Hitendra Patel

Adhunik Bharat Ka Aitihasik Yatharth | Rajkamal Prakashan | 430 Pages | Rs 499

“Click! Click! Snapshots from different standpoints.” This is how Hindi novelist and revolutionary, Yashpal, captured the historic Tripuri session (1939) of the Indian National Congress when the internal differences between the party’s dominant factions came out in the open. A very ill Subhas Chandra Bose is being photographed by journalists while attending the session on a stretcher. In this way, the emphasis upon different standpoints for recording and interpreting an important moment in history gets underlined. As historian and academic Hitendra Patel quotes extensively from Yashpal’s Meri Teri Uski Baat (1974) to delineate what is portrayed as a titan clash between Mahatma Gandhi and Bose in the session, readers are offered a much-animated retelling than the usual dry and dense academic prose.

Patel recasts and rescripts historical narratives through what he calls “political novels”. No, this is not a restatement on the established genre of historical novels. He has not simply used historical novels—a novel set during a period of history that tries to relay the spirit, mannerism, and social conditions of a past age with truthful detail and apparent fidelity to historical facts. Patel does something pioneering to make use of some novelists who were political activists, indispensable to the intelligentsia and history of ideas, and had clear ideological inclinations to create a political history based on their novels. This offering is not a ‘history of literature’ or a work of ‘literary criticism’, but a rewriting of political history with ‘political novels’ as primary sources.

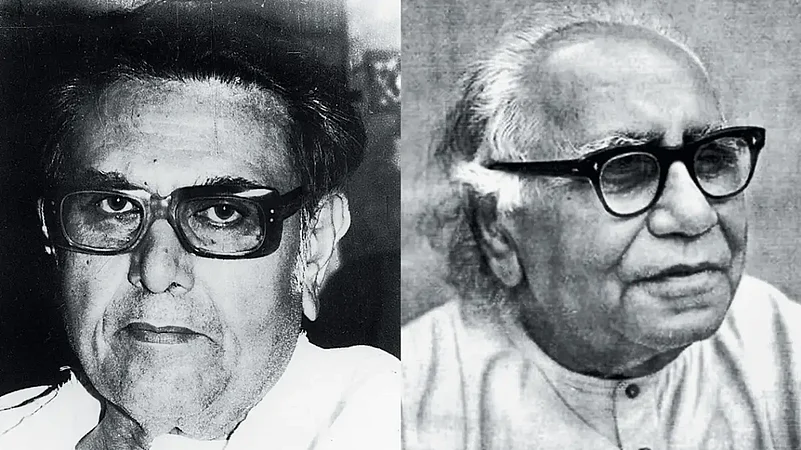

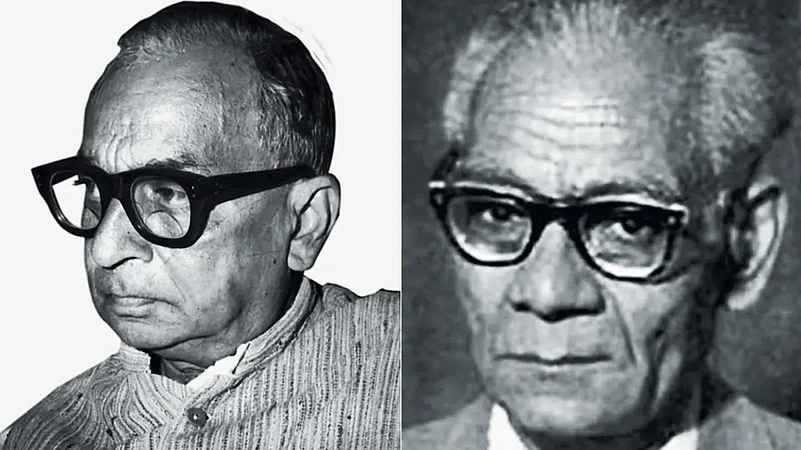

Patel has identified a range of South Asian authors’ viz., Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Qurratulain Hyder, Rahi Masoom Raza, Intizar Hussain, Phanishwar Nath Renu, Bhisham Sahni, Krishna Sobti, Kamleshwar and Amarkant, among others, who help us to decode and rewrite the narratives of South Asian political and cultural histories, including the socio-political truths of the freedom struggle.

Among the various choices, Patel settled with four Hindi novelists, namely, Bhagwati Charan Verma, Yashpal, Amritlal Nagar and Guru Dutt. He shows how these novelists in their accounts have dealt extensively with different strands of politics as they emerged, collided, and conflated into each other. He identifies four such political strands—the Gandhian mass movement, armed revolutionaries, Communists, and Hindu nationalists, and respectively, offers a ‘close-reading’ of his novelists peeling the layers of the ‘political’ in them. How such an exercise can do wonders in the hands of a historian is on display here. Of course, there is no clear categorical classification regarding which novelist stands for what political strand because of the overlaps in the historical narrative. Most of these novels collectively cover the period 1917-64, which Patel attempts to chronologically reinterpret in the light of ‘fresh sources’.

The question that then warrants some attention is what new perspective does the author offer? History writing, globally, has witnessed the Hayden White challenge—where the American historian potently used tools of literary criticism—showing historical texts are marked by strategies of explanation that include arguments, employment, and ideological implications. And hence, the sacredness of “how the historians interpret something” was left sacrilege. Historians such as Sudhir Chandra, Vasudha Dalmia and Krishna Kumar have periodically invoked Bhartendu Harishchandra, Premchand, Maithili Sharan Gupt, among others, to comment on the formation of regional consciousness, nationalism, and ‘Hindu conservatism’. Most of these historians always used literature to understand the past because of the clear consensus in the Indian writing world on separating literature and history. Patel blurs this difference. He makes use of literature somewhat radically. He takes the arduous task of analysing political history through literary representations head-on.

Unlike others who have written about certain representations of the past through literary sources, Patel allows his novels to speak as popular history. Not the formal, academic one. After meticulously criticising historiographical strands in a long ‘Introduction’, he unravels the politics of history writing, which for him, was always political! He has never admitted to the fact in writing, but has dropped enough hints for readers to gather and untangle that present predicaments of the public history could be a result of the same political unfolding around the contestations of pasts.

In this regard, in the book spread thematically across five chapters, the last chapter that provides a reading of Guru Dutt becomes crucial. It views Congress politics through the lens of Hindu nationalists as reflected in Dutt’s novels. The dilemmas, judgements, and analyses of Congress politics by various characters in these novels are still relevant and present a context to the goings-on in the grand old party today.

In the same spirit, the various reasons on the Gandhian mass movement, Khilafat movement, non-cooperation movement, internal politics of Congress, Quit India, World Wars, and a kaleidoscopic quotidian in which the characters by the four aforementioned novelists speak, provide the historian with opportunity and ground to contest his own training.

However, as a historian rooted in the formalism of academia, Patel does not go easy on his sources. He ensures readable and handy biographies of his novelists to provide a rationale for their perspectives and literary lenses. Readers are made aware of the “moral universe” of the novelists, and are provided with an entry gate to the thoughts of the authors before they could be introduced to their “politics”. After all, these four Hindi novelists as key representatives of the intelligentsia, made calculated risks and ascertained their ideological implications clearly. For instance, Bhagwati Charan Verma’s Bhoole Bisre Chitra (1961), with characters as diverse as Gyan Prakash, Ganga Prasad, and Rajbihari, provide different readings of the political moods in the freedom struggle of the 1920s. Similarly, a key event such as Tripuri Congress has Verma and Yashpal offering disparate historical perspectives.

In the book, Patel has addressed the elephant in the room. By choosing four novelists and relying on them as historical sources, he outlines the different imaginations of the nation in the freedom struggle in his lucidly-written prose. It is true that while the Gandhian mass movement garnered widespread acceptance, it never succeeded in obliterating other contenders, especially the Hindu nationalists who have made a comeback in contemporary India. Therefore, while the book makes a case for decoding popular historical perceptions about the past, it may not always be validated by academic consensus on an issue.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Back From The Past")

Shaan Kashyap is a researcher of modern Indian history at JNU, New Delhi