“Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of the radio, believed that sound waves never completely die away, that they persist...masked by the day-to-day noise of the world. Marconi thought that if he could only invent a microphone powerful enough, he would be able to listen to the sound of ancient times. The Sermon on the Mount, the footfalls of Roman soldiers marching down the Appian Way.”

That stray observation by Seth, the young, white, introverted, middle-class narrator of White Tears, has a resonance that reverberates through the plot of this singular novel. Early in the narrative, Seth teams up with a rich, enigmatically charismatic drifter named Carter Wallace, who leads him into his own obsessive world. At their first meeting on the campus of the upstate New York college where they are students, Seth is eavesdropping on distant conversations, using a directional microphone mounted in a homemade parabolic reflector made out of an old satellite dish. Carter suggests they go back to his dorm room to listen to music. The records are vinyl and the equipment is analog. “Gradually I noticed that everything he played was by Black musicians. Many different styles, but always Black music...unfamiliar to me.”

Seth goes on: “Over the next weeks and months, Carter taught me to worship—it’s not too strong a word—what he worshipped. He listened exclusively to Black music because, he said, it was more intense and authentic than anything made by white people. He spoke as if ‘white people’ were the name of an army or gang, some organisation to which he didn’t belong.”

After they finish college, Carter sets up an analog recording studio financed by his trust fund money and Seth joins him. By this time, Carter’s musical obsessions have regressed progressively from vinyl to shellac, from “ska and soca, soul and RnB, seventies Afrobeat and eighties electro”, through “scratchy 45s of doo-wop bands” to 78 rpm “pre-war blues recordings, lone guitarists playing strange abstract figures, scraping the strings with knives and bottlenecks and singing in cracked...voices about trouble and loss”.

Carter is dismissive about later recordings as not real enough, “tainted by the digital sins of modernity”. “Just zeroes and ones.” So it is ironical that these two boys use digital technology to create an authentic sounding blues track out of an accidental recording made by Seth of a black chess player singing to himself in Washington Square. They give it the patina of an old 78-rpm record and Carter releases it on the net on a file-sharing site as a purportedly re-discovered rare, old record by a singer named Charlie Shaw.

This singular act of musical forgery triggers a series of events that set off a long downward spiral through the second half of the novel. The problem is that if this is a rare old 78, there has to be a Side B, but there is none. The specialist collectors who come across the recording on the net are obsessed by this question, in particular an old collector who has the username JumpJim. JumpJim becomes a secondary narrator of the novel, as he tells his own story of accompanying an older collector on a road trip to Mississippi in his youth in search of rare Blues records. The narratives blur into each other, veering from the present to the past and back. The seemingly actual blurs into the seemingly fantastical. Is Charlie Shaw Carter’s fictional creation or was he an actual historical figure? Has Seth’s powerful microphone picked up a Marconi-esque echo from the past? Is it Charlie Shaw’s ghost who comes back to haunt and to seek vengeance, or is it a product of Seth’s troubled mind?

From these strands of plot emerge a compelling narrative of the racial exploitation that found such searing expression in the Blues. It emerges that the wealth of Carter’s family is based on this exploitation, which continues into the 21st century in altered guise.

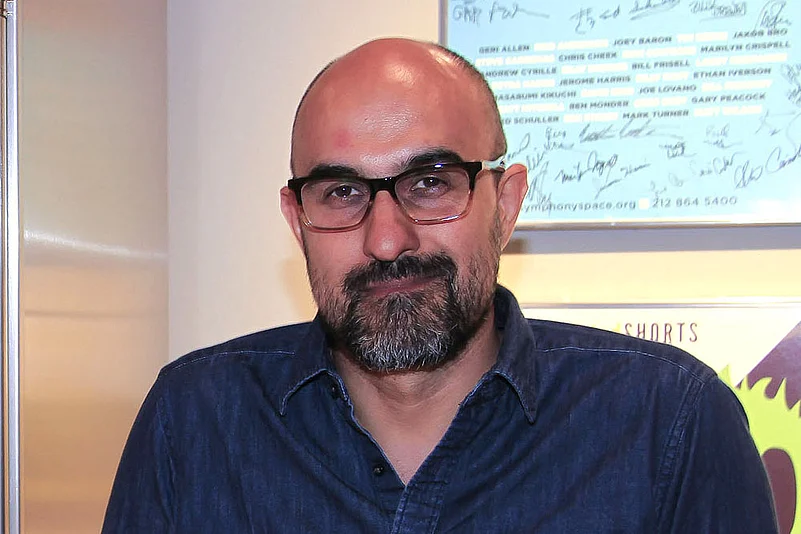

Part road trip, part ghost story, the narrative winds its hallucinatory way towards a gruesome finale reminiscent of a Tarantino film. Racial guilt and obsession are played out to the plaintive and disturbing soundtrack of the Blues. Despite Kunzru’s somewhat self-conscious artifice, manifested in such devices as jumping without warning between at least three different narrative voices separated by time and space and the avoidance of quotation marks in direct speech, White Tears is compelling and disturbing, haunted as much by the spirits of the real-life obscure singers of the early Blues as by the ghost of the fictional Charlie Shaw. It is a fine addition to the oeuvre of a writer who has been hailed as “one of our most important novelists”, as the suitably black-and-white cover reminds us.