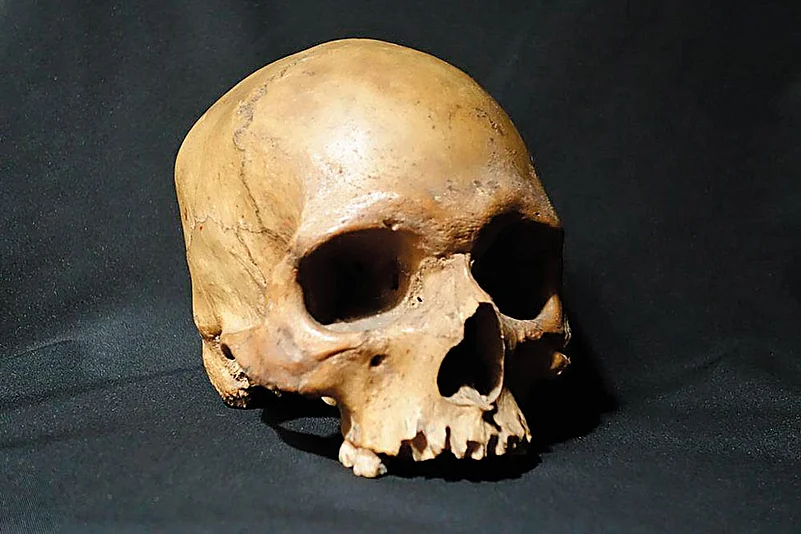

It may not have caught the attention of historian Kim Wagner had there not been a neatly folded slip of paper in the eye-socket of the skull, which read: “Skull of Havildar Alum Bheg 46th Bengal Infantry, who was blown away from a gun. He was a principal leader of the mutiny of 1857 and of a most ruffianly disposition.” Intrigued by the manner of execution and the subsequent collection of the skull as a trophy, Wagner sought to restore some peace for the dispossessed by piecing together the history of barbaric treatment of the natives. It is a work which scholars call subaltern prosopography, depicting the cruelty of the natives and the barbaric retribution which followed.

Following the execution, the skull was carried home by Captain A.R.G. Costello, a witness to the execution in Sialkot on July 10, 1858, before it resurfaced a century later at pub The Lord Clyde in 1963. It took another 50 years before the inglorious skull coincidentally reached a Danish historian researching imperial executions. The Skull of Alum Bheg is a meticulously researched, gripping narrative that brings to life the human aspects of imperialism. Staying clear of both mindless empire-bashing and jingoistic empire-nostalgia, the narrative provides a nuanced understanding of the past by portraying the personalities on all sides of the conflict. The brutal outcome reflects the relationships and circumstances between the ruler and the ruled, leading us to address the enduring legacies of imperialism that are still with us.

Resentment was brewing following the Barrackpore mutiny, in which hundreds of native sepoys were slaughtered in 1824, with the soldiers increasingly getting convinced that their officers were deliberately, and insidiously, undermining their ritual purity. The British did little to assuage doubts and fears attached to biting the cow or pig-fat greased cartridges. Instead, by disbanding the sepoys of first the Barrackpore and later the Berhampore garrisons they only managed to stoke resentment amongst their most trusted and most needed support to rule 200 million people. The native foot soldiers outnumbered their counterparts; there were five native sepoys for each British soldier. Relying on numerical strength, the natives mutinied against their racist and rapacious rulers.

Wading through reams of historical records, Wagner weaves together a compelling history of the mutiny as it spread across the northern areas. In some ways, the popular uprising was an armed rebellion against a longstanding climate of dissatisfaction, brewing out of perceived religious subjugation, which had played out differently across regions. The Sialkot cantonment was on the tenterhooks of an uneasy calm, partly because the sepoys of the Bengal Army constituted a uniquely coherent group who found a sense of unity as they lived far away from their villages in Awadh. But they could not be insulated from the disturbing news of mutiny for long, and in the ensuing chaos personal animosity had merged with general discontent to claim innocent lives.

Shockingly, however, the existing evidence makes no mention of Alum Bheg as the principal mutineer at Sialkot, for which he was held guilty. Neither is there any indication that he played any role in the brutal assault and killing of Jane Hunter, her two-year old son, and Dr Graham. Caught between the devil and the deep sea, Alum Bheg and his men chose to head for Delhi to offer their allegiance to Bahadur Shah. It was to be their undoing, as they were waylaid at Trimmu Ghat on the river Ravi in Gurdaspur, and were forced to flee into Kashmir. The British hunted them down, and the severity of retribution for this act of ‘betrayal’ was implicitly justified.

Wagner uses the story of one man’s death to excavate the weak underbelly of the 19th century colonials, who considered the outbreak of mutiny as personal attacks on themselves. As an act of retributive logic to the Kanpur killings, wherein slaughtered European women and children were dumped in a well, the British felt an unmistakable sense of achievement by consigning mutineers to a well in Ajnala. Wagner notes with dismay that there are no heroes in the book, only victims. Convinced that the execution of Alum Bheg was a deliberate attempt to deny him his funeral rites, the author proposes the peaceful site of the Battle of Trimmu Ghat, on the island in the Ravi, as his permanent resting place. Meticulously researched and vividly written, it is a page-turning narrative that lays bare Victorians’ macabre fetish for collecting body parts. But, cautions Wagner, the complexities of the past must be viewed beyond the moral binary of ‘good’ or ‘bad’.