Readers of a certain vintage, (most would be above 80 now) awaited every new offering from Hemendra Kumar Roy with bated breath in their boyhood. Jawker Dhan, or its sequel, the adventures of Jayanta, Manik, the bumbling Bimal, held them in thrall. Exotic locales, boisterous boyish fun, raucous humour, scientific detail, detection were all grist for the mill of this prolific writer with an enviable sense of pace. There was also a thrilling sense of menace in an age before they could be conjured on celluloid by special effects. Bollywood and Tollywood both used him; his marvelous sense of detail must have made it easy for film adaptations.

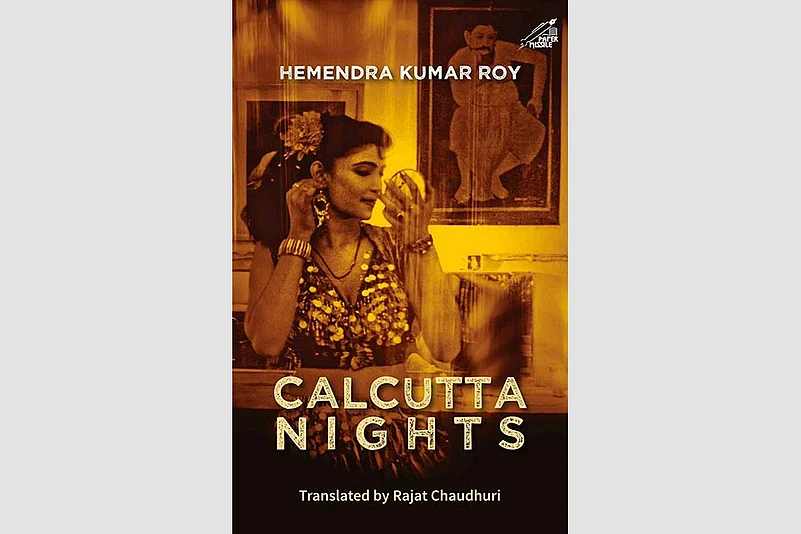

Many of Hemendra Kumar’s works are non-fictional adult writings. The highly appropriate cover design by Pinaki De suggests that Calcutta Nights is not kid-lit. Its Bengali predecessor is the amazing Hutom Pyanchar Naksha (1861), the Sketches of Hutom the Owl, itself a denizen of the night, by Kaliprasanna Sinha. In the persona and using the nom de plume of Meghnad Dutta, Hemendra Kumar tells you that things haven’t changed much since then.

The selection of that name seems to be deliberate. The mythological Meghnad was the loner, ready to take on the forces of darkness on his own, and Dutta was the surname of Michael Madhusudan, who wrote the alternative epic with Meghnad as hero, pulling no punches with the Ramayana’s more traditional heroes.

The setting is Pathuriaghata, the author’s own neighbourhood, the happening part of the old city, now the itinerary of heritage walks, which has two Tagore palaces, grand buildings like the Marble Palace of the Mullicks, the old China Town, the jatra centre of Calcutta, Nakhoda Mosque, old theatres and the many lanes and bylanes, some of which lead to the crematorium and the Hooghly. Famously hoary restaurants, like the iconic Royal India, abound too. Even now, if one gets lost in the lanes, one hears a cosmopolitan babel of languages and dialects: Bengali, the Hindi of Marwaris or Biharis, Urdu, Hindusthani, Chinese. When people in the area want to communicate secrets they will speak in a language entirely incomprehensible to the outsider.

The sense of menace takes on a more sinister tone when Hemendra Kumar explores the area in the 1920s--with its drug trade, the haunts and mansions of babus who visit brothels and the abodes of baijis and nautch girls, as murder and mayhem place the explorer in situations from which he escapes with ingenuity and/or local help. As with the author of Hutom Pyanchar Naksha, the Babu is his pet hate and object of ridicule, the ‘hathat (sudden) babu’, the nouveau riche one, particularly so.

In the preface, Hemendra Kumar states his objective, which is moral, that is, not prurient. He claims to address a target audience of adult males to warn them of the snares of the night for themselves and for the sons they allow to roam the streets. The work is thus a strongly male one.

The night gives way to an even more menacing dawn when the zamindar’s widow appears in a carriage with retinue in tow, prowling for youthful partners as she goes to take her bath in the sacred river. The Kalighat Temple itself is full of shady characters.

Rajat Chaudhuri’s translation is flawless. The retention of an occasional word in the original Bangla helps to retain the racy flavour of the prose. Pinaki De’s ‘patachitra’ type period illustrations punctuate the narrative, adding period heft as well as amusement.

Adventurer or moralist, voyeur or social reformer, Hemendra Kumar moves effortlessly between roles, sometimes recalling the writings of the 19th century Victorian Chartist G.W.M. Reynolds, who never allowed a bourgeois sense of propriety to prevent him from presenting the unadorned truths of the urban landscape of sin. I understand his writings were very popular in Hemendra Kumar’s time, in the original, in translation and in adaptation. The wanderings of Arthur Munby with his strange sexual preferences also come to mind, as does the highly orientalist Kipling’s sauntering through the contiguous area of Bowbazar in his City of Dreadful Night (1888).

Despite some touches of misogyny, I thoroughly enjoyed the perambulations of a nighttime flaneur in sin-filled 1920s Calcutta, during a time when even venturing outside the house during the day seems only just this side of the frankly criminal.