Keki N. Daruwalla belongs to a generation of poets who transformed Indian poetry in English into what it is at its best today: understated, terse, imagistic, free from excessive ornamentation, eloquent without being verbose. That does not mean the poets belonged to a ‘movement’ or wrote the same kind of poetry: on the contrary, poets like Nissim Ezekiel, Adil Jussawalla, Dom Moraes, Jayanta Mahapatra, A.K. Ramanujan, Arun Kolatkar, Eunice D’Souza, Kamala Das, Gopal Honnalgere and Keki Daruwalla himself were as different from one another as poets could ever be, in their perspective as well as idiom. Nissim Ezekiel, commenting on Daruwalla’s Under Orion (Writer’s Workshop, 1970), had observed, “Such a bitter scornful, satiric tone has never been heard before”. That tone made him say later that the poet “was born full-grown from the head of some hitherto unrecognised goddess of poetry”. Something of that bitterness still survives in Daruwalla’s poetry, but as Jeet Thayil observes in a note on him in 60 Poets (Penguin, 2008), “In later poems, he tempered his severity with a grudging acceptance of human frailty”.

Naishapur and Babylon, which takes its title from a verse from Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat in its Fitzgerald version (Whether at Naishapur or Babylon,/ Whether the cup with sweet or bitter run,/The wine of life keeps oozing drop by drop,/ The leaves of life keep falling one by one), testifies to Jeet’s observation of the gradual sobering of Daruwalla’s cynicism and even a new awareness of the darkening dusk—perhaps natural to poets like us growing older and lonelier—despite his poetry’s continuous, if ironic, engagement with personal and social histories with their violence and decay, its intimate and sympathetic observation and hearty celebration of nature and its unerring appeal to our auditory imagination. Anyone who has listened to his strangely dismissive and yet youthfully vigorous reading even once is incapable of forgetting that tone while reading his poems in silent solitude.

Arundhathi Subramaniam, to whom the collection has been dedicated, has a poetic and perceptive introduction that points to Daruwalla’s usual “canvas of panoramic vistas of mountain and steppe, giddy precipice and ocean, often Himalayan, Central Asian or Greek, viewed through the prism of historical imagination” and his “wooded”, “river-incised” landscape where “the winds are redolent with the scent of medieval voyages, of Egyptian antiquity and Aegean myth”. It is darker landscape now though with birds that are less predatory. The poems take us to Ladakh, where the red-robed monk slows down life “with mumbled prayer that slow-rolls the cylindrical prayer-drum” (What Lights Up...) to the “night-country”, where the goddess is driven under the earth by the long-bearded messiahs who thought she had a hotline to the “manufacturer of stars”, with the result that axe and saw mill work overtime in the groves which were sacred to her and the new generations are afraid of the revelation of “the grain-giver, barely goddess, goddess of word and melody” (In Night Country). The poet has always empathised with women, which he again proves in the poem Naropa’s Wife, about a Tibetan Buddhist saint who left his wife Ni-gu-ma (not unlike Gautama, who had left Yashodhara and Rahula) and went to Kashmir to pursue the saintly path. It is the wife who speaks in the poem. She had felt “the spasms of his coiled silences” even when he revelled in her body, and one day he went away from the ephemera, the illusion of materiality, telling the world women are but beguiling swamp and deception: He took the road/ I took the goat track to solitude./But my solitude was not ephemera (Naropa’s Wife).

But there are moments when the poet is fascinated by the sheer mystery of nature, lost in rain that soft-spears the earth and comes out with tuber-memory, still not losing sight of the winged world of magpie robins and spotted owls that wait for the rain to end (Rain), or in watching the black-necked cranes coming like a dark cloud from Tibet, sensing their kinship with the valley of compassion, Gangrey, where none is harmed (Cranes). A travel book on Tibet teaches the poet to shun straight lines and learn of wheels and circularity, so that he knows better the arc of his destiny, the wheel of existence that never moves in straight lines (A Travel Book on Tibet). Gandhi, “circling the jagged rim of a volcano”, too, knew this as he kept inviting death “walking into the knives of Noakhali and the blood-dripping lanes of Calcutta” (Gandhi). There are, too, meditations on winter, when time that discovers its element like a caesura at the end of a long musical note and stations itself at the centre of things and non-things, looks back while the landscape broods (Barbet). Tiresias, Creon, Orpheus, Oedipus, Persephone: you are in the world of myth—so close to the poet’s heart (art) in the section Orpheus and Persephone.

Luxor Diary takes us to Daruwalla’s familiar realms: Rameses III, who meets the gods as his equals, and even slides an arm around the waist of Isis, the goddess of magic and kindness and introduces his son to dog-headed Thoth, the gate-keeper god, and Ptah, the keeper of souls, and to Queen Hathshepsut, seeking henna and incense from the King of Punt. There are many more travel poems, poems on paintings, still lives, five moving poems for Anna Akhmatova, a poem on rereading Doctor Zhivago, beautifully lyrical poems on the river and on love, even some excellent translations of Faiz Ahmed Faiz that make us crave for more. Daruwalla proves once again that he is as much a recorder of the people’s past as of the pains of their present, summed up so well in Prayer on January 30, where he prays, “Let not the harsh winds of our times blow love away” and “Let the forest leaf. Let the lyric leaf”.

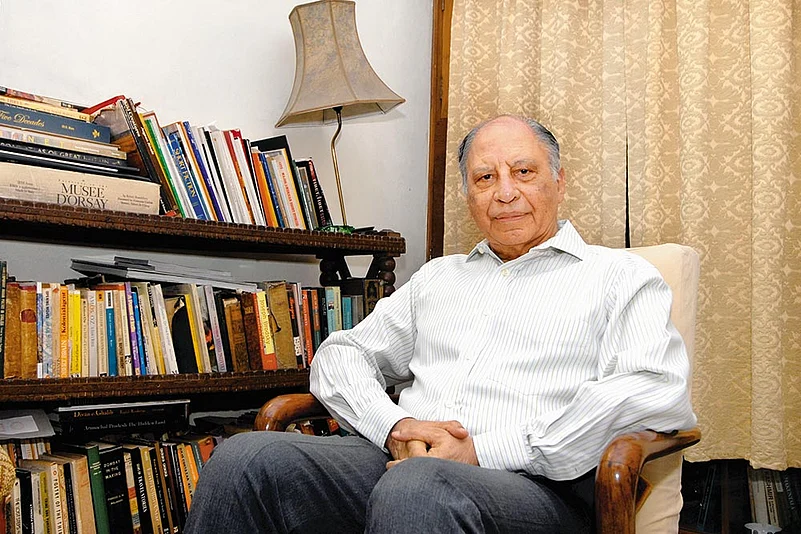

‘Tree bursting with apples’: the poet Ranjit Hoskote at a reading

Ranjit Hoskote, poet, editor and a well-known critic of art and culture, is easily one of the most sophisticated Indian poets of our time writing in English. The poems in Jonahwhale are, in one sense, akin to the tradition set by Daruwalla—though very different in setting, structure, style and thematic consistency—as they are centred on places and invokes mythical narratives, this time from the Holy Bible. But the playful poems form a cycle in three movements and connect the local with the cosmic and the present with our colonial past in strange and beautiful ways, like connecting Jonah, the legendary biblical prophet who escapes death after spending three days in a whale’s belly, and Captain Ahab of Melville’s Moby Dick, obsessed with the whale that had bitten off his leg. The poems remind us of our several pasts, recalls encounters with whales, as well as colonisers. They annotate huge chunks of global history and dramatise geography, still appealing to the contemporary urban reader with her angst and alienation—social as well as linguistic. Complex, dazzling, aware and precise, the poems carry us along the ocean, accompanied by the rhythm of the waves, whose legendary creatures and even plankton we see through a hole in the whale’s skin, so that our prophesies are not entirely surreal. The poems are organised in three groups or ‘movements’: Memoirs of the Jonahwhale, Poona Traffic Shots and Archipelago. The book begins invoking the evocative lines of Brihadaranyaka: the great fish glides through the river/ touching the near bank/ and the far/ the self swims the currents / of dream/ and waking. And the series begins with a dreamy sequence at Churchgate on what seems like a day after the world has ended when “a plaster Gandhi with sulphur-rimmed eyes” stops him and tells him he has missed the last and only train that was “safe for a man who’s left half his life behind”. The poem is replete with surreal images of sleek women with their hands caught in pools of light, wine gleaming in brittle flutes, the king of incomplete nights waking up in the Midnight Hotel in the middle of the novel he is writing, a tree branching into the clouds after having sucked up all the reality it had been watered with, drowned gardens where water strokes the poet’s crown of leaves.

Poems that follow, like The Map Seller, The Atlas of Lost Beliefs and Seven Islands are pitched between dream and reality. Ocean appears like a symbol of total destruction, of a deluge that washes away the roots of trees, towns and shaken hearts, the only remaining hope for mortals being the seeds hurled back by her breakers for the chroniclers. Ahab grows into a metaphor for global trade and exploitation, of revenge and enslavement of people, his curse carrying across docks, derricks and opium factories with the trader’s sovereign eye. The whole section reads like a new Odyssey encompassing global history. The marine passage brings up images from many eras, colours, murals, tree trunks, seaweed, gulls, powdered bones, occupied cities, the violet belly of the ocean, Noah, Jonah, trials, prayers, tides practising their roar and the sequence closes with the Highway Prayer that ends, Craft me into this totality/ that never closes.

Poona Traffic Shots is a sequence of ten poems, shadowy yet rendered real with Peshwas and typists and the litmus lotuses of Khadki. The last lines can well be applied to the whole sequence: Through hard words and praise,/ legends are erased and rephrased in the dark,/ they keep their secrets inviolate. Archipelago, the third movement, has fourteen poems, including one-liners like “Under the Tree of Tongues (the first line, which is also the title of the poem) /there is no healing” or “A stupa with the night sky trapped inside, growling” (Planetarium). The Poet’s Life, beginning with the lines, He married birdsong./ He sailed to the black island. He survived gunshots and ending with He glued the spout back on the broken chocolate teapot./ He opened the door to the deck and prayed the tree would burst with apples is a fitting conclusion to the whole collection.

(K. Satchidanandan is a Malayalam poet and a bilingual critic)