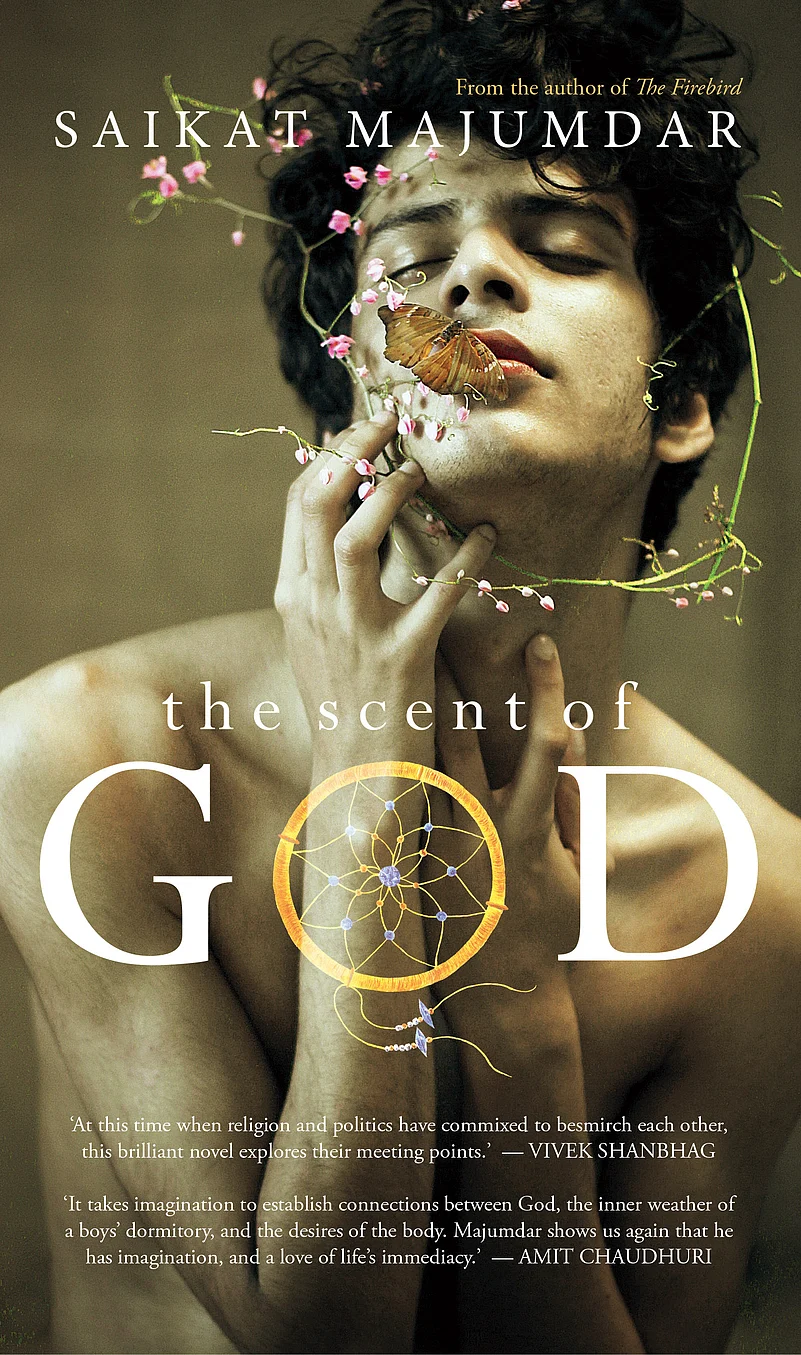

Saikat Majumdar’s book The Scent of God is set in an all-boys’ boarding school run by a Hindu monastic order in late-twentieth century India.

The book talks about Anirvan, a young student, who dreams of becoming a monk. But as he seeks his dream, he finds himself drawn to a fellow student, and they come together to form an intimate and unspeakable relationship.

What is the meaning of monastic celibacy? What holds the brotherhood together?

Against himself, Anirvan gets sucked into a whirl of events outside the walls of the monastery. When the love of his life returns to him, the boys’ desire for each other push them towards a wild course of action. But will that give the boys a life together in a world that does not recognize their kind of love?

Below is an excerpt from the book:

The Magic Wrist

Whenever India played Pakistan, the villagers in Mosulgaon wanted India dead. For the boys, that was the best reason to watch cricket on TV. The village was just outside the walls of the hostel; their roars and firecrackers were real, an enemy of their own!

That Saturday, India was to play Pakistan. But even such excitement paled next to that of watching it in the common room of Bliss Hall. It was a dark festival. All eighty of them packed on the floor of the room, on the thick, ribbed carpet. The door was closed and weak sunlight filtered through the glass pane of the windows. Garish light flickered from the TV set perched on the table in front.

The boys wanted to shout and scream but for Kamal Swami sitting on a chair at the back. Kamal Swami was unbeatable on the cricket field, he aimed like Arjun. His saffron robes flapped wildly in the wind when he bowled, and before you blinked, the ball blew up the wicket like a child’s toy-house. But he rarely spoke during matchscreenings, only once in a while to make a rare forecast whether a batsman would stay or get out. And he was always right, so that scared the boys a little.

In the darkness, the common room became a maddening place. No one could see anything. It was like a movie theatre. The blue flannels on the screen and the frenzy of cheering spectators on the stands, all that was visible in the common room of boys who cheered in whispers. The crowd drove them crazy, for the match was happening in Peshawar and the Pakistanis wanted to drown the Indian batsmen in their fierce war-cry. From time to time the boys wanted to smash the TV screen, claw at the brute Pakistanis who waved massive greencrescent flags like weapons at the heroic Indian batsmen who fought their killer bowlers.

‘Cut their dicks off,’ Bora whispered softly at the TV.

‘Dicks slit already,’ Asim Chatterjee roared.

‘Bloody mullahs!’ ‘Firecrackers going off at Mosulgaon,’ someone whispered. ‘They cheer when Pakistani bowlers get a wicket.’

They lived and breathed with this village. One could see the thatched huts from the rooms of the C Block, and if they stared hard they could also spot muddy-looking women bathing. The villagers hated the ashram and they wanted Pakistan to rub the noses of the Indian team in the dirt.

‘Slit-dicks!’ Asim Chatterjee roared again.

‘Asim!’ His name flew and hit Chatterjee like a thunderbolt from the back. Kamal Swami’s voice always pierced like an arrow. Chatterjee crumpled up like a withered flower. He looked big and burly and already had hairy temples and upper lips but it was easy to crack him as under the loud body of a bully there was always shame, the shame of hairy whiskers and upper lips in Class 7 and the reminder that he was a man among children.

But Kamal Swami never had to say much.

Silence thickened in the common room, the TV buzzing alone. The flag-waving Pakistani crowd was gone, vanished into the television and far away in Peshawar. Anirvan glanced to his left. Kajol sat staring at the TV. His face said nothing. The Swami’s voice had not touched him. He never rested till the last equation on his homework was solved to perfection and nobody ever found a balled-up sock under his bed. Was he really watching the match? Or just looking at the TV because they were all supposed to?

The silence became more pointed. Watching Qadir was a bizarre kind of a delight. He began his twisted dance to the wicket and the whole room leaned forward. Anirvan’s weight rested on palms splayed on the carpet on either side, ready to attack. The ball fell at the perfect length before the leg stump, and the batsman tried to drive it towards long-on. The ball caught the edge of the bat andshot at the off-stump like a snake’s tongue. The hawk at the slip caught the ball and the Pakistani team howled like a pack of wolves. A gasp went up in the dark room and Anirvan clenched his fingers to feel Kajol’s palm in his own. It was a soft and small palm, almost like a baby’s. The anxiety of the moment was a disease and one had to share it.

A curly-haired sixteen-year-old boy had appeared to face the guile of Abdul Qadir. His name was Sachin Tendulkar and he had raked up some massive innings in domestic tournaments. But he was just a boy and the devious Qadir would slaughter him soon. They waited.

Anirvan had not let go of Kajol’s hand. It was beginning to feel strange as the moment couldn’t last forever, the moment when one slapped his neighbour’s thigh or clenched a hand in excitement, but he held Kajol’s palm and sensed the moisture in it, the moisture coating his bony knuckles.

He was a boy really, this Sachin Tendulkar, a curlyhaired boy who could perhaps play in the older boys’ school team. It was absurd and delightful to see him in the massive cricket gear—the pad and the helmet and the heavy bat, among these real and famous cricketers. The boys were just happy that Waqar Younis—the deadly paceman—was not there to draw blood with his bouncers. He would come back soon but the trickster Qadir would happily send the boy back to the safety of the pavilions long before that.

Anirvan unfurled each of Kajol’s fingers slowly inside his palm, like he was playing a secret game of numberswith his digits. Kajol had smooth, well-trimmed nails. Anirvan ran his fingers over them and imagined his tiny nail-cutter tucked away carefully inside his desk where everything was arranged like a library catalogue. He was the kind of boy who never trimmed his nails on a day he was not supposed to, like a Thursday, or the day of the week he was born, just as his mother had told him. One who set aside two days in the week when he clipped them after his bath, when they were soft.

Anirvan’s heart beat wildly. Sachin Tendulkar took guard to face Abdul Qadir. Anirvan caressed Kajol’s fingers, feeling the spot behind his knuckles where the skin wrinkled, the spot below it where tiny hairs had sprouted, so tiny and so little, he was almost hairless.

Qadir did his fatal dance. The ball pitched and spun madly. The boys wanted to close their eyes and not see the terrifying sight of the bails flying off the stumps.

Swiftly, the curly-haired boy changed into a battlestallion and hooked it wildly over mid-wicket. A sixer!

The boys gasped and almost forgot to cheer. And then they cheered, a wisp of sorrow in their voices. What a spunky boy! He will kick before they kill him. Soon.

Anirvan squeezed Kajol’s hand. His fingers slid back, caressed his wrist, the baby bone awake on the corner, the veins of his pulse that made up the soft belly of the wrist. It was his to play with. It did not question Anirvan’s claim on it, doing whatever he wanted to do with it. He did not dare to look at Kajol but knew he was staring at the TV. Did he resent having to watch cricket? Perhaps the rowdiness of the Pakistani spectators and the rowdiness of Asim Chatterjee made him wince.

The camera focused on Abdul Qadir, returning to his dancing run-up. A smile danced on his lips. A cheerful snake. He would now kill the boy, split his stumps wide open. Bora closed his eyes and said something under his breath. It was some kind of a prayer. It was odd to see Bora pray, as if he were ill and had no idea what he was doing.

The ball pitched right on the middle stump and spun in the wrong direction. A googly that would sting the leg stump. Smoothly, the curly haired boy pulled the ball over long leg. Out of the field and out of the world!

Who was this Sachin Tendulkar? Who was this boy, really? What kind of guile had made his wrists?

Anirvan’s heart leaped. Kajol squeezed his fingers, quickly, clumsily. Anirvan glanced at him through the corner of his eye; he looked straight at the TV. Where did he have his heart? In Peshawar or with the algebra left unsolved in his room? Somewhere else?

And then Sachin Tendulkar sent Qadir outside the stadium for a third time. His wrist turned like the arc of a revolving planet. The spectators were quiet, in sudden mourning. The boys’ chests hurt with pride and were about to explode. The firecrackers had died out there in Mosulgaon.

Qadir was smiling. The bastard was game!

Everything felt right. Anirvan wanted to bring Kajol’s delicate wrist to his mouth, suck his soft baby fingers one by one. There was an ache in his loins. Everything was taut.

‘Take that you split-dicks!’ Asim Chatterjee howled.

‘Turn off the TV!’ Kamal Swami’s voice struck out like a slap across the room.

Anirvan pulled out his hand sharply from Kajol’s.

Before they knew it, Sunondo Dey stood up in the front row and turned off the television. He loved to follow the vilest orders of the Swami. He hated to see his classmates happy.

The boy with the magic wrist was gone.