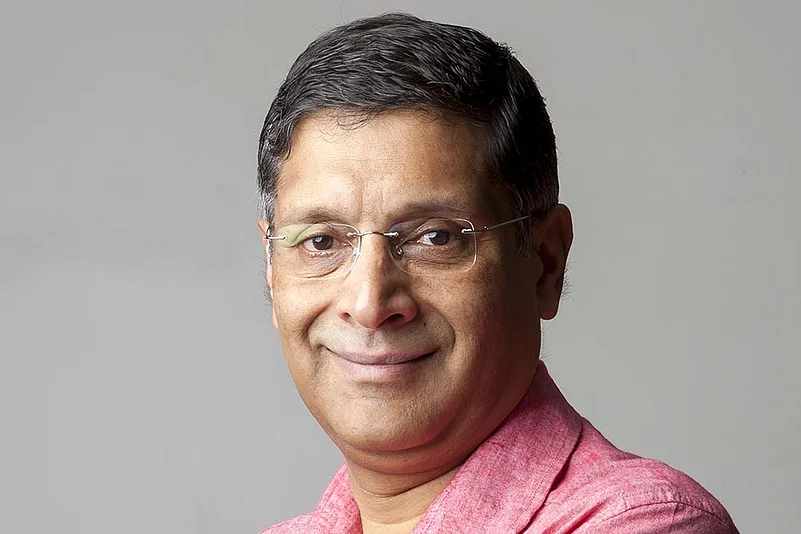

Until recently, Arvind Subramanian was India’s chief economic adviser (CEA). He left his imprint not just on policy, but also on the ‘Economic Survey’. The introduction begins: “I was in Machu Picchu, the site of the spectacular, isolated ruins of the Incan civilisation in Peru, when I first received an email in July 2014 asking if I’d be interested in the job of CEA to the government of India.” Nothing happened for a while. “The delay…arose partly because the nativist sections of the ruling party were opposing me, claiming I had indulged in anti-national activities…. I was appointed CEA in October 2014, although the charge of being mentally un-Indian would come up occasionally during my tenure….” Arvind, as we know, is fond of literature. That introduction quotes T.S. Eliot from Burnt Norton and ends with the line “Into the rose-garden”. The next lines are, “My words echo/Thus, in your mind./ But to what purpose/Disturbing the dust on a bowl of rose-leaves/ I do not know”. Arvind is a friend. Hence, Arvind, why did you write this book? I do not know.

There is a rationale of sorts in the introduction. “One of the responsibilities of having been a privileged witness to history is the need to record for fut-ure historians events and debates, act-ions and reforms of these years…. I can also leave behind a record of my own contributions and failures. Accordingly, this book brings together my writings and reflections during (and since) my four years as the CEA…. Readers should be forewarned that the focus is squarely on policy debates. This is no kiss-and-tell memoir, no gossip-laden account of intrigue, backbiting, favour-trading and double-dealing, no tale of grand heroism and base betrayal.”

The book has eight broad chapters/heads—igniting ideas, money and cash (RBI, twin balance sheet, demonetisation), GST, climate change, agriculture, state versus the individual (JAM, DBT, UBI). Irrespective of their titles, the last two heads are motley mixes. These are heads rather than ‘chapters’, because each head has four or five essays, linked to the theme. Not everything in this volume is new. Some have been published in the past, while Arvind was CEA, or delivered as lectures. But there are some new chapters, such as on demonetisation or RBI’s capital. And there is the introduction.

“In my old office room in North Block, squeezed between portraits of Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, there is a board listing the names of my predecessors…. I saw myself as the custodian of a sacred tradition. I felt responsible for upholding it honorably….” In that list, there are two gentlemen who have been CEA longest—Bimal Jalan and Shankar Acharya. Both have written books thereafter, but never about their track records as CEA. There was no urge to preserve a record for posterity, though they too were privileged witnesses to other phases of history. This is a thin line that transcends the official secrets act. By virtue of being in a certain position within government, one is privy to information. Regardless of what the law says, that information should not be disclosed. This isn’t an absolute moral position and each to his own. In this climate of memoirs, a few of the kiss-and-tell type, there are several non-CEAs who have deviated from the principle.

From the Introduction again, “Perhaps the high point of democratic decision making occurred when Dr Issac (politically opposed to the government on a number of policies, including demonetisation) politely asked to walk out of the meeting because he could not go along with the emerging consensus on taxation of gambling. Jaitley went out of his way to cajole him back and accommodate his views, all the while ensuring that the delicate consensus amongst the other twenty-eight ministers was not ruptured.” I know many former CEAs who wouldn’t have written this, or anything similar. This wasn’t an anecdote that was theirs to share. Despite being a very readable author, had Arvind stuck to pieces published while he was CEA, the volume would have been somewhat dry, even academic. With the tweaking and additions, it has become much more interesting. But, in the process, I have misgivings that Arvind may not have done the office of CEA, and his successors, a good turn. No CEA can ever be faceless and anonymous. But every CEA is part of a broader government machinery and team. (I do not mean the Team CEA that entered and exited with him.) People will look askance at future CEAs, wondering whether discussions are destined for eventual publication. I don’t think that is a desirable outcome.