A Lost People’s Archive

Rimli Sengupta

Aleph

INR 549

The cover of Rimli Sengupta’s book very clearly states that this is a novel. It is in fact her first and is based on information found in her grandmother’s notebook. ‘Novel’ however, is a kind of simplistic description for what is a complex cross-genre work. A Lost People’s Archive spans the worlds of memoir and history, both personal and public – it is above all a Partition memoir that deals with the plight of displacement.

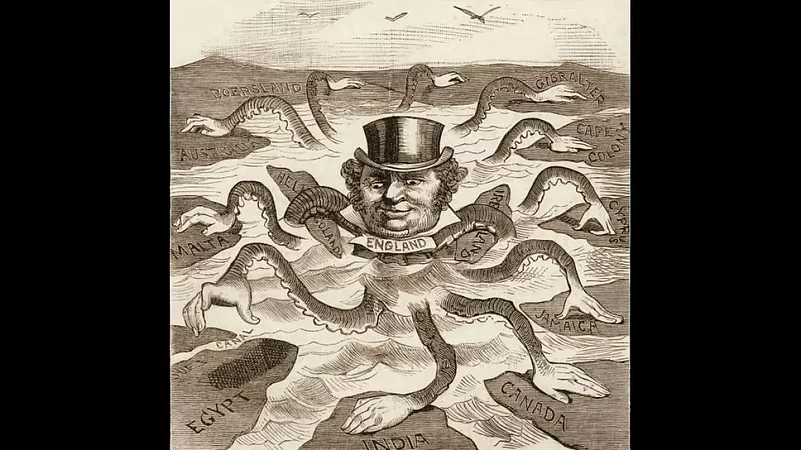

The two main characters, Shishu and Noni are both displaced though displacement affects them in different ways. They grow up together in the small village of Patuakhali in Barishal, in what was then eastern Bengal though still part of India– Shishu the child of privilege, a lawyer’s son, young, keen and easily influenced. Barishal in the 1920s is filled with Swadeshi theories, protests and youth movements against British rule. The beautiful Noni, older than Shishu shares his revolutionary fervour and love for banned books – the two read Saratchandra’s Pather Dabi (Right of Way) together and discover theories of how both men and women can contribute to the cause of freedom. The two, however, are doomed to separation. Noni through marriage and Shishu through the results of activism.

Influenced by the Tarun Sangha and its leaders, Shishu gets drawn into active swadeshi action, following the footsteps of Khudiram Bose who was the youngest revolutionary to be hanged by the British, despite the fact that he assassinated the wrong target. The 14-year-old Shishu is more successful in his attempt and goes to jail but not to the gallows because of his age. He finds himself a kind of hero because of his youth – not that it saves him from hard labour and force-feeding things that were actually meted out to British suffragettes and prisoners like Oscar Wilde too.

Shishu sings, writes poetry and manages to get letters across to his Noni-di in an uneven but strong thread of communication. Sengupta includes some of Shishu’s poems that portray his changing emotions – Noni-di is his muse and he is in some sense her influencer and the saviour of her marriage. Following his example, Noni begins to talk to the women in her area on the subject of independence and empowerment and the fact that she has a heroic swadeshi as her friend arouses respect in her husband who also has swadeshi leanings.

Sengupta describes jail life in Barishal, then Calcutta and in the infamous Cellular Jail in the Adamans to which Shishu is finally transferred which is obviously the result of detailed research and family narratives. She also covers the changing theories among those fighting for freedom – how some were moved by Gandhiji and converted to non-violent forms of resistance while others subscribed to the philosophies of Karl Marx and the Russians and began to discuss communism in jail.

There is an undercurrent of Hindu vs Muslim rivalry which confuses Shishu from the beginning - he cannot understand how the downtrodden Muslim population of Barishal can be swayed by the theories of upper-caste feudal Hindus. As time passes we know that this will become a tsunami released by the Partition. Sengupta’s readers have the advantage of foreknowledge. From the beginning, we know that Shishu will survive and that he will meet his Noni-di again. However, as in all stories where the reader knows what is going to happen the intrigue factor lies in how the author describes the occurrences.

Sengupta describes histories events and conversations between revolutionaries in the minutest detail. She also records events as they would appear in a history book – Shishu’s observations as he begins to work with the village women as part of his Communist missions, the Great Calcutta Killings with their lynchings. The only thing she does not describe in such depth is the Bengal Famine talking instead about Ray’s Ashani Sanket being the weakest of his films born on the arches of Babita’s plucked eyebrows.

Shishu and Noni-di have their different perspectives on what the wave of division meant to them and how they found their way to India. There is also the fallout after the Bangladesh War which saw West Bengal invaded by Bangals (Bengalis originally from Bangladesh) with no homes to call their own and the creation of new neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city. This sets a context for why, post-Partition, many people had no certificates to prove their nationality and throws up the CAA issues of the twenty-first century.

Sengupta even introduces the ghost of Shishu speaking through the charred pages of the notebook narrating his story though the historicity of the narrative does not change. There are subtle touches of poetry in the descriptions of night on paddle steamers or the bells of East Bengal but for the most part, Sengupta avoids descriptions. What the book does best is convey the tangle of identities and how an entire world and way of life went missing due to what everyone at the time thought would lead the way to an ideal world of freedom. The only thing that held in the face of hopelessness was the bond of poetry and hope – and in the case of Rimli’s grandmother a rootedness that came through good fortune.