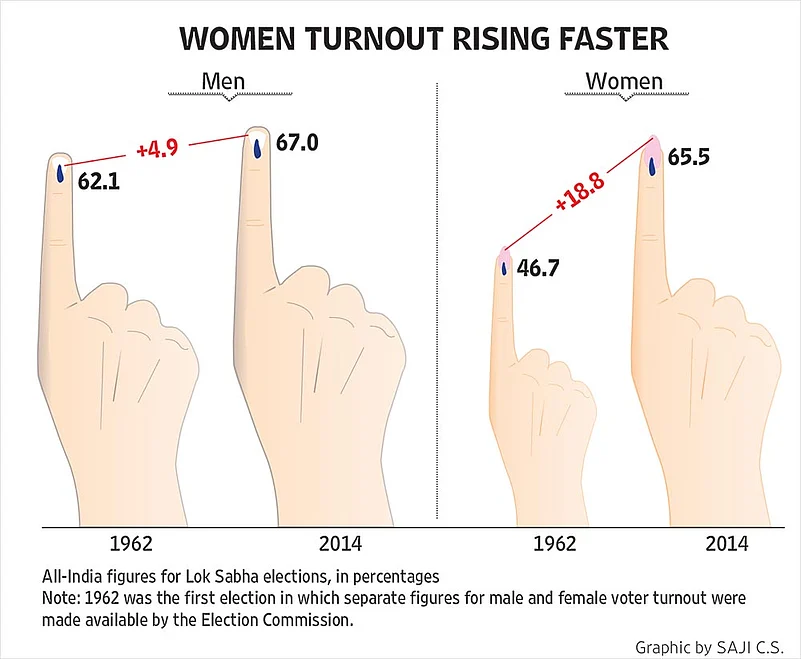

Perhaps the most heartening sight while travelling around the country during elections is long queues of women outside polling booths, waiting to vote. These lines are often longer than the separate queues for men. The current high level of women’s participation has been a major development in India’s democracy. In 1962, the turnout of women was only 47 per cent (of the total female electorate), yet by 2014, it had shot up to 66 per cent—up by nearly 19 percentage points. On the other hand, men’s turnout grew by only 5 per cent over the same period.

This differential growth rate in turnout has meant that, over time, women’s turnout in Lok Sabha elections has almost caught up with and is likely to overtake that of men soon, perhaps even as soon as the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. In 1962, women’s turnout was 15 per cent lower than men’s turnout; but by 2014, women’s turnout had almost reached parity with men, short by only 1.5 per cent. This represents a remarkable, if belated, turnaround over the last half-century.

As an aside, this very strong statement by women on ensuring a greater say in the democratic process in India almost parallels the significant finding by Imperial College, London, that the height of women in India has grown significantly more than that of men: an average Indian woman’s height has gone up by 4.9 cm as against an increase of 2.9 cm in an average Indian man’s height over the past century. Of course, women are still, on average, not as tall as men: 152.4 cm (5 ft) vs 165 cm (5 ft 4.9 inches), but women are catching up!

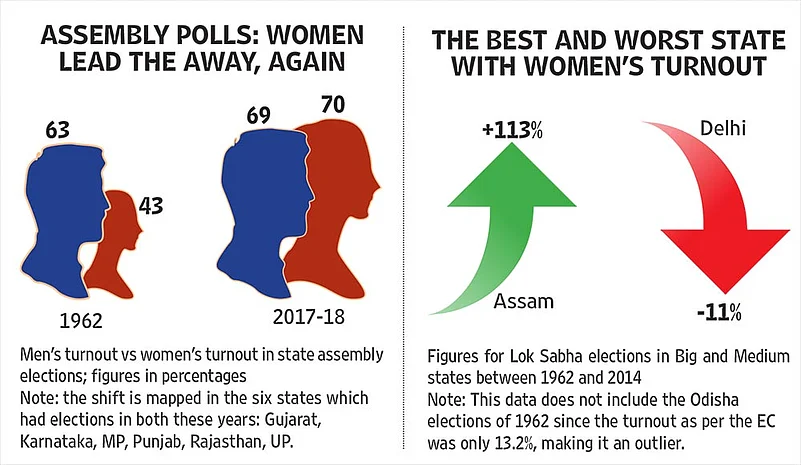

The rise of women voter turnout is even more pronounced in state assembly elections. In fact, for the first time in India’s electoral history, women’s turnout was higher than that of men in the state assembly elections of 2017-18. From being well behind men for 55 years—in 1962, women’s turnout (in assembly elections) was as much as 20 per cent below that of men—they have finally overtaken men. This represents an inflection point when annual quantitative improvements have finally led to a qualitative change in the gender underpinning of India’s democracy. This speaks of social churn, and it is not surprising that today political parties focus much more on women’s issues during their campaigns than ever before.

For this turnaround to happen required a remarkable growth in women’s turnout compared with men. It shot up by almost 27 percentage points in assembly polls held between 1962 and 2018 as against men’s turnout, which increased by only 7 percentage points in the same five and a half decades till 2017–2018.

Even if, unlike state assembly elections, the overall women’s turnout in Lok Sabha elections is still slightly behind men, there are some states in which women’s turnout is noticeably higher than that of men. Interestingly, two states from the east of India, Bihar and Odisha, top this list. On the other hand, Madhya Pradesh is one of the two worst-performing states in which women’s turnout lags far behind men, by 10 per cent—and not far behind, further west, is Gujarat.

However, even for Lok Sabha elections, this impressive increase in women’s turnout has not been uniform across all states. In fact, it has seen a worrying decline in some states—the worst state is Delhi. At the other end of the spectrum are states in eastern India such as Assam—which have shown the most remarkable and encouraging rise in women’s participation in elections.

For those who believe that India is a ‘male-dominated’ society, the responses we got in our pilot surveys would be an eye-opener. Whenever we questioned women on whether they voted for the party that their husbands told them to vote for, the women’s responses were predominantly to laugh at us, and to treat the question with derision. They would often say: ‘He may think that I listen to him about who to vote for, that’s in his dreams—I vote for exactly who I want to vote for.’ We heard this clear statement of independence repeatedly in election after election, state after state at election time over the last decade or so. In a survey by the CSDS for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, 70 per cent of women voters said they did not consult their husbands on who to vote for. Our estimate is that the percentage of independent-minded women voters could be significantly higher than is publicly admitted to a fieldworker. Women voters who make up their own mind could now be at least as high as 80 per cent.

It’s not surprising, given how men and women usually vote independently of one another, that opinion polls always tend to show different levels of voting intentions between men and women respondents. The differential can be as high as 20 per cent for a particular party. It’s clear that in India, women are a distinct and independent ‘votebank’, on which political parties have already begun to focus in order to win elections. This involves meeting different demands and using different messages.

Women’s turnout also impacts political parties in different ways. For example, the BJP’s support amongst women has tended to be lower than among men. In the last Lok Sabha elections of 2014, the BJP + Allies (NDA) had a lead over the Congress + Allies (UPA) of 19 per cent amongst men and a much smaller lead of 9 per cent amongst women.

To emphasise how important the male vote is to the NDA: if no women, only men had voted in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the NDA would have won by an enormous landslide with 376 seats. However, if no men, only women had voted, the NDA would have won 265 seats—which would have been seven seats short of the majority mark.

Missing Women Voters

Perhaps, the most distressing aspect of our current election system is that millions of women in India have not been registered to vote even though they are over eighteen years old and eligible.

The disenfranchisement of women voters is hopefully a result of mere inefficiency, not quite in the same league as the ‘dark arts’ of voter suppression around the world. However, it is a deeply worrying phenomenon of our electoral system.

The data points towards a major problem: the most reliable measure of population, the 2011 census, suggests that by 2019, the total population of women in India will be 97.2 per cent of the total men’s population. Consequently, it is only to be expected that the total electorate of women voters should be the same percentage of the total male electorate—or at least very close to this figure. However, the Election Commission data for 2019 states that women voters are only 92.7 per cent of male voters.

This difference between what it should be, 97.2 per cent, and what it is in reality, 92.7 per cent, indicates that there is a 4.5 per cent shortfall of women voters. Why is this? And is it significant? It is now clear from past census figures and Election Commission data that this under-representation of women has occurred election after election, decade after decade. The worst disenfranchisement of women was in the 2014 Lok Sabha election when 23.4 million women were denied their right to vote.

In fact, while 4.5 per cent may seem a small percentage, when converted into actual numbers of women, the scenario is staggering. The 4.5 per cent of missing women translate into as many as 21 million women denied their constitutional right to vote simply because their names are not registered in voter lists across the country.

An indication of how large this figure of 21 million missing women, if you were to consider this, is that it is equivalent to every single woman in any one of the following states not being allowed to vote: Jharkhand, Haryana, Telangana, Kerala or Chhattisgarh!

Or even worse: 21 million missing women translates into 38,000 missing women voters in every constituency in India on an average. There are a large number of Lok Sabha constituencies—more than one in every five seats—that are won or lost by a margin of less than 38,000 votes.

The estimate of 21 million missing women voters is based on the percentage/ratio of women to men in the electoral rolls compared with the percentage/ratio in the census. Alternatively, if we do not use ratios but compute the absolute numbers of women according to the census, compared with the absolute numbers in the electoral rolls, the number of missing women is even higher, at a staggering 28 million missing women voters.

The large number of women voters missing from the electoral rolls has another implication: it suggests that the total electorate in India should be above the official 895 million, perhaps even more than 915 million.

Officials readying EVMs and other material before an election in Calcutta.

The Election Commission cannot be blamed for this massive failure. On the contrary, this state of affairs prevails in spite of the huge effort they make year after year to enrol women voters, with a range of outreach programmes targeted specially at women.

It is a result of a combination of social and political factors and what is worrying is that it is worsening over time. There are major biases in the extent of missing women between regions, with some states having a much higher level of disenfranchised women than others.

In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the top three states which will have the largest number of women who are not registered despite being eligible voters are Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan. These three states alone will account for over 10 million of the 21 million missing women voters in 2019.

It is shocking that in Uttar Pradesh, 85,000 women voters on an average will be deprived of the right to vote in every single constituency.

Moreover, among the bigger states, those which have the best record with the lowest under-representation of women are from the south of India: Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Even among the small states of India, the two worst offenders are from the Hindi belt: Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

Moving on from absolute numbers of missing women, even if we analyse the percentage of women without their legitimate voting rights, once again the Hindi-belt states are the worst: in UP above 10 per cent of the women will be denied the right to vote, in Rajasthan and Maharashtra, it is over 5 per cent.

These are unacceptably high percentages of disenfranchised women. And once again it is sad to see that even in India’s ‘capital’ state, Delhi, a whopping 16.9 per cent of women who should be allowed to vote will not be able to in 2019.

But there is a silver lining: Many of the smaller states have more registered women voters than men voters. Perhaps, these variations reflect the bigger picture of the vastly different cultural and political attitudes to women in the many regions of our country.

For more on this anomaly, several commentators have analysed the issue of low women’s participation and registration.

An appeal to the Election Commission of India: We need to take note of this shame on India and immediately take steps to rectify it before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

India is facing an extraordinary situation that is terribly unfair to the women of India—21 million women who are entitled to vote will be denied the right to do so because their names are not on the voters’ list.

There may not be enough time to rectify the voters’ electoral rolls before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. In view of this, the rule should now be: Any woman who comes to a polling station and wants to cast her vote, and can prove she is over eighteen years old, must be allowed to vote.

End of Booth-Capturing

We are now firmly in the era of India’s innovative electronic voting machines (EVMs). First introduced way back in 1982 and 1983 as a test, they are now used universally in Indian elections.

India’s electronic voting machines are unique—and ideal for Indian voting conditions. First, and most important, Indian EVMs are not connected to the internet or to any wider cloud or network. They are stand-alone machines that have no Wi-Fi or Bluetooth capabilities. (This is a major difference between India’s EVMs and those voting booths in the USA that have electronic voting, where connection to the internet can leave them vulnerable to hacking). To cast a vote in an Indian EVM simply means pressing a button—there is, of course, one button against each candidate, name and party symbol—and the votes cast are stored inside each EVM. Party symbols are used rather than party names, to take account of illiteracy.

The only way to access the number of votes stored in each EVM is to break open the seal which keeps each EVM secure. The seal can only be broken by an Election Commission official in the presence of representatives of all the candidates—and with all parties looking on, hawk-eyed. If any EVM’s seal is found already broken, the Election Commission announces repolling in the relevant polling booths. In any case, it is virtually impossible to secretly break the seal of any EVM, as every move an EVM makes, from being set up in a polling station on voting day, through to being transported at the end of voting into a locked room, and then to finally being moved to the counting centre only on counting day, is watched and the process guarded by representatives of all parties.

There has been a great deal of criticism of EVMs—inevitably from the party (or parties) that has (or have) lost an election. Most of the criticism of EVMs appears to stem from a knee-jerk mistrust of technology.

Distrust of voting systems happens all over the world. In the 2016 British referendum on leaving the European Union, for instance, campaigners for ‘Leave Europe’ expected to lose in the contest by paper ballot. So in the run-up to polling day, they promoted the widespread conspiracy theory that pencils were being handed out at polling stations so that millions of votes could be erased by the government, and for that reason, they promoted the hashtag ‘#UsePens’ on social media, encouraging voters to bring their own pens to stop their vote from being erased. This was, of course, ridiculous. And when the ‘Leave’ campaign unexpectedly won, nothing more was said about ‘#UsePens’.

The authors have studied and analysed EVMs across India first-hand for years, ever since they were first introduced; and we feel completely confident that they are tamper- and hack-proof, for the following reasons:

- We are convinced that since EVMs are not connected to the internet and do not have any Wi-Fi or Bluetooth capability, they cannot be ‘hacked’ in the usual technological manner associated with the term ‘hacking’. Our discussions with a large number of technical experts have only reinforced this view.

- What about the possibility that every time a voter presses a button, it always registers as a vote to the Congress or the BJP, no matter who the citizen voted for? This pre-programming could theoretically be done at the manufacturing stage, especially as all manufacturers of EVMs are public sector undertakings, and many argue that they could be under the control of politicians in power.

- Fortunately, there is absolutely no point in pre-programming EVMs to try and ensure that the same party always (or disproportionately) receives votes. The reason is that the sequential order of every party in every constituency depends on the alphabetical order of the candidates’ names. First, all candidates of national parties appear in alphabetical order of their names, followed by those of state parties and then unrecognised parties and Independents. So even if someone successfully tampered with machines to ensure that the party against button 2 would always benefit, there is no guarantee that the EVM-fiddling party will always be at button 2. The list of candidates fighting in each constituency is finalised only about two weeks before the elections (after the last date for the withdrawal of candidate names). By this time all the EVMs have already left the factories and cannot be tampered with. The Election Commission, in fact, takes the additional precaution of random allocation of EVMs to constituencies only a few days before the polls.

- The biggest advantage of EVMs replacing ballot papers is that it has meant the end of the practice of booth-capturing that was so rampant in the old days. Booth-capturing involved a strong-arm method (used mostly by, but not confined to, the ruling party at the time) in which a gang of men from a particular party would take over a polling station, frighten away all the voters, and terrify the Election Commission officials. They would then grab all the ballot papers, stamp each with a cross for their party, stuff the locked ballot boxes, and move on to another polling station, doing the same thing. The phenomenon of booth-capturing reached a high point in which about 4-5 per cent of booths were captured by the ruling party, and a further 2-3 per cent of booths were captured by the opposition parties. The net effect of this meant an advantage to the ruling party of about 2 per cent of the total vote—though a total of 6-7 per cent of polling booths had been corrupted in this way. The biggest losers, of course, were the disenfranchised voters in these areas. We have no way of verifying or providing hard evidence for these percentages—electoral corruption is always hard to provide exact figures for, they are always ‘guesstimates’—but we base it on our questioning of politicians and observing elections over many years.

So why can’t the same thing happen with EVMs? Couldn’t gangs use strong-arm methods to capture them as well, and just keep pressing their party’s button on the machine, before going on to the next polling station? After all, surely pressing buttons is even easier than stamping ballot papers? The reason to be sceptical is that each EVM can record a button being pressed only after every twelve seconds. If buttons are pressed more often, the EVM will not register any vote. In any booth-capture situation, it would take nearly three-and-a-half hours to press the buttons 1,000 times (the typical number of votes for any EVM), and even that assumes the buttons would be pressed rapidly, every twelve seconds exactly. EVMs are simply not a feasible or efficient way of carrying out electoral fraud.

EVMs are also more environment-friendly—they have saved almost a quarter of a million trees from being cut down for the paper needed for ballots in recent Lok Sabha elections, not to mention state assembly and other elections. A rough estimate of the number of trees that have been cut down for Lok Sabha elections alone between 1952 and 1998 (when EVMs began to be widely used) totals about a million. It would have got worse because for every Lok Sabha election today, about a billion ballot papers would need to be cut, printed and kept ready.

The original EVMs did not need any paper at all. However, because of the constant clamour against EVMs, mainly by the losing parties, the Election Commission was forced to make alterations to the EVMs, despite their already being secure. The Election Commission introduced a ‘paper trail’ for every button pressed and vote cast: a ‘touch and feel’ analogue evidence of exactly the same digital event. Every EVM now has a second machine attached which is effectively a printer. Except, this printer (called by the awful name VVPAT, which stands for Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail) is sealed, and has a small window behind which a slip of paper passes for ten seconds, before it falls into a sealed container at the base of the VVPAT (printer).

The small glass window is at the front of the VVPAT, through which voters can ‘see’ the party that they have just voted for, as a confirmation that the EVM has recorded their vote correctly. The nearly billion slips of paper thus generated are seldom, if ever, looked at—only when there’s a dispute is the sealed printer opened and the slips counted.

While the VVPATs have lessened the relentless attack on EVMs, blaming them for an election loss is, unfortunately, still par for the course. As a consequence of the barrage of such attacks at press conferences and across the media, there is sadly little doubt that the voters’ trust in EVMs has suffered, for the wrong reasons.

In conclusion, we believe that EVMs have been and still are one of the finest innovations for Indian elections. In fact, perhaps democracies all across the world could learn some lessons from Indian EVMs: their remoteness from the internet to prevent tampering and their ease of use for illiterate voters are major advantages. If the USA had adopted Indian EVMs, they would have come a long way from ‘pregnant chads’ and ‘hanging chads’—and who knows, Al Gore may have been president!

Specifically, in India’s context, the end of the old scourge of booth-capturing is one of the greatest developments in the maturing of Indian democracy. Unfortunately, it cannot be attributed to an improvement in law and order, or to there being fewer strong-arm tactics used today. Instead, booth-capturing ended primarily because of EVMs. We have no hesitation in concluding that India should not only trust EVMs but should be proud of the innovation and the digital design.

***

Should opinion polls be trusted?

There are likely to be over 100 polls of different types and sizes in the run-up to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Should their forecasts be trusted? The evidence of opinion polling in India, 833 polls over the last forty years, suggests that we should trust our polls, at least most of them. The record shows that most polls get the winner right but are often way off the mark when it comes to forecasting the exact number of seats.

In fact, with the exception of one outlier election, polls have got an impressive 97 per cent strike rate in predicting the winner for Lok Sabha elections. The one time every single poll got its forecast wrong was in the ‘India Shining’ election in 2004 when they said Atal Behari Vajpayee would be re-elected as prime minister and he lost.

***

Who will win the 2019 elections?

The bad news for ruling governments is that the voter is wiser and smarter. Voters throw out all non-performing governments and re-elect governments that have worked and delivered.

A corollary to the end of the pure anti-incumbency era is that in the current fifty:fifty phase of our democracy, the voter has a message for all elected governments: perform or perish.

The voters’ yardstick for ‘performance’ is whether economic growth translates into genuine development on the ground, in their lives and their constituencies.

So elections today are not won simply by flamboyance. The most successful chief ministers over the last twenty years, with high re-election rates, have been low-key, result-oriented leaders like Shivraj Chouhan, Naveen Patnaik, Raman Singh, Manik Sarkar and Sheila Dikshit. All at least three-time winners. Oratory also works as long as it is combined with development as in the case of Narendra Modi when he was chief minister of Gujarat.

.jpg?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)