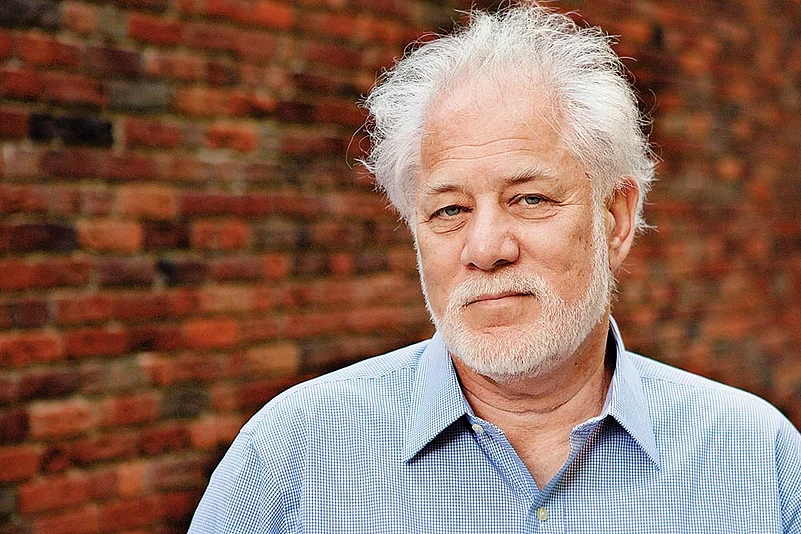

You do not approach a new Michael Ondaatje novel lightly. You tread with care, mindful of his extraordinary achievements, his poetic substance, his slow-winded, softly insidious prose that insinuates itself as it unfolds layers of time, of memory, of recollection and re-comprehension.

It is now more than six years since his last novel. He admits he writes the old-fashioned way, with pen and ink, and revises obsessively. He has published about a dozen collections of poetry, outnumbering his seven novels. Each of his novels is a considered work of fiction, derived from fractured remembrance, explorations and poetic divinations, interwoven and carefully matured in the oaken cask of his consciousness.

His latest novel Warlight is thus to be treated with respect and savoured with thoughtful consideration. As Ondaatje has said elsewhere, “The first sentence of every novel should be: ‘Trust me, this will take time but there is order here, very faint, very human.’ Meander if you want to get to town.”

The first sentence of this novel is a wonderful illustration of this dictum: “In 1945 our parents went away and left us in the care of two men who may have been criminals.” The protagonist, Nathaniel, is a 14-year-old boy and the novel is his first person account of his adolescent years. Not very long afterwards, discoveries take place that call into question the reasons that have been given to the children for their parents’ departure. The multiple mysteries surrounding these and subsequent events are illuminated only gradually towards the end of the narrative, with some surprising twists that would be worthy of any thriller, except that the answers are alluded to so gently that they steal upon the reader softly.

In the meantime, amidst the bombed out streets and houses of the city, there is growing up to do, a first love to be found, sexual discoveries to be made, along with a gradually dawning realisation of the complex lives and motivations of the enigmatic cast of characters that surround the two children. Their personalities and exploits are vividly portrayed, in the fluid environment of a wounded city slowly recovering itself. There are the arcane worlds of greyhound racing and the myriad waterways and canals in and around London to be discovered in the company of one of the mysterious guardians in whose hands the lives of the children have been entrusted. There are delights and disappointments to be experienced and growing up to be done.

In several not insignificant ways, Warlight is a return to the temporal and emotional territory of his magnum opus, The English Patient (1992). Not in terms of geography, but in terms of context and pre-occupations. We are back to the era of the Second World War and its chaotic aftermath. There are two love stories at the heart of it, but it’s almost too late before the reader is allowed to discover the second, perhaps more important one, that has propelled the plot. Time is broken up and layered throughout the narrative, as are the lives and identities of the characters, to achieve an almost thriller-like quality of mystery and ominous significance.

There can be no doubt that some elements are drawn from Ondaatje’s personal recollection. Born in Sri Lanka, his parents separated when he was an infant and he moved with his mother to London as an 11-year-old in 1954. He paints life in post-war London as seen through the eyes of a boy with the clarity of first-hand experience. As he has said in another context, “The past is still, for us, a place that is not safely settled.”

In the latter part of the book, Nathaniel has grown into a young man who sets out on an almost obsessive quest to unravel the riddles of his life since the abandonment. The novel moves “forward in plot, but backwards in time” in a kind of archaeological way, as he tries to retrace the linkages with his parents, particularly his mother, and with the strange cast of characters that surrounded them. In the process, he uncovers the pernicious influence of their wartime preoccupations, as well as another love story that has had a profound impact on their lives. At the very end, revelations that would, coming from a less expert pen, be startling are gently floated onto the surface of the narrative with a quiet precision that is masterly.

In a radio interview a few years ago, Ondaatje said, “I wanted to take what I loved about poetry into fiction.” Warlight is a marvellously compelling and compulsively readable illustration of this fine endeavour.