William Dalrymple has justifiably acquired a global reputation as the most widely read chronicler of British India today. His popular histories, notably White Mughals, The Last Mughal, and Return of a King, as well as the co-authored Kohinoor, testify to the 54-year-old Scot’s focus, erudition, and narrative drive. With The Anarchy, which traces the irresistible rise of the British East India Company from its origins as a trading concern in 1600 to the ruler of all India two centuries later, he cements his reputation with a detailed, compelling account of a story no Indian should forget.

At the beginning of the 18th century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 per cent, as large as all of Europe put together. (In 1700, Aurangzeb’s treasury raked in £100 million in tax revenues alone, more than all the crowned heads of Europe combined.) By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 per cent. The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India.

The Mughal empire stretched from Kabul to the eastern extremities of Bengal, and from Kashmir in the north to Karnataka in the south. William Dalrymple depicts the anarchy that occurred as it disintegrated—the savage incursion of the Persian Nadir Shah, who plundered Delhi in 1739, the raids by the Marathas and the growing assertiveness of autonomous satraps and princelings in far-flung reaches of the empire, who ran their own fiefdoms as semi-independent kingdoms owing only nominal allegiance to Delhi.

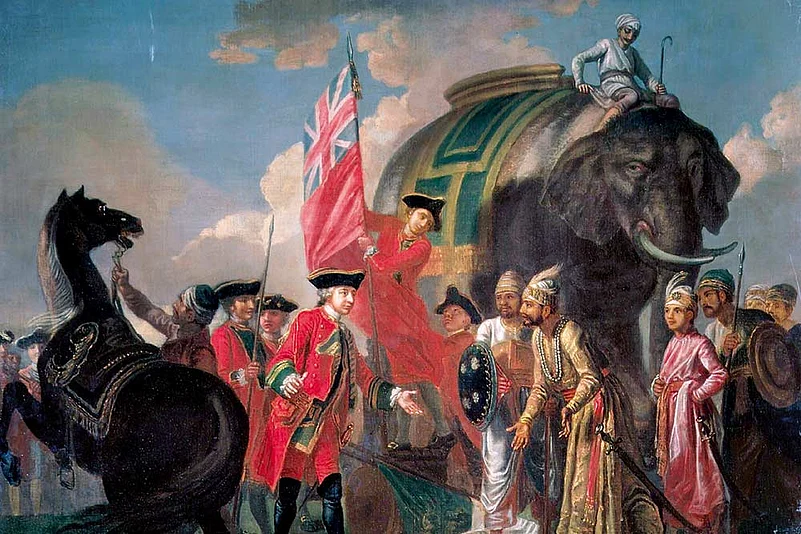

In August 1765, the young and weakened Mughal emperor, Shah Alam II, was browbeaten into issuing an imperial edict whereby his own revenue officials in the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa were replaced with those of the Company. An international corporation with its own private army—and princes paying deference to it—had now officially become a revenue-collecting enterprise. India would never be the same again.

Taking advantage of the collapse of the Mughal empire and the rise of a number of warring principalities contending for authority across 18th-century India, the British subjugated a vast land through the power of their artillery (the Brown Bess muskets, in particular), the superiority of their military techniques and the cynicism of their amorality. They displaced nawabs and maharajas for a price, emptied their treasuries as it pleased them and took over their states through various ever-more cynical and extortionate methods.

“What honour is left to us?,” Dalrymple quotes a Mughal official named Narayan Singh asking after 1765, “when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?” But honour was an irrelevant concern for his emperor’s ‘faithful servants and sincere well-wishers’. The Company—“the most advanced capitalist organisation in the world,” Dalrymple calls it—ran India, and like all companies, it had one principal concern, shared by its capitalist overlords in London: the bottom line.

In the hundred years after Plassey, the East India Company, with an army of 2,60,000 men at the start of the 19th century and the backing of the British government and parliament (many MPs were shareholders in the enterprise), extended its control over most of India. The British government and political establishment was entirely complicit in the venture, accrediting the Company’s officials and seeing its work as an extension of British policy in defence of national interests; more cynically, it “was a matter of personal concern for many MPs, as a large number had invested their savings in East India stock”. It was a startling and unrivalled example of what, in a later era, Marxists in the 1970s grimly foretold for the world: rule of, by and for, a multinational corporation.

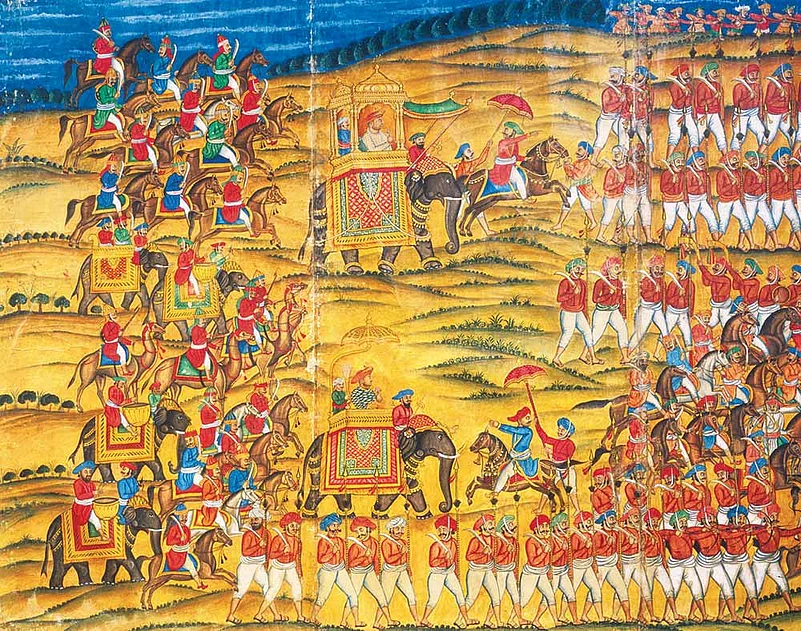

Tipu Sultan rides to battle. His fall in 1799 was a major victory for the British.

This is the story Dalrymple tells in his magisterial study, and he tells it exceedingly well, with a command of both the sweeping historical summary and the telling anecdote. His style is fluent and compelling, with only the occasional indulgence—“buttery Elizabethan burghers, their white-bearded faces nestling in a feathery tangle of cambric ruffs”. As a historian, he is sure-footed in his command of his material, confident in his assessments, and largely even-handed. The vast amounts of research peppering his notes and bibliography are worn lightly, and leavened by a fondness for gossipy detail: Dalrymple recounts, for instance, that Company grandee Francis Day established Madras at a location chosen only because it was convenient for him to pursue his romantic assignations with a Tamil lady whose village lay just inland from the new British settlement. A throwaway line mentions “the Raja from Tipperary”, a former Irish cabin-boy turned artillery captain; another footnote narrates the story of Capt James Stewart, killed by a sniper in 1799, whose head is still worshipped at a shrine in the local police station. (No oddity escapes the popular historian’s questing eye.)

Dalrymple is a story-teller, not a polemicist; he lays out his narrative in unsparing detail and leaves the readers to draw their own conclusions. In his recounting of events and motivations he skilfully depicts both the chaos and anarchy that India was enveloped in when the British seized their chance, and the cynicism and avarice that propelled most British actions. What is clear, though, from his extensive reading of contemporary records, accounts and correspondence, that the self-serving myth that the British acquired India in a “fit of absent-mindedness”, is utterly false. The British knew what they were doing at every stage, even when luck, weather and happenstance enabled some of their more unlikely successes.

At the same time, he gives us enough information to read between the lines. We are told, for instance, that the British in 1757 made no effort to save the ‘Black Town’ in Calcutta, where their ‘native’ servants lived, from the depredations of the invading Siraj-ud-Daula, nor to offer shelter in the fort to the terrified victims of the marauders: “No wonder, then, that…all the Indian support staff…defected, leaving the garrison without lascars to pull the guns, coolies to carry shot and powder, carpenters to build batteries and repair the gun carriages, or even cooks to feed the militia.” The words ‘racism’ or ‘apartheid’ nowhere occur in this volume, but the intelligent reader will have no difficulty finding the seeds of both in the early days of the empire’s establishment.

It is hard to disagree with most of Dalrymple’s assessments, whether of the legacy of the Emperor Aurangzeb, the role of the opportunistic Indian merchant bankers—the Jagat Seths, who dealt at their peak with more funds than the Bank of England–in the triumph of the East India Company (they financed the Company’s overthrow of rulers they saw as hostile to their trading interests and profits), or of the weaknesses and faults (and sheer cruelty) of many of the Indian princes whom the British defeated. He comes to even-handed conclusions on such contentious issues as the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’ (a tale much exaggerated in the recounting by motivated mythologisers) or the good qualities of the syncretic “connoisseur and intellectual” Tipu Sultan (now unjustly demonised by India’s current ruling establishment as an Islamic fanatic). He is also unsparing in detailing how the takeover of Bengal by the Company was an “unmitigated catastrophe” for the Bengali people, a third of whom perished soon after in a famine caused in 1770 and prolonged by British policy, described in painstaking (and painful) detail. (In Macaulay’s words, the Company looked on Bengal as “a buccaneer would look on a galleon”). Somewhat more contentiously, Dalrymple is kind to Warren Hastings, subject of the most famous impeachment trial in British parliamentary history, which gets short shrift in just five pages.

When Lord Wellesley, whose reputation Dalrymple does much to restore, heard of the death of the Company’s last major adversary, Tipu Sultan, he raised a toast: “I drink to the corpse of India”. The corpse of India did rise in 1857, against the Company that mutilated it, drained it of everything it possessed and then stitched it back together again. The crown then took over the Raj; the East India Company, shorn of its grandest possession, wound up in 1874. A few years ago, its brand name was acquired by a Gujarati Indian businessman who uses it to sell “condiments and fine foods” from a showroom in London’s West End.

The Anarchy ends on a minatory note, finding parallels between today’s global power politics, with the contemporary dominance of “multinational finance systems and global markets”, and the overweening power of the East India Company, whose story “has never been more current”. That is a departure from the historian’s engaging narrative and seems to be a hastily tacked-on ‘current affairs’ justification for the book. Dalrymple should have dropped it. The Anarchy is a lucidly written, knowledgeable and gripping work of narrative history; it doesn’t need the lecture. It is well worth reading in its own right.