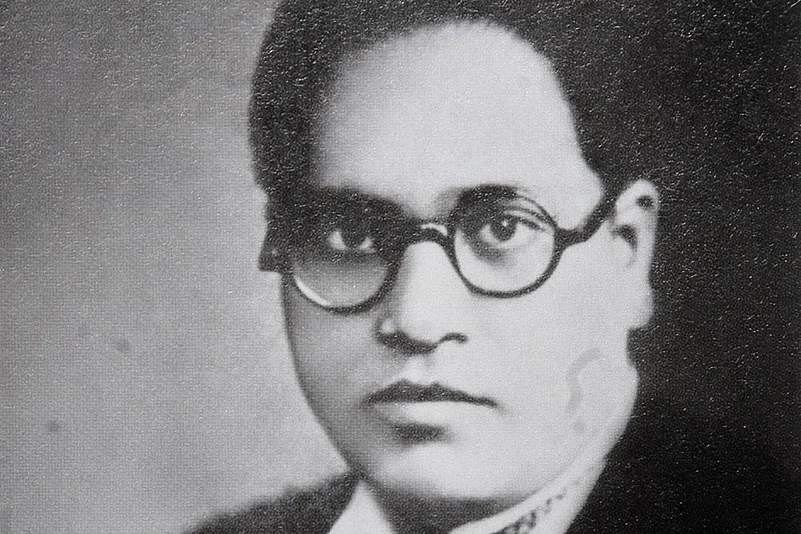

This new collection on Ambedkar brings together international scholars to explore hitherto unexamined aspects of Ambedkar’s praxis and writings. The book is unique in several respects. First is the very thorough comparisons between Ambedkar’s emancipatory struggle for the Dalits and the Black liberation movement(s) in the US. Five chapters address the issue, reflecting on caste and colour, discussing Ambedkar within the contexts of W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King, as well as the anti-apartheid movement.

Second, continuing this effort to see Ambedkar within a global relevance is the pioneering contribution of co-editor Suraj Yengde, who reconstructs and analyses Ambedkar’s foreign policy, tracing the Dalit movement vis-a-vis international and trans-national activism.

Third is just the high standard of scholarship. The contributions by Partha Chatterjee (on Ambedkar’s evolving theory of minority rights) and Rohit De (on Ambedkar’s legal career) are unexpectedly rewarding. There are also excellent chapters by Jean Dreze (on whether contemporary Indian democracy lives up to Ambedkar’s conception), Nicolas Jaoul (on Ambedkar’s conversion), Anupama Rao (on Ambedkar’s figuration of Dalit) and, expectedly, from Sukhadeo Thorat and Anand Teltumbde.

But there is a problem lying hidden in my praise. For the editors did not aim this book to be ‘a major contribution’; rather, they aimed to challenge and subvert the ever-growing field of Ambedkar studies. This brings us to the volume’s most UNIque characteristic: it was conceived within the penumbra of a conspiracy theory.

This is articulated in the editors’ introduction, Reclaiming the Radical in Ambedkar’s Praxis. They assert that the increase in interest in Ambedkar is in inverse proportion to how radical he is depicted as being. As Ambedkar is deradicalised more, his decaffeinated ideology and persona are promoted more and more: “The ruling classes realised the strategic necessity of appropriating Ambedkar to achieve many of the emergent goals—containing the immediate risk of Dalits raising material demands, deradicalising Ambedkar for the longer term, co-opting Dalit leaders, promoting identitarian politics among them and severally preventing the possibility of the Dalit movement drifting towards radicalism.”

Although Yengde and Teltumbde refer to this strategising as “machinations of the ruling classes”, it is presented as a conspiracy theory: “After 1990…government began promoting Ambedkar’s image by encouraging universities to begin studies on Ambedkar…. These activities established the Ambedkar icon...but lost the real Ambedkar to the Dalit masses.”

According to this narrative, the increase in political-scholarly attention to Ambedkar has been engineered to dupe and pacify Dalits who, for their part, have thrown themselves headlong into the trap by deifying a deradicalised Ambedkar.

What, then, do the editors believe must be done? Two things, both reflected in the book’s title: (1) to recover the ‘real’, or the radical, Ambedkar; and (2) to break out from the deifying, hagiographic model dominating Ambedkar studies. Hence, this book is designed to be doubly different: it aims to retrieve the radical in Ambedkar, and to do so not hagiographically but to present critical reflections.

But here’s the rub: the book fails to deliver on either. Neither do we encounter an Ambedkar decisively more ‘real’ or ‘radical’. Nor do we encounter reflections on Ambedkar that are any more ‘critical’ than may be found in works of this calibre. The editors themselves admit to the latter: “…[A] critical examination of Ambedkar’s praxis has obviously not worked fully….[I]t was perhaps too ambitious to sublimate spontaneously from frigid hagiography to critical reflection.”

They also seem, by the end of their introduction, to have surmised the former: “We hope the readers will appreciate this modest attempt at examining Ambedkar’s praxis…” Modest? It was not a modest attempt but the retrieval of the ‘real’ Ambedkar that was promised.

But this volume rightfully merits praise. For, as someone who does not subscribe to the conspiracy theory, it hardly makes any difference whether the editors managed to find a solution.

These contributions may not have presented an Ambedkar more ‘real’, but they do manage to interface Ambedkar into hitherto unexplored terrain, and to do so in exemplary ways. The volume is indispensable for anyone working seriously in Ambedkar studies. At least in this respect, if not quite in the way that the editors had hoped, The Radical in Ambedkar is not just another book on the pile.

(Rathore is author of A Philosophy of Autobiography: Body & Text)