It is nearly 75 years since Partition--some three generations. The first generation, from the ’40s to the ’60s, was brought up in the shadow of the horrors of Partition and the ‘animosity’ that brought about the vivisection. The second generation, from the ’60s to the ’80s, was brought up in the period that witnessed the second Partition of the sub-continent, with the liberation of Bangladesh, the attempted reconciliation with rump Pakistan through the Simla Agreement and the unravelling of bilateralism. The third generation runs roughly from Kargil (1999) to the present.

Pallavi Raghavan belongs to the third generation and, through this little gem of a book, has returned us to the all-but-forgotten first generation period when, notwithstanding all the hatred and vicious violence that caused and accompanied Partition, the relationship between the two Dominions was characterised by a “dense set of bilateral negotiations” (p.17) that that are difficult to credit in the present age of bitter stand-off.

That was because the principal personalities—politicians or bureaucrats—knew and had worked with each other. Thus, both H.M. Patel and Chaudhry Muhammad Ali, who were representatives of their respective countries on the Steering Committee of the Partition Council, functioned in relative cordiality “against the backdrop of savage rioting and bitter political animosity” (p.24). Again, Sri Prakasa, the first Indian High Commissioner to Karachi, then the capital of Pakistan, and Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, the first Minister for Minority Welfare in Pakistan, “had many commonalities. Both were from the United Provinces and had cut their teeth in the agitations of the 1920s and ’30s…and could assert a reasonable degree of proximity to Nehru and Jinnah respectively” (p.40). And the two prime ministers, Nehru and Liaquat Ali, knew each other well and had no difficulty in meeting frequently in the aftermath of Partition and right up to the 1950 Nehru-Liaquat Pact. This illustrates Raghavan’s basic thesis that “many of the questions of state-making in India and Pakistan had to be done in consultation with each other” (p.13) to attain the “shared goal of finalising the partition” (p.9).

She takes us through the bilateral negotiations that led to “Islands of Agreement” (p.16), beginning with the joint decision to dissolve the feckless Punjab Boundary Force that had done next to nothing to mitigate the ghastly massacre of migrants (pp. 31-34); the resolution of the vexed question of abducted women, running to tens of thousands on either side through “an inter-Dominion agreement” which established a “joint machinery for the recovery of abducted women on either side of the Punjab” (pp. 34-39); the aching problems of resettling and rehabilitating refugees and the related issues of “evacuee property”—to which Raghavan devotes a chapter (pp. 74-98)—through evacuee property conferences that stretched from 1947 to 1953 (p.79) and led to India and Pakistan “vouchsafing their claim to statehood vis-à-vis one another” and “consolidating the effects of partition” (p.98).

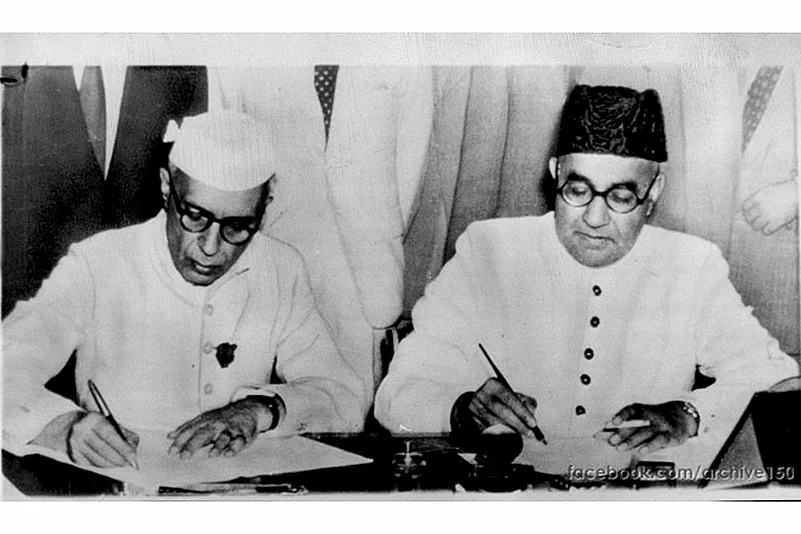

The over-arching question left by Partition was the need to define national responsibilities for the religious minorities in both states. In the west it had been ‘jhatka’: within weeks millions had been driven across divided Punjab. The ethnic cleansing was almost complete. In the east, it was ‘halal’: the bleeding went on for at least three years after Partition, picking up momentum in September 1949 and reaching such a pitch by February 1950 that Liaquat wrote to Nehru suggesting that a declaration be made “from the two governments that all possible steps shall be taken to rehabilitate the minorities in their homes and to see that they are given full protection of life and property.” (p.65). This was the origin of the Nehru-Liaquat Pact of April 1950 that engaged both governments to “ensure to the minorities, throughout its territory, complete equality of citizenship, irrespective of religion, a full sense of security in respect of life, culture, property and personal honour, freedom of movement within each country and freedom of occupation, speech and worship, subject to law and morality”. (p.65)

There are five points of note in this unique international agreement. First, it binds the two governments bilaterally tounilaterally ensure the rights of minorities in their respective territories. I cannot recall a single other instance in international diplomacy of such an agreement. Second, as Pakistan was still to formulate its Constitution, the rights to be guaranteed are drawn from the Indian Constitution without embarrassment to either party. Third, although inter-Dominion conferences on refugees and minorities had been going on since January 1948 at the civil servant level, and even resulted in joint machinery for resolving issues, it did not succeed satisfactorily and so top political leadership had to take matters in hand. Fourth, it was a Pakistani initiative, not an Indian one. Give them credit where credit is due. Yet, fifth, the pact’s foundational value is that it embodied Nehru’s answer to the “constant cry for retaliation and vicarious punishment of Muslims, because the Pakistanis punish Hindus. That argument does not appeal to me in the slightest. I am sure that this policy of retaliation and vicarious punishment will ruin India as well as Pakistan.” (p.109).

Raghavan emphasises that “the only way that both governments could assert their final separation from one another had to be through a process that synchronised and calibrated their dialogues about the position of minorities across the border”. (p.66). The Pact, she notes, was “nothing less than a signed statement by two prime ministers about the nature of their policies to their minorities being of concern to the other” (p.67). They were “giving a viable and practicable shape to the meaning of partition” and “seeking a collaborative arrangement…in the expectation that some of the dilemmas in (the) wake (of partition) would be mutually reconciled” so that they could “evolve structures of statehood and its demands on mutually constituted terms” (p.71).

Raghavan’s chapter (pp.99-16) on the No War Pact shows how through intensive interaction at both diplomatic and political level, it was possible to consolidate the statehood of both countries even when the outcome amounted to no more than an agreement to disagree, with India being all for a simple but clear commitment to not going to war on any unresolved issue, and Pakistan being ready to go along only if all these outstanding issues were listed.

Perhaps the principal outstanding issue, apart from the question of the minorities, was the sharing of the Indus waters. Raghavan sets the stage by pointing out that this was an issue that long pre-dated Partition and went back to the 1920s and 1930s when “complaints had been made to the (Imperial) Government of India by the provincial governments of Sindh, Patiala and Punjab”. So, in the immediate aftermath of Partition, a Standstill Agreement was put in place and an Arbitral Tribunal established. Although Raghavan does not mention this, the West Punjab government failed to seek an extension of term for the Tribunal before the Standstill Agreement lapsed on 31 March. So, from April 1 “India unilaterally cut off the water supplies to Pakistan” (p.121) [Actually, it was not ‘India’ but the Government of (East) Punjab that egregiously did so without consulting the central government]. Instead of refusing to engage, as is the practice now, a negotiating team from Pakistan that included the finance minister and two senior West Punjab ministers was despatched to work out an interim agreement, signed on May 4, 1948, defusing, at least for a while, an issue of the highest concern in both Punjabs (p.121). In September 1948, chief engineers of the two Punjabs met at Wagah to “further elaborate the arrangements by which irrigation supplies should be distributed” (p.121). Numerous bilateral meetings, largely technical but also at high political level (Zafrullah Khan and Gopalaswamy Ayyangar), and some convened by the World Bank, followed but it was not till more than a decade later, in 1960, that the Indus Waters Treaty was signed, with India retaining absolute control over the headwaters, Pakistan securing an assured supply of water, and the World Bank providing funding to building the alternative irrigation arrangements in Pakistan and the Bhakra-Nangal dams in India. Not all the wars that have happened since between India and Pakistan have been able to cause the abrogation of this mutually negotiated Treaty. It shows what persistence and patience can do. As Ayub Khan, as cited by Raghavan, wrote in his memoirs, “The only sensible thing to do was to try and get a settlement, even though it might be second best, because if we did not, we stood to lose everything” (p.136). That unexpected wisdom applies to every outstanding dispute between India and Pakistan.

While affirming that the treaty certainly confirmed the finality of Partition and consolidated the statehood of the two nations, surely Raghavan is right in concluding that there is a “deeper significance” to the “hectic cooperation and dialogue” that characterised the first five years of the separate existence of India and Pakistan: that the “best remedy for the situation called for a series of detailed negotiations…and can also serve as a relevant guide to the maze of India-Pakistan relations today” (pp. 185-186). That is why I keep maintaining that the only way forward in our relationship is through “uninterrupted and uninterruptible dialogue”.