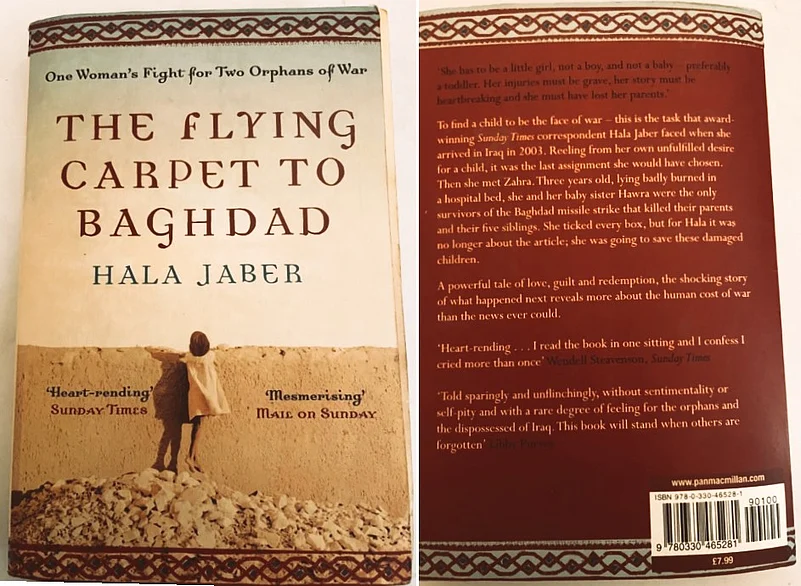

The Flying Carpet To Baghdad By Hala Jaber

Published by Pan Macmillan, 2009

“Is it okay to benefit like this from other people’s misery?”

— Hala Jaber (From her speech upon winning an award for her reports on the Iraq War)

The book written by Hala Jaber, a (British) Lebanese journalist offers a personal account of her experiences in Iraq as a foreign correspondent for Sunday Times during the US invasion in 2003.

The book, which has 18 chapters, covers the themes of devastation caused by war on innocent civilians beyond numbers that the news could ever tell, as well as the courage of journalists and photographers who place themselves repeatedly in danger to cover war.

It explores Hala's personal struggles with infertility, her decision to immerse herself in reporting on the Iraq war, and the re-awakening of her maternal instincts by two orphans of war, Zahra and Hawra. The last thing she expected was to find herself trying to save these little girls.

The book begins with Hala searching for a child to be the face of war. She was looking for a wounded girl, between one and five years old, whose parents had died and whose “pretty face was more or less unscathed" for the slot on the inside pages of the newspaper, as instructed by her Editor. The paper was planning a fundraising campaign for the children worst affected by the war. The face and story had to move readers; otherwise they would not donate money.

As a journalist, Hala understood that the most heartbreaking orphan's story would raise the largest amount of money. But as a woman longing for her own baby, she knew that the sight of distraught children with no mothers to wipe their tears would test her to the limits of emotional endurance.

Hala, married to an Englishman named Steve, whom she met when he arrived in Beirut to cover the Lebanese civil war as a photographer, tried everything she could to get pregnant. But nothing helped. Throughout the book, Hala is very open about her insecurities regarding not having a child.

Eventually, she came to terms with her inability to conceive. “Okay, so I was not meant to be a mother but by God I was a good reporter. What was to stop me becoming one of the best?” Hala says.

Jaber travelled to Baghdad with Steve to cover the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. The effort to get pregnant and the void it had caused in her was being replaced with a sense of purpose and promise of another kind of fulfilment.

While looking for a war orphan, Hala came across 3-year-old little girl Zahra, severely burned in a US missile strike that killed her parents and five siblings. Zahra and her infant sister Hawra were the only survivors.

As the little girl was calling for her mother- “cover me up, mama”-who would never come, Hala longed for a daughter like her who would never appear either.

“I had been unprepared for how strongly I would respond as a childless woman to this motherless child,” Hala writes.

Amid her struggle “to select and reject injured children,” for the newspaper’s campaign, she had to remind herself, whatever her personal feelings, she had a job to do. She tried her hardest to remain aloof like a good journalist, but the discovery of Zahra made her see the suffering more than a strong news story.

Looking at Zahra, her old dream, which she had to abandon when she was unable to conceive, returned. She and her husband Steve consider adopting Zahra and Hawra, and giving them a ‘good life’.

The book provides firsthand accounts of the human cost of war in Iraq. Hala narrates the harrowing encounters with injured and describes scenes of dead bodies piled upon one another at the hospitals in Baghdad. Amid the looming deadlines for her stories, Hala wanted to save the victims of war. She wanted to save the children.

“The shooting and bombing were destroying so many families like Zahra’s who were not interested in fighting the Americans, but were simply trying to survive,” Hala writes. At times, she found herself questioning God’s wisdom even though she knew it was blasphemous to do so.

Hala, being a Lebanese and Muslim, understood the Arab point of view, and as the wife of an Englishman and an employee of a London newspaper, she understood the western way of thinking. She was in the privileged position of being able to straddle two worlds and explain one to the other.

This book should definitely be added to your reading list, especially now that West Asia has once again become a hotspot of volatility.

The book offers an insight into the terrible human cost of war along with the inner world of a journalist struggling with personal sensitivities and professional demands. Hala's story is also for the women struggling with infertility and societal shame.