Much of the discourse on domestic and international politics, terrorism, extremism etc. has become stale and eminently predictable. If it is about the Middle East, riven with all sorts of internecine conflicts, the discourse is even staler. ‘Banality of evil’, and even virtue, so to speak. When you feel desperate about the futility of it all, poetry and fiction offer you an alternative universe, which provide you with the much-needed escape, without making you insensitive to the present.

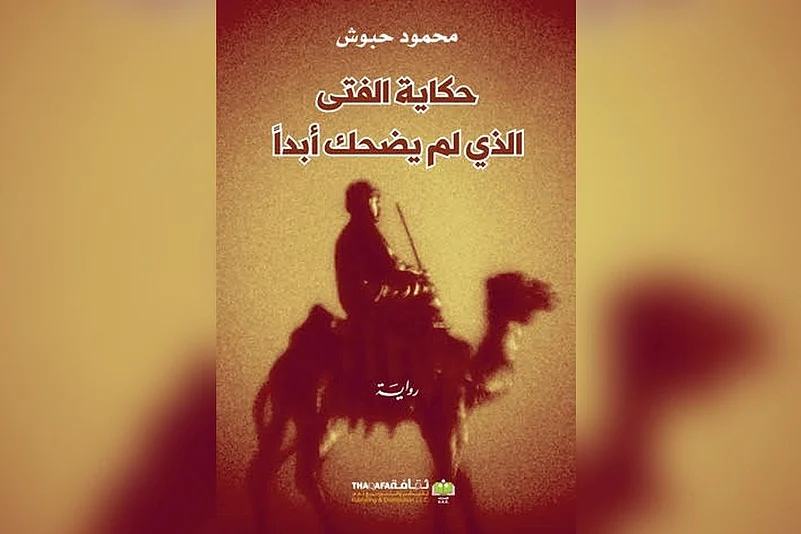

‘Hikayat al Fata alladhi lam yadhhak abadan’ (‘The Tale of the Boy Who Never Laughed’) by the young Palestinian writer/journalist Mahmoud Habboush is one such book that takes you back a few centuries, but still manages to speak eloquently to the present. It is an unusual book for a variety of reasons. Chief among them is that it is written in medieval, and not in modern contemporary, Arabic. Although never explicitly stated in the book, it is a story that seems to tell the Arabs, and the Muslims: enough of sentimentality and visceral excesses. Now start using your brains!

The protagonist in the novel, unnamed as all other characters and simply called the boy, was born a precocious child with a humongous head and a permanent frown on his face. He did not cry at birth like other newborns. In fact, he never cried, smiled or laughed in his whole life. The looks and ways of the boy were bizarre to an extent that the Imam of the local mosque feared that he might be Al-Masih ad-Dajjal (fake messiah), the equivalent of antichrist in Muslim belief. He became a butt of ridicule in his village because of his frown and his weird demeanour.

He was so obsessed with books from early on that no normal human activity interested him. He experienced no emotion and the only faculty in him that seemed to function was his superior intellect. Even his kindness was intellectually induced. So was his belief in God and faith, almost in a Spinozan sense. Anguish, grief, happiness, excitement, agony, love, romance, envy, anger, lust, self-indulgence – he remained impervious to them all, though he could intellectually hold forth on all of them. At the behest of the king of Aleppo, he even authored a brilliant treatise on laughter, which won all-round admiration.

The underlying theme of the novel is the desirable centrality of the intellect in human life – not only as a source of ideas but also emotions. If your feelings emanate from your brain instead of the heart, they will never transcend the realm of reason. The protagonist at one point in his life becomes an intellectual giant in the court of the king of Aleppo, who was a learned patron of scholars and thinkers. The book narrates with finesse some of the extraordinary medieval debates that electrified the royal court with their insights and differing perspectives on issues of theology and philosophy – divine will, predetermination, eschatological conundrums, human destiny, Quranic precepts, human conditions and mysticism.

The primacy of the intellect as a trait or a virtue is not an altogether new theme in Arabic literature, but it is perhaps the first book that entirely focuses on it. The book reminded me of a fascinating conversation between an English woman and a pre-adolescent Mustafa Saeed, the protagonist in Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih’s modern Arabic classic, ‘Season of Migration to the North’. “Mr. Saeed, you are a man totally devoid of mirth. Can you not forget your intellect even for a moment?” asks the woman.

Unlike Mustafa Saeed, ‘the boy’ in Mahmoud’s novel inhabits no world other than that of ideas - religious and secular. A reluctant, highly intellectualized love affair that buds between him and a Roman slave girl gifted to him by the king and set free by him soon after brings about a small transformation in him, moving him slightly away from extreme intellectualism. Marriage with the girl alters some of his congenital eccentricities and pushes him subtly but surely into behaviorally imbibing the central theme of his scholarly efforts – Al Wasatiyya or moderation. Interestingly, the long intellectual conversations between him and the girl reflect a remarkable spirit of gender equality uncharacteristic of medieval times. (Except for the sex post-marriage, the interaction between the two is always about ideas, with the exception of a couple of playful remarks by the girl).

‘The Tale of the Boy Who Never Laughed’ is a parable that tells the reader that it is important for Arabs and Muslims to learn to approach life and world more intellectually than sentimentally. At the same time, it also alludes to the limitations of pure intellectualism, which robs its practitioners of the simple pleasures of life. When lust overtook him for the first time in all its novel intensity on the night of his wedding, ‘the boy’ realizes to his rude shock and shame that his claim of having complete control over his emotions was not actually based on any real experience, but mere theoretical posturing.

(The author is a cultural critic and commentator writing in both English and Malayalam.)