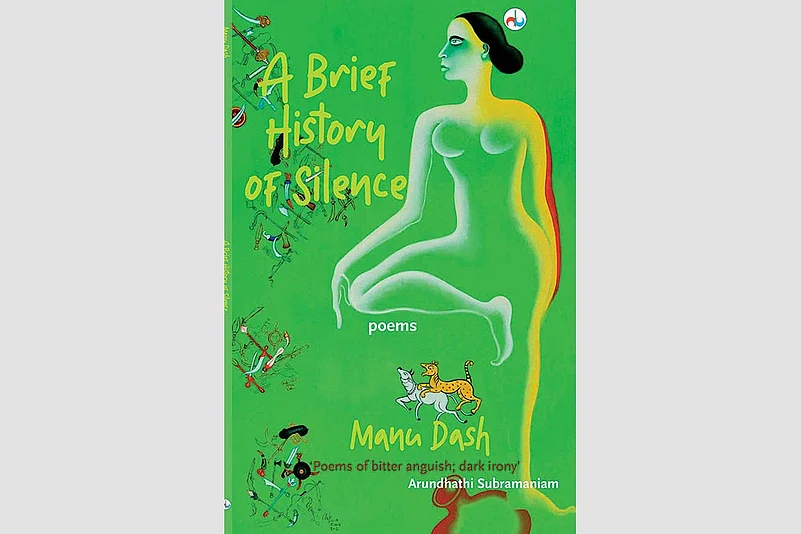

Just because someone brings out his debut collection of poems at the ripe age of 62 doesn’t mean that he is a novice. All these years Manu Dash has been busy publishing other poets and writers. Four decades of passion for poetry has issued forth in A Brief History of Silence. Manu dons many hats: story-teller, anthologist, editor, publisher, litfest curator. But essentially he’s a poet, imbued with a typical Odia coyness that underplays his poetic instincts. Reading Manu’s poems, one feels an eerie silence which is no less eloquent in that those voices echo within one’s soul. One has to attune oneself to the peculiar rhythm of the alphabet of silence: “In the mountain curve, / A river was busy composing music”.

He puts poetry to good use as an antidote to our collective sense of guilt, helplessness and despair. His tone is contemplative, laced with a tinge of fatalistic resignation: “History sits like an albatross /around the neck. /The wind is the lone carrier of songs /of the dead”. In such tumultuous hours, for the poet, even god doesn’t come as a solace as he is “indecisive and unfeeling”. The poet sombrely confesses that “Evening is meant for rumination/over the day’s failures”. In such godless times, the poet rues: “All have forgotten/ I too have a face of my own/ and when I exhibit it, they fail to recognise me”.

Manu’s poetic imagination hovers around places like Konark, Puri, Bhubaneswar, river Daya…, and recurring images of rain, temple, death and decay remind us of the oeuvre of Jayanta Mahapatra. Manu eschews literary sophistry; and his exploration of his environs with ceaseless ‘wonder’ yields rich dividends: “Summer has overstayed/ like an unwelcome guest.... The old astrologer smiles on TV/ advising us to watch and wait.”

The poems also do not flog the old chestnuts of angst, ennui, or existential limbo, and are without abstractions in imagery or symbolism. He picks his themes from life felt or seen intimately: “The decomposing newspaper sobs/ measuring the long day”. The poet hears “The whining of the bulldozer clearing the debris” and ‘hymns’ that goats and roosters recite. He believes that the ‘obvious’, too, needs to be shown: “How much of plastic/ do the cows of our times consume?” Imbued with an ‘old world’ charm, he plays around the erotic and sensual once a while: “The beauty of words/ like the breast of a lady,/ less revealed more concealed/ in the cave of her mind.”

Reading Manu’s poems is like visiting a black and white photo gallery where the proportion of darkness to light reveals a ‘surly, grey’ reality. Although writing political poems is not his forte, the saving grace here is Irom Chanu Sharmila. A set of seven artistically imagined questions build up the structure of this short, powerful poem: “What contour does iron take/when it starts melting?/ What music does it produce/ when love smells the body?” Never ostentatious, what captivates the reader is a certain earthiness, a lilting voice; a voice that sits light as feather on their shoulders.

(Panda is a bilingual poet and critic)