons and building community across boundaries and over differences, Muslims variously make place for themselves amid exclusionary nationalism of a revanchist Hindu Right. These practices require us to think about Islam as “historical and human phenomenon”, inseparable from politics and entangled in multiple and complex anxieties, interests, and aspirations.

Menon has argued in this book that although securitisation discourses, Islamophobia, prejudice, and violence have ‘secured’ Muslims in places like Old Delhi, and while economic forces capitalise on the politics of religion, class, caste, gender, and place to make some rich at the expense of others, people continue to live, love, and build community in the face of marginalisation, alienation, and dispossession. Today, as institutions of the government are increasingly politicised, as the Constitution is increasingly under attack, and as the world’s largest democracy is increasingly besieged by fascist forces, it is hard to imagine what the future will bring. Menon relies on ethnography to sketch the possibilities which, of course, can unfold in multiple ways. And yet they allow us to sketch those “avenues of hope” that always exist at the interstices of hegemonic forces. The book is perfectly summed up by the verse penned by the late Rahat Indori ,which the author has used as an epigraph for this book viz.

“Sabhi ka khoon shamil hai yahan ki mitti mein

Kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thodi hai.”

(Everyone’s blood is part of the soil of this place Hindustan is not anyone’s personal property.)

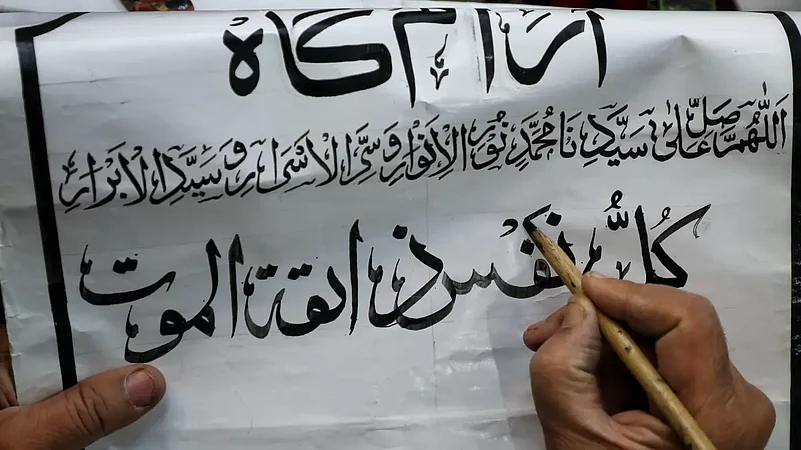

To reach the widest possible audience, the book has been deliberately written in very accessible manner by using common spellings of Hindi and Urdu in the main text. Also, it has as many as 15 photographs along with the descriptions of the photos. These photographs give us a better idea of what people’s lives are like. Though written over a period of more than 10 years , the book is written in a concise manner. It is highly recommended for people who have been to places like Old Delhi and are disheartened at seeing the condition of people living there. It will break your prejudices and biases about Muslims or minorities in India or anywhere in the world.

After reading the book, you will definitely sympathise, if not love, the people living in these places. It is a thoughtful and exhaustive exploration of human cruelty, and perfectly captures how acts such as genocide can happen when one fails to appreciate the humanity of others. It is one of those books that will hook you from the first page and keep you reading till the bittersweet end.

(Manzoor Ahmad Sheikh is a student at the Department of Political Science, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal.)