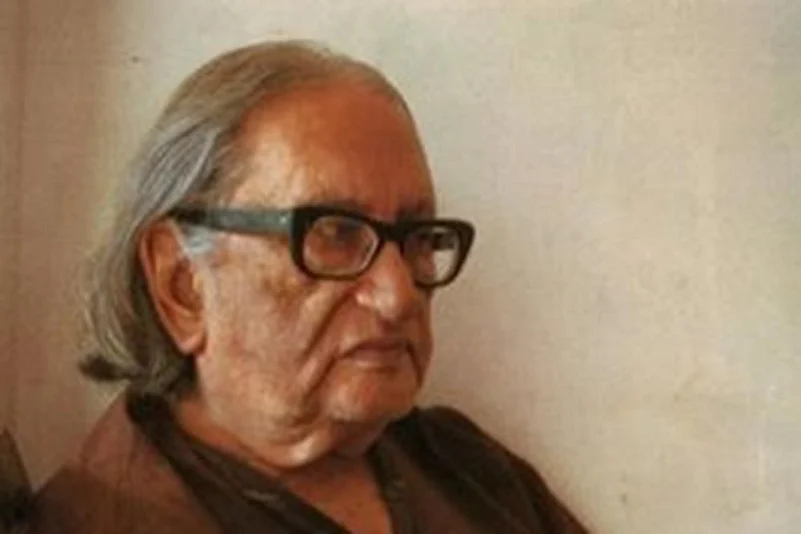

In Colombo’s multi-ethnic Borella suburb, George Keyt ventures on a year’s art expedition across the new walls of a Buddha temple whose environs stimulated his aesthetics from childhood as a Sri Lankan of British descent. The 1939-40 work gifts Gotami Vihara with not just sensual visuals of the Buddha’s life; the many-hued etchings also usher in the first brush of modernity for Sri Lankan art.

Keyt’s frescoes “humanised and secularised” the life story of the sage who lived five centuries before Christ, expanding the “nationalist and traditionalist” ethos of this religious project “towards the global modern”. As Yashodhara Dalmia notes, Keyt’s pioneering depiction of Mara and the demon’s armies bears stylistic similarities with Pablo Picasso’s.

For all his adoration for the Spaniard, this was one observation Keyt (1901-93) abhorred as he evolved. The book later notes the artist ruing that the West wasn’t well exposed to Kalighat and India’s miniature paintings, to which he had an affinity, alongside an admiration for Jamini Roy and Rabindranath Tagore. After all, Keyt’s Yashodhara wasn’t fair-skinned; instead, she wore the complexion of the artist’s second wife, Pillawela Manike, a native of Kandy hills.

The bohemian Keyt’s art ranged from the ancient Sigiriya murals off Dambulla to Picasso’s Cubism, notes Dalmia. His “robust forms and brilliant colours” fused the East and West—only to influence subsequent generations, as did Amrita Sher-Gil—amidst an association with titans like M.F. Husain and F.N. Souza. Keyt’s own “tempestuous life” infused his art, something the book makes amply clear.

Keyt’s forefathers were from Yorkshire; his great-grandfather lived in Hyderabad, where a liaison with a courtesan of the Nizam triggered a professional dislocation that eventually fetched the civil servant a posting in Ceylon. Born to a Burgher mother, George’s father died when he was young; the boy undertook formal schooling only after he was 10—drawing and colouring all through his childhood. This ‘incubation’ enabled him to portray local mythology and folk tales.

Keyt’s early works as a 26-year-old looked “like an ethnographic study”, though a more fluid body language pointed to his “breaking out staticity”. In 1930, Keyt married Gladys Ruth, the sibling of his only sister Peggy’s friend. The “light-eyed, raven-haired” lady mothered two girls, but her strong Catholic beliefs proved a mismatch vis-a-vis Keyt’s unconventional conduct. Ruth deserted her husband on finding him in the arms of their maid. With Manike, the domestic help, Keyt settled in serene Ranawana.

This Manike-accompanied stint—which shifted to Amunugama to Srimalwatta in 1950, by when they built a house with a huge studio—groomed Keyt’s most intense desire: to practise indigenous art methods. Manike was knowledgeable about Kandyan culture, but the marriage was troubled, what with the artist’s flings with other women, many of which Manike was aware of, but chose not to be fussy. Keyt’s Jalaja series (1938-39) reflected the artist’s agitated self, while the calmer Nayika of 1942 borrowed from Indian traditions of Mewar and Basohli.

Keyt had by then visited India with sister Peggy and her Sanskrit scholar husband Harold Peiris. This maiden 1939 trip exposed him to the temples of Tamil Nadu and a Kathakali evening in Kerala, but what the artist painted on his return was about the freedom struggle. The Rejection of Siva (1942) was followed by another anti-imperialist work, Bhima and Jarasandha, a year later. A 1946 India stint took him to Mathura, Kurukshetra and inner Rajasthan. His female figures in Lalita Ragini (1952) were inspired by medieval-era Ragamala paintings.

Parallely, women kept entering his life—to the extent that Manike suffered a nervous breakdown. Kusum Narayan, a much younger lady from Bombay married Keyt when he was in his 60s, as per Islamic rituals. A Christian, the artist aspired to be a Buddhist monk, considered himself a Hindu and converted to become a Muslim, notes Dalmia about Keyt, also quoting passionate letters he exchanged with Bombayite Anglo-Indian Barbara Buchannan, a single woman who was into publishing.

Correspondences with key people are prominently placed, and often pieced together as story threads. Dalmia’s long descriptions about two men—art promoter Martin Russel and cultural theorist Van Geyzel—with whom Keyt corresponded, show her hyper-link approach, which is also evident in her details about Lanka’s epoch-defining ’43 Group of independent artists. Keyt’s sense of beauty was primarily Asian, she emphasises, as she talks about a turbulent life capped with global recognition. Keyt went on to paint amid end-game bouts of ill-health and penury.