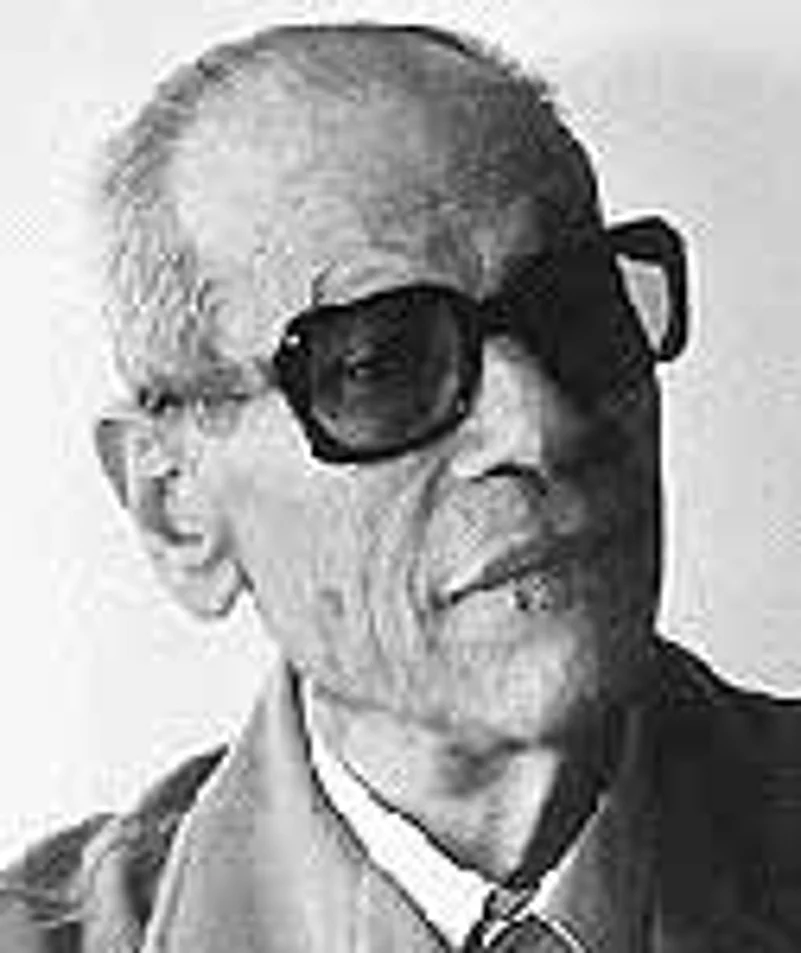

Before he won the Nobel Prize in 1988, Naguib Mahfouz was known outside theArab world to students of Arab or Middle Eastern studies largely as the authorof picturesque stories about lower-middle-class Cairo life. In 1980 I tried tointerest a New York publisher, who was then looking for "Third World"books to publish, in putting out several of the great writer's works in first-rate translations, but after a little reflection the idea was turned down. WhenI inquired why, I was told (with no detectable irony) that Arabic was acontroversial language.

A few years later I had an amiable and, from my point of view, encouragingcorrespondence about him with Jacqueline Onassis, who was trying to decidewhether to take him on; she then became one of the people responsible forbringing Mahfouz to Doubleday, which is where he now resides, albeit still inrather spotty versions that dribble out without much fanfare or notice. Rightsto his English translations are held by the American University in Cairo Press,so poor Mahfouz, who seems to have sold them off without expecting that he wouldsomeday be a world- famous author, has no say in what has obviously been anunliterary, largely commercial enterprise without much artistic or linguisticcoherence.

To Arab readers Mahfouz does in fact have a distinctive voice, which displaysa remarkable mastery of language yet does not call attention to itself. I shalltry to suggest in what follows that he has a decidedly catholic and, in a way,overbearing view of his country, and, like an emperor surveying his realm, hefeels capable of summing up, judging, and shaping its long history and complexposition as one of the world's oldest, most fascinating and coveted prizes forconquerors like Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon, as well as its own natives.

In addition Mahfouz has the intellectual and literary means to convey them ina manner entirely his own--powerful, direct, subtle. Like his characters (whoare always described right away, as soon as they appear), Mahfouz comes straightat you, immerses you in a thick narrative flow, then lets you swim in it, allthe while directing the currents, eddies, and waves of his characters' lives,Egypt's history under prime ministers like Saad Zaghlul and Mustafa El-Nahhas,and dozens of other details of political parties, family histories, and thelike, with extraordinary skill. Realism, yes, but something else as well: avision that aspires to a sort of all-encompassing view not unlike Dante's in itstwinning of earthly actuality with the eternal, but without the Christianity.

Born in 1911, between 1939 and 1944 Mahfouz published three, as yetuntranslated, novels about ancient Egypt while still an employee at the Ministryof Awqaf (Religious Endowments). He also translated James Baikie's book AncientEgypt before undertaking his chronicles of modern Cairo in Khan Al-Khalili,which appeared in 1945. This period culminated in 1956 and 1957 with theappearance of his superb Cairo Trilogy. These novels were in effect a summary ofmodern Egyptian life during the first half of the twentieth century.

The trilogy is a history of the patriarch El- Sayed Ahmed Abdel-Gawwad andhis family over three generations. While providing an enormous amount of socialand political detail, it is also a study of the intimate relationships betweenmen and women, as well as an account of the search for faith of Abdel-Gawwad'syoungest son, Kamal, after an early and foreshortened espousal of Islam.

After a period of silence that coincided with the first five years followingthe 1952 Egyptian revolution, prose works began to pour forth from Mahfouz inunbroken succession--novels, short stories, journalism, memoirs, essays, andscreenplays. Since his first attempts to render the ancient world Mahfouz hasbecome an extraordinarily prolific writer, one intimately tied to the history ofhis time; he was nevertheless bound to have explored ancient Egypt again becauseits history allowed him to find there aspects of his own time, refracted anddistilled to suit rather complex purposes of his own.

This, I think, is true of Dweller in Truth (1985) translated into English in1998 as Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth, which in its unassuming wayis part of Mahfouz's special concern with power, with the conflict betweenorthodox religious and completely personal truth, and with the counterpointbetween strangely compatible yet highly contradictory perspectives that derivefrom an often inscrutable and mysterious figure.

Mahfouz has been characterised since he became a recognised world celebrityas either a social realist in the mode of Balzac, Galsworthy, and Zola or afabulist straight out of the Arabian Nights (as in the view taken by J M Coetzeein his disappointing characterisation of Mahfouz). It is closer to the truth tosee him, as the Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury has suggested, as providing inhis novels a kind of history of the novel form, from historical fiction to theromance, saga, and picaresque tale, followed by work in realist, modernist,naturalist, symbolist, and absurdist modes.

Moreover, despite his transparent manner, Mahfouz is dauntingly sophisticatednot only as an Arabic stylist but as an assiduous student of social process andepistemology--that is, the way people know their experiences--without equal inhis part of the world, and probably elsewhere for that matter. The realisticnovels on which his fame rests, far from being only a dutiful sociologicalmirror of modern Egypt, are also audacious attempts to reveal the highlyconcrete way power is actually deployed. That power can derive from the divine,as in his parable Awlad Haritna (Children of Gebelaawi) of 1959 inwhich the great estate owner Gebelaawi is a godlike figure who has banished hischildren from the Garden of Eden or from the throne, the family, and patriarchyitself, or from civil associations such as political parties, universities,government bureaucracy, and so on. This isn't to say that Mahfouz's novels areguided by or organised around abstract principles: they are not, otherwise hiswork would have been far less powerful and interesting to his uncounted Arabreaders, and also to his by now extensive international audience.

Mahfouz's aim is, I think, to embody ideas so completely in his charactersand their actions that nothing theoretical is left exposed. But what has alwaysfascinated him is in fact the way the Absolute--which for a Muslim is of courseGod as the ultimate power--necessarily becomes material and irrecoverablesimultaneously, as when Gebelaawi's decree of banishment against his childrenthrows them into exile even as he retreats, out of reach forever, to hisfortress--his house, which they can always see from their territory. What isfelt and what is lived are made manifest and concrete but they cannot readily begrasped while being painstakingly and minutely disclosed in Mahfouz's remarkableprose.

Malhamat Al-Harafish (1977), Epic of the Harafish, extends anddeepens this theme from Children of Gebelaawi. His subtle use of languageenables him to translate that Absolute into history, character, event, temporalsequence, and place while, at the same time, because it is the first principleof things, it mysteriously maintains its stubborn, original, if also tormentingaloofness. In Akhenaten the sun god changes the young, prematurelymonotheistic king forever but never reveals himself, just as Akhenaten himselfis seen only at a remove, described in the numerous narratives of his enemies,his friends, and his wife, who tell his story but cannot resolve his mystery.

Nonetheless Mahfouz also has a ferociously antimystical side, but it is rivenwith recollections and even perceptions of an elusive great power that seemsvery troubling to him. Consider, for instance, that Akhenaten's story requiresno fewer than fourteen narrators and yet fails to settle the conflictinginterpretations of his reign. Every one of Mahfouz's works that I know has thiscentral but distant personification of power in it, most memorably thedominating senior figure of El-Sayed Ahmed Abdel-Gawwad in the Cairo Trilogy,whose authoritative presence hovers over the action throughout the triology.

In the trilogy his slowly receding eminence is not simply offstage, but isalso being transmuted and devalued through such mundane agencies asAbdel-Gawwad's marriage, his licentious behavior, his children, and changingpolitical involvements. Worldly matters seem to puzzle Mahfouz, and perhaps evencompel as well as fascinate him at the same time, particularly in his account ofthe way the fading legacy of El-Sayed Abdel-Gawwad, whose family is Mahfouz'sactual subject, in the end still manages to hold together the three generations,through the 1919 Revolution, the liberal era of Saad Zaglul, the Britishoccupation, and the reign of Fouad during the interwar period.

The result is that when you get to the end of one of Mahfouz's novels youparadoxically experience both regret at what has happened to his characters intheir long downward progress and a barely articulated hope that by going back tothe beginning of the story you might be able to recover the sheer force of thesepeople. There is a hint of how gripping this process is in a fragment called"A message" contained in the novelist's Echoes from anAutobiography (1994): "The cruelty of memory manifests itself inremembering what is dispelled in forgetfulness." Mahfouz is an unredemptivebut highly judgemental and precise recorder of the passage of time.

Thus Mahfouz is anything but a humble storyteller who haunts Cairo's cafésand essentially works away quietly in his obscure corner. The stubbornness andpride with which he has held to the rigour of his work for a half-century, withits refusal to concede to ordinary weakness, is at the very core of what he doesas a writer. What mostly enables him to hold his astonishingly sustained view ofthe way eternity and time are so closely intertwined is his country, Egyptitself. As a geographical place and as history, Egypt for Mahfouz has nocounterpart in any other part of the world. Old beyond history, geographicallydistinct because of the Nile and its fertile valley, Mahfouz's Egypt is animmense accumulation of history, stretching back in time for thousands of years,and despite the astounding variety of its rulers, regimes, religions, and races,nevertheless retaining its own coherent identity. Moreover, Egypt has held aunique position among nations. The object of attention by conquerors,adventurers, painters, writers, scientists, and tourists, the country is like noother for the position it has held in human history, and the quasi-timelessvision it has afforded.

To have taken history not only seriously but also literally is the centralachievement of Mahfouz's work and, as with Tolstoy or Solzhenitsyn, one gets themeasure of his literary personality by the sheer audacity and even theoverreaching arrogance of his scope. To articulate large swathes of Egypt'shistory on behalf of that history, and to feel himself capable of presenting itscitizens for scrutiny as its representatives: this sort of ambition is rarelyseen in contemporary writers.

Mahfouz's Egypt is a charged one, strikingly vivid for the accuracy andhumour with which he portrays it, in a mode that is neither completely takenwith great heroes nor able to do without some dream of total harmony of the kindAkhenaten so desperately strives to keep but cannot sustain. Without a powerfulcontrolling centre, Egypt can easily dissolve into anarchy or an absurd,gratuitous tyranny based either on religious dogma or on a personaldictatorship.

Mahfouz is now ninety years old, nearly blind, and, after he was physicallyassaulted by religious fanatics in 1994, is said to be a recluse. What is bothremarkable and poignant about him is how, given the largeness of his vision andhis work, he still seems to guard his nineteenth- century liberal belief in adecent, humane society for Egypt even though the evidence he keeps dredging upand writing about in contemporary life and in history continues to refute thatbelief. The irony is that, more than anyone else, he has dramatised in his workthe almost cosmic antagonism that he sees Egypt as embodying between majesticabsolutes on the one hand and, on the other, the gnawing at and wearing down ofthese absolutes by people, history, society. These opposites he never reallyreconciles. Yet as a citizen Mahfouz sees civility and the continuity of atransnational, abiding, Egyptian personality in his work as perhaps survivingthe debilitating processes of conflict and historical degeneration which he,more than anyone else I have read, has so powerfully depicted.

© Copyright Al-AhramWeekly. All rights reserved