That afternoon Ananta brought the rumour that the Commissioner Sahib of the Division had handed over the charge of sarkari administration to Jarnel Dyer Sahib, who was the big jarnel of the troops, to take steps to reestablish the Angrezi Raj again. And, of course, little knots of men and women gathered in the gulley to discuss this.

Nawab Jan said that the Judgment Day, promised in the Koran, was fast approaching. Lachi maintained that the earth may crack up through an earthquake, such as happened in Sindh ages ago. The rest of the women looked to mother for guidance, now that the army was in control. And all she could say was that the Whites ate beef and were red-faced and went to the prostitutes of every cantonment and were mostly men of bad character. They would suit some, she said, obviously referring to Devaki; as for herself, she kept the doors of her house locked from behind against any intrusion by the Tommies.

The next day all these prophecies were fulfilled, when there came sounds of weeping and shrieking and mourning in the Kucha Fakir Khana, and everyone rushed to the house of uncle Dev Dutt and learnt the horrible news of the massacre of Jallianwallah Bagh.

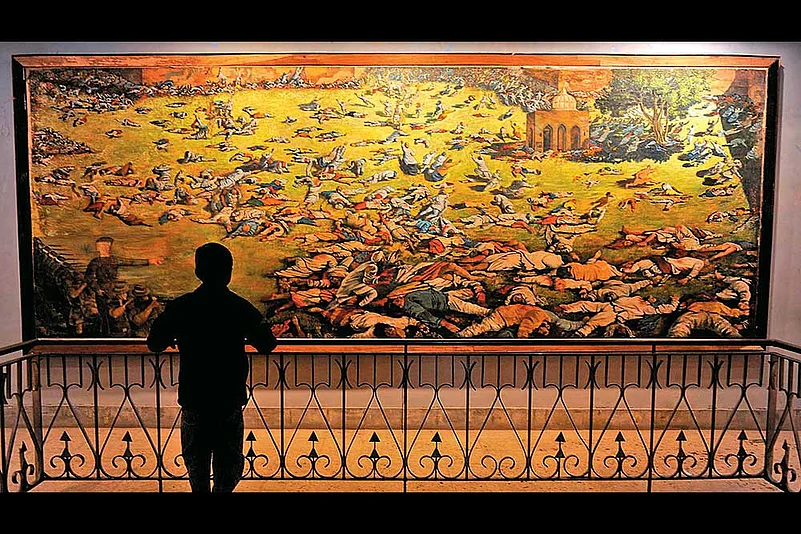

It seemed that Jarnel Dyer had gone with an armed force to a walled enclosure called Jallianwallah Bagh, where there was a meeting being held, and, without giving any warning, he had ordered the platoon to shoot, killing hundreds and leaving the dead and wounded to shriek and weep, plastered with their own blood.

Some people said that Jarnel Dyer and the deputy commissioner had gone around the town and announced, by beat of drum, that no meeting would be allowed, but others said that there had been no warning heard in our vicinity.

“These White Sahibs think that if you spit in the ordinary way you are insulting them,” said uncle Dev Dutt. “And if you shout for freedom, you are uttering ‘insulting cries’. Why, they are alleging that the peasants of the surrounding areas have been pouring into the town to take part in an organised revolt, while you know, and everyone knows, that the peasants come for the Baisakhi fair to the Durbar Sahib at this time of the year.... The city had been so calm and peaceful—and as a reward we get this!’

“Some of the boys of our lane had gone to the meeting,” said Ananta. “Please come with us and see who is dead and who is wounded.”

Whereupon a few of the older coppersmiths, Moti, son of Acharya, Viroo, Sadanand, Ananta and uncle Dev Dutt proceeded towards the Jallianwallah Bagh. I felt excited, with a watchwild look in my eyes, and a suppressed cry of fear, for these people who had gone out to investigate.

“I was right,” mother said, “wasn’t I, not to let you go out of the house in these terrible days. The Sahibs—they have raised their heads to the skies!”

As the news of massacre had come just before halflight, the gloom in our lane mixed, as it always was, with the smoke of hearth fires, thickened into my own hallucinations of the ghosts of those who had been shot dead. I asked mother what would happen to their souls. And she said they would be wandering about, angry ghosts on earth, because they had died such cruel deaths and they would haunt the streets they came from. And, to be sure, I could sense the conjured auras rise before my fevered eyes. The wails of women mourning in the lanes, for those who had not yet returned, made the incantations of the devout ring eerily in the hour of grief. My eyes were bloodshot. My soul was on fire. The wound hurt as though, instead of healing, it had opened up and became raw again.

Underneath the misery of stifled feelings in my throat, I felt the satisfaction of being proved right by the shooting in Jallianwallah Bagh. For no longer was I alone and isolated as a victim. And the stain on the respectability of my family, through having spent a night in police custody and got seven stripes, became a kind of invisible sign of merit. I despised myself for arguing like this, but, somehow, my reasoning made me belong to the other people in the crisis. To be sure, uncle Dev Dutt was approached to get me to show the marks on my back at a meeting in his house the next day. Mother forbade this, saying that the boy had just wandered away and been caught and was not to be made into a hero. I knew she said this partly because she did not want me to be spoilt by the notoriety and partly because she did not want father to lose his position in the army if the exhibition of my bruises came to the attention of many people or the newspapers. Instead she got Ganesh to write to father, asking him to send an orderly escort for us to be removed from this ‘hell’ to Jhelum cantonment.

The earth was peopled by more disembodied spirits of vapour before my eyes, and my pallid lips twitched with incoherent words, even as I clung to mother during the dreams of the nights. But I was no longer frightened of ghosts. The mad rage in me had absorbed their wails.

(This is an extract from the novel Morning Face, by Mulk Raj Anand, first published in 1968 by Kutub Popular)