I got to know Atal Behari Vajpayee because of the kindness of the lady he spent his life with and whose daughter he considers his foster child—Mrs Kaul. I’m not sure why, but she took a shine to me and whenever I wanted an interview, she would ensure that Atal-ji said yes. The funny thing is, it always seemed to happen the same way. I would ring Raisina Road, where Atal-ji lived in the early ’90s, and leave repeated messages asking to speak to him. I have no idea what would happen but he would rarely, if ever, ring back. Then, after my fifth or sixth attempt, Mrs Kaul would come on the line. The first time this happened I was rather embarrassed. I thought she had taken the phone to admonish me for my persistence. It certainly was beginning to feel like pestering. So I began by stammering my apologies.

‘Oho, oho,’ she interrupted and shut me up. ‘You have every right to call, beta, and I know what you want. Let me speak to him. Give me a day or so. Ho jaana chahiye.’ I have to confess that I was sceptical. I thought she was fobbing me off. How wrong I was! When I called back the next morning it was to hear her say, with a chuckle in her voice, that the interview had been fixed. She told me to come that evening and added that Atal-ji had agreed.

I have no doubt that I owe Mrs Kaul a huge debt of gratitude. Without her repeated interventions, the many interviews I did with Atal-ji would never have happened. They included the only one he did after the Babri Masjid demolition as well as another exclusive, six months later, when four BJP state governments in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh that had been dismissed by the prime minister after the masjid demolition, failed to get re-elected.

The BJP slogan at the time was ‘Aaj panch pradesh, kal sara desh’ (Five states today, the entire country tomorrow). I began my interview by mischievously repeating this to him. Of the five states, the BJP had lost four and so the prospect of winning the nation had receded very badly.

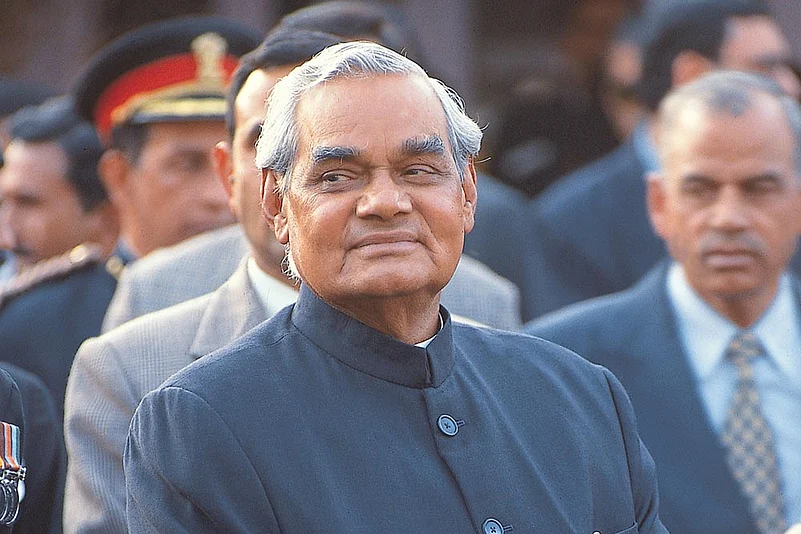

Atal-ji laughed. His face broke into a huge smile and his eyes twinkled. I wasn’t sure if it was mischief or glee. He had a very winning appearance when he was smiling. One’s heart automatically warmed to him.

‘Aaj panch pradesh, kal sara desh,’ he repeated and laughed again. He didn’t need to say more. It was clear he was poking fun at his party’s braggadocio.

While conducting these interviews, my task was to draw him out. If I ever felt the need to challenge him, I would do so gently because I didn’t want to make him defensive and put him off. By and large I succeeded in my goal because most people thought the interviews were eye-opening and, more significantly, they made headlines the next day.

I think I’m right in saying that in the early ’90s Atal-ji felt comfortable with me and I had his trust. The first confirmation of this was just after Rajiv Gandhi’s death in 1991. Eyewitness had planned a special obituary for Rajiv. Our idea was to invite a multitude of people who knew him and ask them to share their most important memory. The aim was to capture something of Rajiv’s personality and the impact he had had on people. When I approached Atal-ji, his initial response was to ask me to meet him before he made up his mind.

What followed was an extraordinary conversation that led to a unique and touching moment in our obituary.

‘I’m happy to speak about Rajiv,’ Atal-ji began. ‘But I don’t want to speak as a leader of the opposition because that would not permit me to say what I really want to. I want to speak as a human being who got to know a side of Rajiv that perhaps no one else in public life has seen. If that is okay with you, I’m happy to be part of the obituary you are planning.’

I wasn’t sure what he had in mind. It sounded intriguing but I needed to know more. So I asked him to tell me what he wanted to say. Apparently, during the early part of his prime ministership, Rajiv Gandhi had learnt that Atal-ji had a kidney problem and needed treatment. So he summoned him to the Prime Minister’s Office in Parliament and said that he intended to make Atal-ji a member of the Indian delegation to the United Nations. He hoped that Atal-ji would accept, go to New York and get treated. And that’s what Atal-ji did. As he told me, this possibly saved his life and now, after Rajiv’s sudden and tragic death, he wanted to make the story public as a way of saying thank you.

Now, this is not the way politicians from opposite sides of the fence usually speak of each other. If ever they do, it’s only in private. Atal-ji’s determination to do so publicly was not just unusual, it was truly unique. More importantly, this was heartfelt gratitude. The story touched a chord within me and I knew it would have the same effect on the audience. It was likely to be the most important bit—the high point, if that’s not an inappropriate term—of the obituary. I readily accepted. We recorded the next day and Atal-ji spoke exactly as he said he would. However, the impact he made was far greater than the actual content of what he had to say. His slow, measured delivery and the obvious emotion that lay behind it made an unforgettable impression on everyone.

When I thanked him for this magical moment, he instead thanked me for giving him the opportunity to say something that he had long wanted to express but didn’t know how to. He said that a weight had been lifted off his mind.

The second occasion when I sensed a special relationship with Atal-ji was during his prime ministership. I had been invited to a banquet at Rashtrapati Bhavan for the president of Guyana. I was standing at one end of Ashoka Hall along with all the other guests when Prime Minister Vajpayee who, because of his weak knees, always used the lift, entered the room from the other side. As he walked across the floor, a hush descended on the gathering. Everyone was looking at him as he slowly but steadily crossed the enormous room.

Suddenly, halfway across, he gestured with his hand as if he was summoning someone out of the forty or fifty people at the other side. Since no one knew whom he was signalling, several people took a couple of steps forward. This made Atal-ji laugh and everyone who had moved forward stepped back and returned to where they were. However, Atal-ji continued to summon. It was then that I suddenly felt he was calling me. So I moved forward again and he confirmed that I was right by pointing straight at me. With everyone watching, I walked across the carpet to talk to the PM. Just a day or so earlier I had written a column critical of him and I wondered if he had read it.

‘Aap ka lekh maine padha tha (I read what you had written),’ Atal-ji began. But he was laughing. Perhaps he was teasing. Still it made me feel awkward, if not guilty.

‘Atal-ji,’ I blurted out. ‘My mother read it too and told me I’m an idiot.’

‘Ma hamesha galat nahi hoti (Mothers aren’t always wrong),’ he said and roared with laughter.

Then he put his hand on my shoulder and chatted for another minute or two. I knew at once that he wasn’t in the least bit upset. It took me just a little longer to realise that the PM was also sending a deft message to everyone else. Many of them would have read what I had written and were perhaps wondering how he would react. This display of friendliness was also meant to set their minds at rest. It was smart proof that the PM didn’t mind criticism. Like a good democrat—and a wise politician—he was visibly rising above it. For me, this was abiding proof that Atal-ji is not just a good man but also an astute politician. With the smallest of gestures, he could send the biggest of messages. And he had the ability of doing so in the most natural of ways. This was just one example. In his political career of several decades there must have been thousands more.