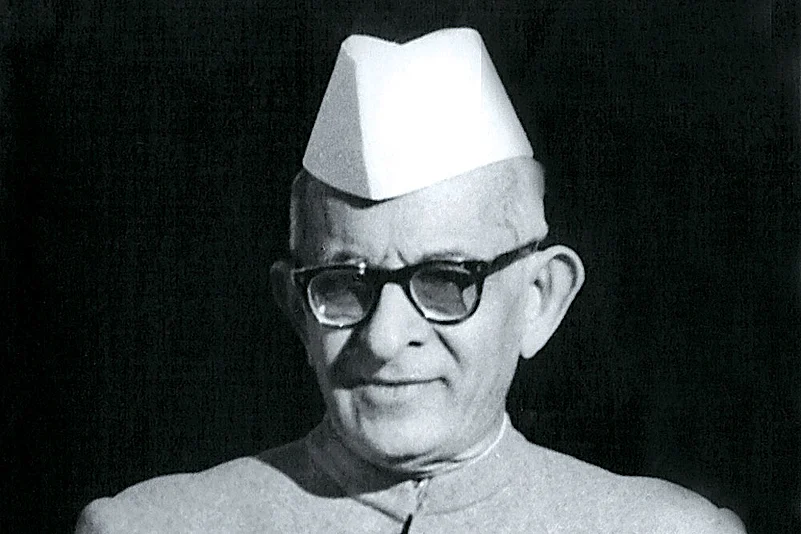

KM. Munshi is the most famous Gujarati writer since Narsinh Mehta, the poet who composed Gandhi’s favourite hymn Vaishnav Jan. But unlike Mehta, Munshi was bilingual. He studied and expressed himself (including in the Constituent Assembly, of which he was part) in English.

Munshi, who died in 1971, was a lawyer and politician. He was a Congressman, who left the party, the translators tell us, because he opposed Gandhi’s call for all Congressmen to dissociate from akhadas and other violent physical activity. He was a modernist and sided with Nehru and against Gandhi and Tagore in the English versus mother tongue debate on the medium of education in government schools.

Despite his various activities, Munshi is most famous for his novels, which have educated and prejudiced generations. It is the very rare Gujarati individual who has not encountered Munshi’s stories. Debates (perhaps we should call them shouting matches) about Muslims in Gujarat will begin with Somnath, which was sacked a thousand years ago. Much of this owes to the novels of Munshi.

The Gujarati refrain is e loko e sharu karyun (they started it) and the ideas of collective, monolithic identity and Gujarati pride on real or imagined pre-Muslim history owes much to Munshi. He invented the phrase ‘Gujarati Asmita’, writing an essay on it. However, it is his fiction series on the kings of Anhilwad Patan and on Somnath (he headed the temple trust and its structure was rebuilt under him) that is his most important legacy. This novel is the first in the series.

The story is set in the 12th century, in the years of Hindu rule before Gujarat was conquered by Allauddin Khilji’s generals around 1297. The trilogy’s real hero is the minister Munjal Mehta, a Bania who, as was the tradition among the Rajputs of Gujarat, ran the kingdom because they were the only ones literate.

The novel begins with Mehta (the word itself means accountant) advising a young king and his mother after the death of the ruler. Some of the characters are historical, many are fictional. The romance between Mehta and the dowager Minal is also most likely a fiction. A Bania man-Rajput woman romance hasn’t upset Gujarat’s Rajputs as much as such things regularly seem to miff Rajputs elsewhere in India.

The Glory of Patan is a terrific read—I mean the opening bits. Specifically, the first 31 pages: the introduction and historical background written by the translators, Rita Kothari and Abhijit Kothari. They profile Munshi and locate his work and analyse it very well.

The novel itself is unreadable. It is like a Hindi serial: loud, obvious and overly emotional. Long dead women return, teen lovers sulk, despairing mothers break down. Such things pepper the narrative, which is moved along by a struggle for power between kings, satraps and, this being Gujarat, Jain mahajans.

The characters are all bound by caste identity and have no real agency. Rajputs are unthinking and eager to be martyred. Banias are scheming and cunning. Brahmins (my view is that Munshi created Mehta, though a Bania, in his own Brahmin image) are wise and so on. The suppleness and pragmatism that actually underpin Bania culture is missing from Munshi’s Banias, perhaps because as a Brahmin he doesn’t understand them.

Munshi’s male protagonists, the translators tell us, “are strong men, almost in the Nietzschean sense. He has no sympathy for weakness”. The less said about the women the better, and it is obvious to the reader that “Munshi believes that a woman achieves completion only when she finds a soulmate in a man”. Naipaul has written bitingly about Indian obliviousness to surroundings and the lack of observation (contrasting our writers to others like Flaubert and Maupassant and even Virgil). This novel would validate Naipaul’s thesis.

As the authors write: “Oddly enough, nowhere in the novel does one get a sense of Patan during that period. In fact, for a historical novel, there is a surprising scarcity of information that would paint a vivid picture of what Patan was like in the 12th-13th century and how its citizens might have appeared.” This is true. Munshi’s story can be placed anywhere at any period in India. The translation itself is smooth and easy, though for some reason certain words have been left untranslated. One can understand ‘daatan’ because ‘neem twig’ would sound awkward, especially when used in conversation. But how many readers would know what Jain upashray means? On the whole, however, this is a quibble. Those who wish to understand Gujaratis should consider buying this book, particularly for its first-rate introduction. For the rest, there isn’t much here of interest.