As the story goes, told and retold in colourful pages of the Chandamama and Amar Chitra Katha comic books over decades, it has always been about good versus evil. Generations have grown up on stories of Indian mythological figures, gods and demon kings, battling each other for cosmic balance. Those were also the grandmother’s tales, simple and straight, black and white—about righteous heroes vanquishing evil incarnates. They were the kind of story loved by children and adult alike. They still are. But along the way, came a twist in the tale.

Enter the millennials, used to flipping pages of manga on the i-Pad and not so much considered the bookworm. A whole new generation born and brought up in the digital era has been stereotyped as an inveterate gizmo-loving lot of geeks, unabashedly averse to carrying a book alongside an i-Pad in their backpacks. Not any longer. The seemingly uber-cool generation appears to be in for an image makeover with techno-savvy dudes stumbling on an unusual genre of storytelling: mythological-fiction.

Even as the foundation stone for a grand temple is laid by Prime minister Narendra Modi at Lord Ram’s birthplace in Ayodhya on August 5, the ‘fictional’ Ram is back in a new ubiquitous avatar as the god of paperbacks. And so are Shiva and a phalanx of other deities from the tomes on mythology. With dozens of young novelists revisiting the hoary epics to piece together gripping thrillers around mythical heroes in contemporary settings, Indian fiction writing had never been closer to ‘divinity’ in the past.

Stagecoach

The Gen Z is simply loving it. It appears to have fallen back upon something readable that has actually lured it back from under the spell of DC comics after a long while. The protagonists of these books are a far cry from the western graphic novels featuring supermen on a mission to save the planet from an imminent disaster.

Far from it, they are modelled on all-too-familiar heroes or anti-heroes from popular Sanskrit epics and other homespun mythological yarns of yore. A fresh perspective on such characters by a bunch of innovative writers in Hindi and other indigenous languages has spawned a Gita Press-meets-J.K. Rowling kind of crossover books, where the central character is not inspired merely by perennial favourites like Ram, Krishna or Shiva but also a slew of other not-so-divine mythical figures, who have held the readers of successive generations in thrall with distinctive traits of their own.

Interestingly, it is the world of Hindi fiction where the proliferation of such characters is most discernible at the moment. Of course, there has been no dearth of books on mythological characters in the mainstream or popular literature in Hindi, or for that matter, in the domain of other Indian languages over the years. Gita Press, Gorakhpur took mythology to almost every household in the north with its low-priced books. In the modern era, renowned Hindi litterateurs such as Maithili Sharan Gupt, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Hazari Prasad Dwivedi and Agyeya have all interpreted mythological characters in their own way. With highly acclaimed works such as Urvashi, Urmila and Yashodhara, the list is too exhaustive to be enumerated here. Similarly, Marathi, Bangla, Odia, Assamese, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam literature have all been replete with similar books. Eminently readable titles in Marathi such as Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar’s Yayati, Shivaji Sawant’s Mrityunjaya are available in Hindi.

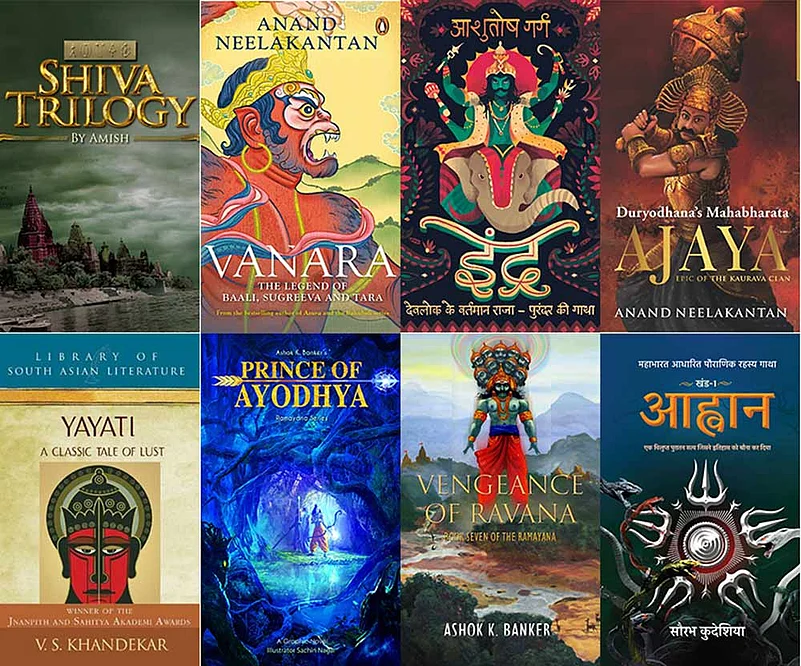

But the latest trend of authors spinning a new yarn around mythical characters actually began in English about a decade ago with the ascendancy of the likes of Devdutt Pattanaik, Amish Tripathi, Ashok Banker, Ashwin Sanghi and Anand Neelakanthan whose best-sellers continue to fly off the shelves. The popularity of Ameesh’s Shiva trilogy, Patnaik’s The Pregnant King and Banker’s Ramayana series has since led many publishers to explore the potential of this genre in Hindi and regional languages.

Today, vernacular novelists are diligently exploring indigenous characters from mythology, right from Ashwathama and Indra to Shakuni and Shoorpanakha, all fascinating figures in their own right but rarely written about in the past. Of late, books like Shani: Pyar Par Tedhi Nazar by Pankaj Kaurav, Ravan: Ek Aparajit Yoddha by Shailendra Tiwari, Ashwatthama and Indra by Ashutosh Garg, Shakuni by Ashutosh Nadkar, Rankshetra by Utkarsh Srivastava and Neelkanth: Parajay Ka Vish by Sanjay Tripathi, have found enough takers across the Hindi belt.

Explaining the reasons behind its popularity, Amish says that the people in India never get tired of or bored with the stories of their deities. “They can listen to such stories, told and retold from diverse perspectives, many times over,” Amish tells Outlook. “That is why so many books on different mythological characters are coming up lately.”

The best-selling author finds it heartening that a lot of books are now being written in Hindi because it “enriches and lends strength to our culture and traditions”. (See column).

Devdutt Pattanaik, another best-selling author on mythology, believes that the trend actually started off with the popularity of Harry Potter in the new millennium. “When Harry Potter became popular and films were made on his character, people’s interest in folk tales and mythological stories increased manifold,” he says. “It is now happening not only in India but across the world. I believe mythological characters have become part of the literature everywhere.” According to Pattanaik, every individual is endowed with the power of imagination and a natural flair for telling stories. “These stories have thrown open all gates of imagination for the writers. Maybe that is the reason why such stories are being lapped up by the readers.”

Interestingly, all-time favourite epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata continue to fascinate the new authors the most. Hastinapur and Ayodhya, the two ancient cities at the heart of these epics, remain the veritable goldmines for them. Ashutosh Nadkar, for one, has based his book on Shakuni. In fact, characters like Madhavi, Draupadi, Satyavati, Kunti, Gandhari, Bhishma, not only generate enough interest in the average reader but also offer immense scope to the writers to tweak their content in modern context. Hardly surprising then, publishers are backing such stories to the hilt these days.

Minakshi Thakur, publisher, Eka (Westland), says that Ramayana and Mahabharata have existed for centuries, and writers have retold their stories not only in English but across Indian languages. “They are not called epics for nothing. There are a hundred stories within the larger story which can be told from so many angles and from so many points of view,” she says. “If Sita in Amish’s novel is a warrior princess, in Bhyrappa’s Uttara Kaanda, she has been described as an expert farmer.”

Critics, however, ascribe the success of such stories to the meticulous selection and presentation of controversial, neglected and paradoxical characters or episodes from the mythology. But does a writer have the liberty to rejig any age-old narrative to suit his purpose of making it appealing to a new generation of readers?

Anushakti, writer of an eponymous novel based on a neglected mythical character called Sharmishtha, does not think it to be improper. “Female characters have limited space in mythology and if you leave aside a few powerful characters, a woman’s perspective is hardly manifested in such stories,” she tells Outlook. “That is why I wrote Sharmishtha the way it should be told, or for that matter, the way it should have happened in the first place. It is a story about the rights and respect which a woman deserves without any gender discrimination.”

The writers, however, have to be meticulous enough in writing such stories because, as Aditi Maheshwari of Vani Prakashan emphasises, it is a huge responsibility to publish books on mythological characters. “Mythological characters need to be redefined because the definition of human values keeps changing with time,” she points out.

Nonetheless, it is quite interesting to see mythological fiction whipping up curiosity of young readers in the era of smartphones, just the way the books of ‘pop’ authors like Chetan Bhagat climbed the popularity charts in the early years of the new millennium. A class XII student in Delhi, Akshat Sharma, says, “The book on Ravan is my favourite because it has made me aware of many unknown facets of his personality. In fact, I like the stories behind the dark characters from mythology.”

And there are so many of them, characters with innumerable shades of grey. With the millennials showing palpable interests in mythological fiction, most publishers are now vying with each other to meet the growing demand. Vaishali Mathur, publisher, Penguin, believes that it is part of a larger trend. “The youth are linking it up to the understanding of their roots and the modern interpretation of the situations and the characters,” she says. “Their desire to read more mythology is accompanied with the reading of more history and politics as well.”

Nonetheless, such a trend would not have been possible had there been no surge in their sales figures. Kapish Mehra, CEO, Rupa Publications, says that these books elicit a good response from the sales point of view. “We have published several books based on mythological characters,” he says. “They are generating good responses across the mediums. Look at television where several serials on such themes are running.”

True. There was a time in the pre-millennial era when comics and magazines such as Amar Chitra Katha and Chandamama catered to young readers. However, their popularity diminished with the advent of colour television, which ruled the roost with serials like Ramayana and Mahabharata in the mid-1980s. When the same serials based on the two of greatest Indian epics were re-telecast at the start of the lockdown on Doordarshan earlier this year—more than three decades after they were made—they smashed all records in terms of viewership: a giveaway to the fact that the interest in mythological characters was only waiting to be rekindled beyond the world of the Hindi fiction.

Shailendra Tiwari, author of a popular book on Ravan, says that the scope of writing anything on the epics is quite vast. “These epics have many nuances which help a writer come up with something new and innovative,” he points out. “People still like to read and hear all kinds of stories, from the magnificence of the Kauravas to the simplicity of Ram.”

It is the burgeoning interest of the youngsters that has prompted Venus Kesarwani of Redgrab Books, the publisher of Sita Ke Jaane Ke Baad Ram (2014), to print maximum titles on mythological characters. “Our books are read mostly by the youngsters and we reach out to them through book fairs and social media,” he says. “Our Rudragaatha still sells the most amongst the youths.” Kesarwani admits that though his publishing house had faced difficulties when it set out to print such books a few years ago, “the sales have picked up in a big way now”.

Publisher of Neelkanth, Kapil Singh of Manjul Prakashan, too says he receives very good response to such books. “After Ram, Shiva is the most popular mythological figure among the readers,” says Kapil who has also brought out the e-format of his book on Indra primarily to cater to the new generation.

Still, regardless of the rising popularity of Hindi or regional books on mythological or quasi-mythological characters, they appear to be miles behind English titles in terms of sales figures. Publishing industry watchers cite the absence of effective marketing strategy as the main reason behind it. But many writers and publishers remain optimistic that the day is not far when Hindi too will have a Devdutt Pattanik, an Ashwin Sanghi or an Amish of its own.

Ashutosh Nadkar, writer of Shakuni, looks at the yawning gap in a different way. He says most people from the Hindi heartland keep hearing stories of Ram and Sita or the Sundarkand chapter from Ramayana since their childhood. “Many of them actually learn them by rote, and do not feel the need to buy books on mythology” he says. “That is why fewer copies of such books are picked up by the Hindi readers. Having said that, it is a good sign that the new generation is revisiting them now,” he states.

The soaring popularity graph of mythological fiction, however, is not confined to English or Hindi alone. A similar trend is discernible in the regional languages as well, though there are fewer original ones available for local readers. Nearly a decade after he came out with the Kannada translation of Amish’s Immortals of Meluha, Mysore-based author S. Umesh says that readers still get in touch with him, asking for more books in the same vein. “If you give a different perspective to mythological stories, people will accept, particularly the young crowd. That is 100 per cent sure. There is always a market with youngsters,” says Umesh who translated Ameesh’s 2011 book.

Concurs Sameer Joshi of the Dharwad-based Manohar Grantha Mala, which brought out the Kannada translation of Devdutt Pattanaik’s Sita this June, following up from Jaya a few years ago—both to good response. “We are planning to translate more of Pattanaik’s books now,” he says.

In recent years, there have been other examples—writer Anand Neelakantan’s Asura and Rise of Sivagami have been translated into Kannada. “All age groups are reading now,” says Prakash Kambathahalli of Ankita Pustaka, who has a finger on the reading pulse. But there’s also a conundrum, says Kambathahalli. There haven’t been many original Kannada works in this genre. “It’s not that there’s no market. Perhaps many aren’t aware that there’s a market,” he reckons.

Of course, mythology has been an essential part of Kannada literature all along and has always connected with the reading public, points out journalist and writer Padmaraj Dandavati, who recently translated Pattanaik’s Sita into Kannada. Take, for instance, S.L. Bhyrappa’s classic re-telling of the Mahabharat, Parva (1979) which has run into innumerable reprints. Or Irawati Karve’s Yuganta which was translated into Kannada from the original Marathi. Before that, there were Vachana Bharatha by the scholar A.R. Krishna Shastri and Kuvempu’s Ramayana Darshanam. The epics might still find readers across age groups but awareness among the youth about modern Kannada literary work—for instance, Shivaram Karanth, U.R. Ananthamurthy, Lankesh or Masti Venkatesha Iyengar—is waning, rues Dandavati.

That’s also an oft-heard lament—a general observation is that the average age of the Kannada book-loving crowd is 40 and over, suggesting that younger readers have drifted away. Besides, print runs in Kannada cannot be compared to English because the reader base is lower, says writer Umesh. Partly because readership is confined to the state and secondly, the price point. “People may be interested but when the price goes high, they hesitate to buy,” he says. Typically, books priced below Rs 200 move faster. Of course, it all depends on the titles too; his first translation was the best-selling The Last Lecture by Randy Pausch, which has sold 45,000 copies so far.

In neighbouring Tamil Nadu, since Tamil translations of Amish Tripathi and Devdutt Pattanaik are now freely available they have notched up quite a few numbers there. Though the original English version continues to be bestsellers, their translations have found a ready audience among Tamil readers,” says Ashwin, proprietor of Odyssey, Chennai’s largest bookstore.

Srinivasan, owner of Alliance Publications, one of the big publishing houses in Tamil Nadu says that the Mahabarata and Ramayana by Rajaji and Cho Ramaswamy continue to be the biggest bestsellers in the Indian mythology section. “During our annual book fair in December-January, their books sell like hot cakes even today. True, we do not have modern mythology writers like in English. After the demise of Tamil literary giants like Ki. Va. Jaganathan and P. Sri, who dominated the Tamil mythological scene during the ’60s, we do not have authors with similar following,” he says.

In Odia, books based on mythology have been there as long as one can remember. Three of the best known examples—Jagyanseni by Jnanpith award winning author Pratibha Ray, Sriradha by poet Ramakant Rath, and Bansha by poet Haraprasad Das, both of whom won the prestigious Moorthi Devi award—were all written in the ’70s and ’80s.

Some of the other well-known books based on mythological themes are Gopapura by acclaimed writer Ramachandra Behera for which he won the Sahitya Akademi award in 2005; Charu Chibara Charjya by Pradip Dash, which won the Sarala Award, the most prestigious literary award outside the government sector, and Rani Shyamabati by Archana Nayak.

In many ways, celebrated writer Laxmipriya Acharya, who won the Odisha Sahitya Akademi for her book Amba in 2016, is a pioneer of sorts in the genre. She has been writing since the 1980s and has authored a host of books based on mythological themes dealt with a contemporary context. She does not agree that it is a recent trend. “Ramayana and Mahabharata have been in existence for 5,000 years and have continued to inspire writers and poets. And I have no doubt whatsoever that books on mythology would continue to get written in future too,” she tells Outlook. She, however, is yet to read any of the books written in English by Pattanaik and Amish.

Eminent writer and critic Asit Mohanty experimented with writing on the contemporary Odia literary scenario based on characters from the Mahabharata. The highly acclaimed articles were serialised in a fortnightly column in Odia newspaper Suryaprabha over a period of two years.

Indian millennials will continue to be marvelled by the powers of a Thanos or a Thor. But they will also continue to find new heroes to celebrate in their own cosmos of mythology. Though many believe that this newfound love for mythological fiction could be just a fad, the optimists believe that the epics will continue to be told in a million new ways. “They are so many stories rolled into one epic: a war novel, an epic verse, the story of gods, incarnations who can be humanised. There are great love stories in them, there is politics, the tussle between good and evil, intrigues in court, magic, espionage, adultry, polygamy, monsters, you name it,” says Minakshi Thakur.

Finally, RAM is much more than just random access memory for those hooked to their smartphones and laptops.

(With inputs from G.C. Shekhar, Ajay Sukumaran and Sandeep Sahu)