“In 1974 alone, over one-and-a-half million people died in Sheikh Mujib’s liberated Bangladesh. How big was that number? Five times the number of Bangladeshis killed by Pakistani forces during the entire period of the liberation war in 1971. No natural disaster had claimed so many lives since the beginning of our national calendar. No ruthless tribal landlord or Maharajah in our history had been the cause of so many deaths in the subcontinent. No religious clash, territorial disagreement, or deadly disease subjected our people to helplessly witness the untimely decline of such an astronomical number of lives.”

This passage appears not anywhere near the beginning of Neamat Imam’s The Black Coat, but well past halfway through this astounding 256-page novel.

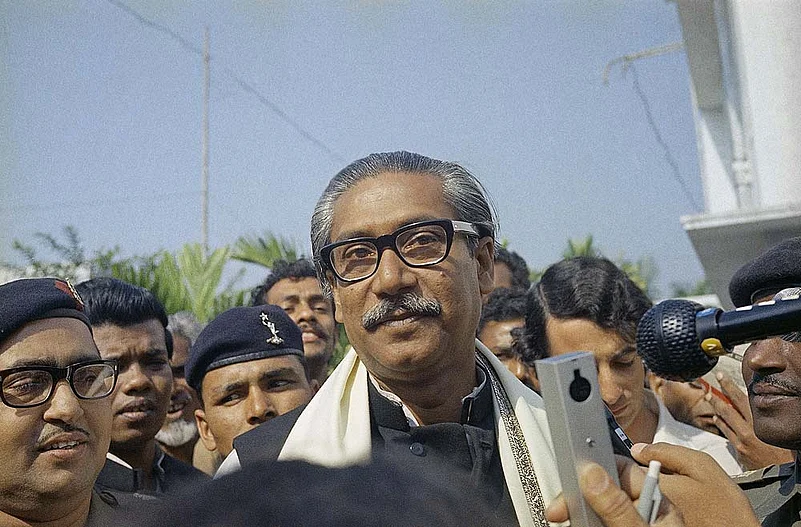

Imam, a Bangladeshi-Canadian writer-playwright, first came across An Unfashionable Tragedy, Australian journalist John Pilger’s documentary on the 1974 Bangladesh famine in 2005. In the film, he heard Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the father of the Bangladeshi nation, tell Pilger that around 27,000 people had died during the April-October 1974 famine. Imam began to look up different foreign sources and was shocked to find that the actual number was about one-and-a-half million. Which is when he decided to approach Sheikh Mujib as a contemporary Bangladeshi politician, one who “distorts information, lies, cheats and thinks irresponsibly”, bearing all the traits of a dictator.

It is exceedingly rare to find historical revisionism in the form of a fine work of fiction. And yet, that is what The Black Coat is, doubly remarkable that its aesthetic powers as a novel are not diminished but actually magnified by the strategic intention it comes loaded with. Imam opens the curtains with Khaleque Biswas, an idealistic journalist with The Freedom Fighter and reeking of self-righteousness, looking back at his life when like millions of other Bangladeshis just after ‘liberation’, he worshipped Sheikh Mujib. Quite unlike the person who lands up at his door in Dhaka from a remote village, Nur Hussain, “who knew nothing and understood nothing” about the 1971 war of liberation, Khaleque “knew what the war was about—its typology, its ambigiuous complexity.... What Sheikh Mujib’s six-point demands were...which song George Harrison sang at Madison Square Garden in New York in support of Bangladesh.”

As a favour, Khaleque is made responsible for finding Nur, a fifth grade drop-out, a job. This proves to be impossible. After telling himself that he hated the concept of “enslaving someone to secure my own comfort”, which would be “obvious exploitation”, Khaleque turns Nur into a ‘caretaker’ who cooks, sweeps, washes clothes, goes to the grocer, and looks after the house—essentially a servant—in exchange for regular meals, clothes and lodging because Nur “needed me”.

The pivotal moment comes one day when Khaleque is playing Mujib’s historic Dhaka speech of March 7, 1971, over and over again on his cassette player “to understand what Sheikh Mujib had in mind for me as an individual citizen”. A few days later, he finds Nur speaking parts from Mujib’s speech at a public place where they had gone walking. Nur literally plays back parts of Mujib’s speech by rote in front of slum-children, passing rickshawpullers, pedestrians and shopkeepers, rousing his audience “exactly as Sheikh Mujib had done”, with people in the crowd throwing coins at him saying, “Take this money, please.... Protect our motherland”. A business model is born.

To make the business of mimicry more professional, Nur is given a ‘Mujib’ hairstyle. The metamorphosis is complete when his Svengali gets Nur to put on Mujib’s trademark sleeveless black coat—the Black Coat of the title—thereby completing the ‘Mujib’ look. Before long, everyone is wearing the black coat to show their loyalty to Mujib by being Mujib. The irony is that the black coat not only makes Nur Hussain and others become Sheikh Mujib but it also makes Mujib the iconic Mujib: “Wearing that coat, he could easily stand beside Gandhi, Castro, Mao Tse Tung, or any other world leader of that stature”.

The chapter dealing with the meeting of Nur and Khaleque with Sheikh Mujib is deftly anti-climactic. When Mujib asks Nur whether he thinks a monument should be built at Nur’s hometown as a memorial to a 1971 martyr, the latter simply nods. “So be it”, Mujib responds. What Imam shows is Mujib talking to himself. The Black Coat is not just a truth-seeking historical tract in disguise. It is a novel about the idea of the simulacrum and doubles, about power crafted out of con jobs and pretence, about the theatre of politics.

The lie of the land takes on absurdist proportions when an Awami League MP tells Mujib, “Can you believe.... after only three years’ work we are only three years behind America?” He tells him that Bangladesh would in twenty years have at least half a dozen Nobel laureates in “science, medicine and poverty alleviation”, adding the possibility of a “transcontinental competition with Lichtenstein in the field of investment and banking”, a country he describes as “the largest country in Europe, Mujib Bhai, larger than France and Germany”.

Imam writes in a deadpan style that is remarkable in its ability to capture hysteria. Shot through this extraordinary book are strange scenes depicting the famine-ravaged and the refugees, not in the heartstrings-tugging way most reimagined historical tragedies are presented but almost matter-of-factly, thus magnifying their tragedy. The cartoon adventures of the Goopy Gyne-Bagha Byne-meets-Victor Frankenstein and his Monster duo constantly collide with the Grand Guignol of the Sheikh Mujib years. Out of this concoction of the darkly comic and the Technicolored tragic, only one of our two protagonists comes out unscathed.

Very few novels examine a period in history so convincingly even as it turns away from the standard style of historical fiction. Imam does this in this hyper-realistic tale of fools, thugs, dangerous idealism and sanctified pretence, reminding us who have forgotten a secret function of the novel: to unsettle us, instead of just be moving.

(Indrajit Hazra is the author of The Bioscope Man)