To paraphrase India’s one and only Independent Mobile Republic: "I opened this book, surveyed the devastation wrought by Quark Xpress and winced."

Digital editing adds a frightening new weapon to the arsenal of the motivational writing brigade. In Dale Carnegie’s day, motivators stuck to basic 1,000-word vocabularies and simplistic ideas. Now they think nothing of scattering CAPITAL LETTERS, words in bold, portentous sentences in italics and three different fonts across pagefuls of charts and textboxes.

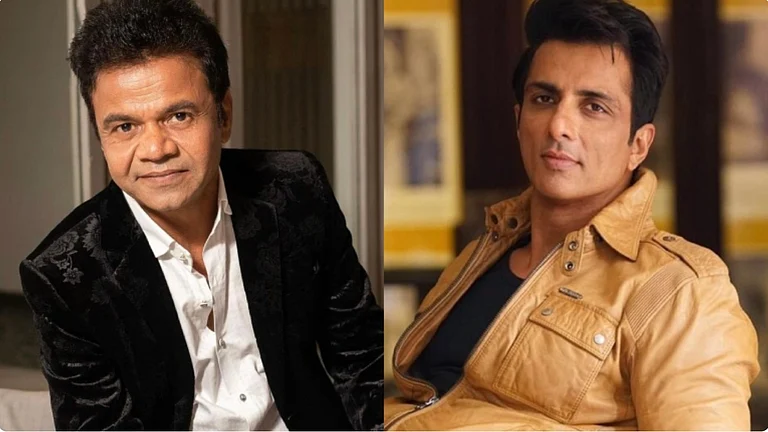

Arindam Chaudhuri hit the jackpot writing in this style, if it may be so termed, in Count Your Chickens Before They Hatch. He and his father Malay have collaborated on The Great Indian Dream (TGID), which showcases their socio-economic philosophy.

It’s an unusual mating of style and content. TGID is a macro-economic pamphlet. The self-help format implies the target reader is the lowest common denominator. But economic policy is made by a small uber-class.

The mismatch between target audience, content and style enhances the book’s entertainment value. Written conventionally, it would have been tedious. Instead, it’s a page-turner, but not perhaps for the reasons the authors intended. Motivational tracts and macro-economics both deal in sweeping generalisations. TGID offers fantastic variations on this theme.

"Globalisation is bad, it creates dysfunctional societies like the us" is old hat at college debates. But did you know globalisation is so bad that American kids cease to love their parents at 14? Materialistic, globalised American kids demand their own cars at 14. Parent refuses car, kid ceases to love parent—QED.

The logic of TGID runs thus: A) India has problems: poor governance, low HDI, rotting grain-mountains and starvation deaths; B) Globalisation (catchily dubbed ‘Dictatorial Capitalism’) has much wrong with it; C) India cannot eradicate A simply by adopting B; and D) If India adopts TGID’s policy prescription (termed ‘Happy Capitalism’) instead, it will become rich and powerful in 25 years.

Nobody can dispute A or B. On C, one could argue that India has little choice about adopting some version of B. It’s on D that opinions could differ.

TGID’s prescription is ludicrous. Happy Capitalism is centralised planning in a new bottle. As the authors note, planning made a mighty nation out of the (late) Soviet Union!

TGID suggests big taxes on petro products, power, vehicles, edible oils and sugar. The new tax revenues will be spent on social security measures; these will kickstart 12.5 per cent GDP growth per annum. That rate will compound over 25 years, making India a mega-economy.

In TGID’s opinion, new imposts of Rs 10 a litre on diesel and on edible oil will "hardly be noticed" and "have a negligible impact on inflation". May one suggest that the authors haven’t done much thinking out of the box? Legalising and taxing porn, dope and gambling would cause less inflation and even less social unrest.

In this brave new land, social security will be guaranteed through minimum wages and doles. Salaries will be capped. CEOs will receive a maximum of 3-5 times the compensation of the lowest-paid employees. (Albania with a 1:2 ratio of flunky:CEO salaries is a cited model of income parity.)

Indian economy will be protected from MNCs. Fiscal deficits will be met by printing more notes. Rural management schools will create Grameen MBAs. Corporate tax rates will be lowered. Governance will be improved by executive presidency, justice speeded up by hiring emergency judges, if necessary straight out of law school.

While India embarks on this 25-year exercise in socio-economic engineering, people will learn to live by the Law of Increasing Marginal Returns so that they don’t hanker after more goods. This concept, somewhat fuzzy even after a diligent re-read, has something to do with people spending more time with friends and family, less money on buying new gizmos.

To drive home their parables, the authors have "invented" cartoon characters: the Empty Warhead in the White House, rich, unhappy Bill Dates and politician Bill Dingdong, who dates his secretary Monica. There is also Pablo Hussain, society painter of horses, who wears only one slipper.

The book also plugs the Delhi Italian restaurant Flavors: proprietor Tarsillo Nataloni has a Happy Capitalistic attitude; he has no desire to increase his income. I haven’t a clue whether this is true of Signor Nataloni. But I endorse the plug: the food at Flavors is to die for, as are the cute Mizo waitresses.