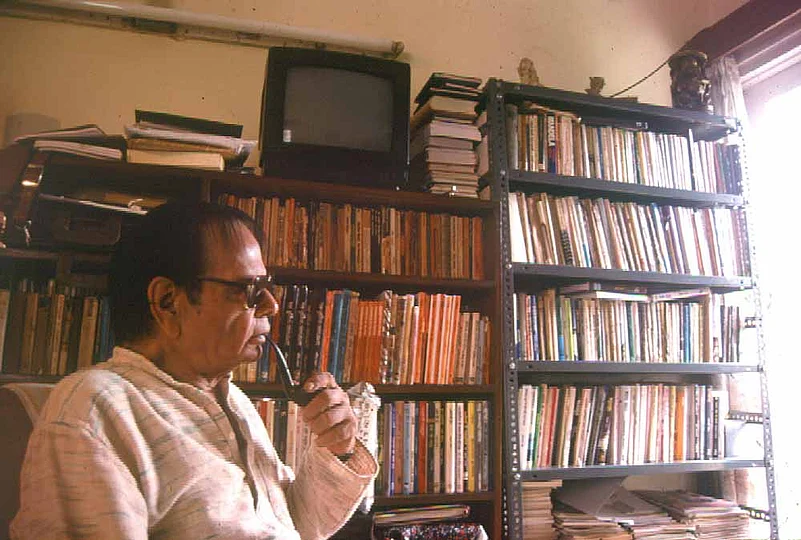

Regular readers of his Hindi literary magazine, Hans, which opens every month with a hard-hitting signed editorial column, are familiar with the personality trait that defines Rajendra Yadav the man and the writer. Pugnacity. That's his signature. In a career spanning over half a century—he wrote his first story, Pratihinsa, in 1947—Yadav has never flinched from speaking his mind, from taking up cudgels on behalf of causes he holds dear. So neither in Mandi House nor in Shastri Bhavan is this disconcertingly combative member of the Prasar Bharati board a particularly popular personality. Yadav, who turned 70 last week, spares nobody. Not the software producers and anchors who are all too willing to bend over backwards; not the bureaucrats who've made such a pathetic mess of Doordarshan; not even the information and broadcasting minister who never tires of airing his personal views on why the government shouldn't let go of the official electronic media. "In the absence of any real powers, this is all I can do—make a lot of noise," he says.

Yadavspeak

Rajendra Yadav on Pramod Mahajan and the Prasar Bharati mess

"Loudmouth politicians are forgotten by history. In the '80s, K.K. Tewary used to shoot his mouth off on everything. Who remembers him today?"

"The Prasar Bharati is hamstrung. We've no financial and punitive powers. No control on service rules either. So we can, at best, play the role of a declawed, defanged watchdog."

"When a programme proposal is submitted to DD, implementation can happen only when the board passes a resolution. In the case of the live election telecast, the minister made a unilateral decision. We were not taken into confidence."

"The Prasar Bharati structure is still incomplete. The government seems to be deliberately delaying the process."

"What the minister thinks about DD autonomy doesn't matter. Only Parliament has the power to disband Prasar Bharati."

Yadav's voice has, for once, been heard. Following an Election Commission directive to the I&B ministry to let DD's newsroom function independently, the outspoken man of Hindi letters has assumed the responsibility of receiving and acting upon public grievances about the national broadcaster's newscasts. Though a large part of his working day is devoted to Hans—he's the editor, printer, publisher and production hand all rolled into one—Yadav gives all the attention he possibly can to the one-man complaints cell that now functions from a room in central Delhi's Akashvani Bhavan. "I receive 60 to 70 complaints every day. It's my job to bring them to the notice of the Prasar Bharati board," he reveals. Knowing him, one can be sure that no complaint will be lodged in vain.

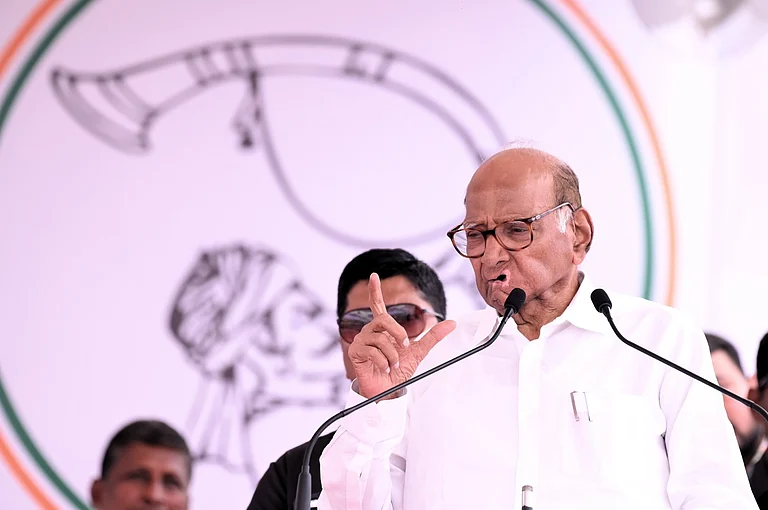

DD's news and current affairs shows are still laced with far too much bias, Yadav feels. Last week's episode of Nishan (on DD News), which featured an interview with I&B minister Pramod Mahajan, appeared to be an image-building exercise for the BJP leader rather than an objective interview. "I'll raise this at the next meeting of the Prasar Bharati board," he says. He has no illusions about the extent of Prasar Bharati's authority over the airwaves and on the ground—"We have no financial and punitive powers," he laments—but he is determined to make the most of a rather bad bargain. "Given the present Prasar Bharati structure, administrative control is still firmly in the hands of the bureaucrats," he asserts. "But as watchdogs we do have the power to bark when we sense something is going amiss." Yadav feels that the Prasar Bharati Corporation has the potential of being as powerful as the Election Commission "if only the government were serious about giving it a fair chance".

Even if he seems to be ploughing a lonely furrow in his fight to save Prasar Bharati's autonomy, he is not unduly perturbed. It's been his lot all along, as much in life as in literature. Yadav who, along with Kamleshwar and Mohan Rakesh, spearheaded the Nai Kahani movement in Hindi literature in the '50s and '60s, has guarded his creative and intellectual freedom all his life, spurning jobs and awards at will. In 1951, the year his first novel Sara Akash came out, he topped Agra University's MA (Hindi) examinations, but he refrained from joining the employment queue. "A writer," he argues, "should never work for anybody. It can only undermine his freedom." His spartan lifestyle—it's in ample evidence both in his office in old Delhi's congested Ansari Road and in his apartment in east Delhi's Mayur Vihar—has helped. "My personal needs have always been limited," he says. His only daughter Rachna, an interior designer, is married to leading photographer Dinesh Khanna. His wife, Hindi novelist Mannu Bhandari, has retired as Miranda House teacher and lives in her own flat in Hauz Khas. "They need absolutely nothing from me in material terms," says Yadav.

So whatever money that comes to him these days is ploughed into Hans, which is now more than a mere magazine. It has emerged as a platform for new talent in Hindi fiction and for lively debates on issues of contemporary relevance. Because of his suspicion that most literary awards are a result of manipulation, Yadav has also consistently declined to accept any. Except for one from the Bihar government. "The award carried a cash prize of Rs 1 lakh and I needed the money for Hans," Yadav confesses with trademark candour. "But ideally, awards should be done away with. Instead, the government should buy copies of a writer's book and distribute them free. For the writer, the royalty would come in handy," he suggests.

The literary magazine he edits was launched by Munshi Premchand in the early '30s. It closed down after the writer's death. Yadav, with a long, fruitful creative writing career behind him, revived it in August 1986 and since then, Hans has come out every month without a break "thanks to the help and support of friends".

Yadav's career graph is replete with unpredictable twists and turns. His early work—which laid bare the grim reality and constant struggle of lower middle-class existence in post-Independence India—was a revolt against the romanticism of the stories of yore. "We (the Nai Kahani exponents) were from the middle-class ourselves and we wrote about the middle-class, and for the middle class. That is perhaps why we clicked," he says. Then came a point when Yadav felt "a sense of futility" in the effort to reflect middle-class angst through fiction. "So I turned to fantasies in an attempt to capture the 'essence' of reality," he reminisces. This productive phase saw Yadav write a large number of Kafkaesque tales.

After producing seven novels, twelve anthologies of short stories and highly acclaimed translations of Anton Chekhov, Albert Camus and John Steinbeck, Yadav turned his back on creative writing in the early '80s for he felt he had exhausted all its possibilities as a means of articulating his socio-political concerns. Hans bailed him out of the trough. Today, he uses the magazine's monthly editorial column to articulate his strong views on politics, society and literature. When Yadav was nominated to the Prasar Bharati board by the I.K. Gujral government, many had felt that he was going back on his vow not to hold any official position. "I accepted it only because I felt it was a good opportunity for me to help free Doordarshan from the clutches of the government."

The Prasar Bharati board may not have made much headway in the face of stiff odds, but Yadav isn't one to give up trying.