‘Words are easy like a wind, faithful friends are hard to find,’ says Shakespeare. In literature, we keep seeing friends everywhere, and faithful friends are not that hard to find. But excepting a well-known few, the rest remain in the mist of our memory, reluctant to come to the fore. I’m reminded of a story about Mirza Ghalib. He had a very close friend with whom he shared many things—except mangoes. The friend did not care for mangoes. One day, he was seated in the veranda of Ghalib’s house, and Ghalib was there as well. A driver drove his donkey-pulled cart through the lane. Some mango peels were lying there; the donkey took a sniff but left them. The friend said, “Look—even the donkey [gadhā bhī] doesn’t eat mangoes!” Ghalib said, “Exactly, a donkey doesn’t eat it.” This story, apart from being a fine example of Ghalib’s biting wit, says one more thing—only with close friends could one take such liberties. The funny thing was that I couldn’t remember the friend’s name. I had to search online for long before I could find it—Hakim Razi ud-Din Khan. There are several such people lurking in the pages of literature.

Human civilisation’s perennial and greatest contradictions are war and friendship, but they both have contributed to its progress. If it has been war that has impelled human beings to invent new things, it has been friendship that has made them seek new pastures. Science and technology thrive on war and friendship. At least thus far, every civilisational advance has these two as unmistakable markers. No wonder then that our literature and history celebrate both. War is thunder and lightning and easily identifiable. In contrast, friendship is subterranean and quiet, and thus easy to miss. That is why we incessantly speak about wars of yore, but hardly about ancient friendships.

But friends are everywhere, just as God is to the believer. There is a Tamil usage that aptly describes this belief—thondra thunaivan—the one who never appears before you but is always with you. In Hindi too, there are several words to denote friendship. Ali and Fratt, in their essay on the history of friendship in India, say: “…(F)riendship has a rich vocabulary in Indian languages. The variety of words in modern Hindi alone, which can be translated as ‘friend’ (yaar, dost, saheli, saathi, sahayak, bandhu, jaani, ukht, mitr, hamdard, hamdam, habib, sahyogi, akka, sanghrakshak, wali, bhai, jigari, rafiq, sajjan, sakhi, aziz, nadim, hamsafar, to name only the most common) is vast. These words, which derive from both Sanskritic and Persianate roots, suggest that concepts of friendship were diverse and far-ranging in ‘traditional’ Indian society.

The Rig Veda says Agni, the God of Fire, is a friend who never hesitates to do what is in our best interest. Soma, the God of Drink, is a watchful protector who sees to it that we never come to harm. In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna requests the Lord to forgive him as a friend would readily forgive his friend—sakheva sakhyuh.

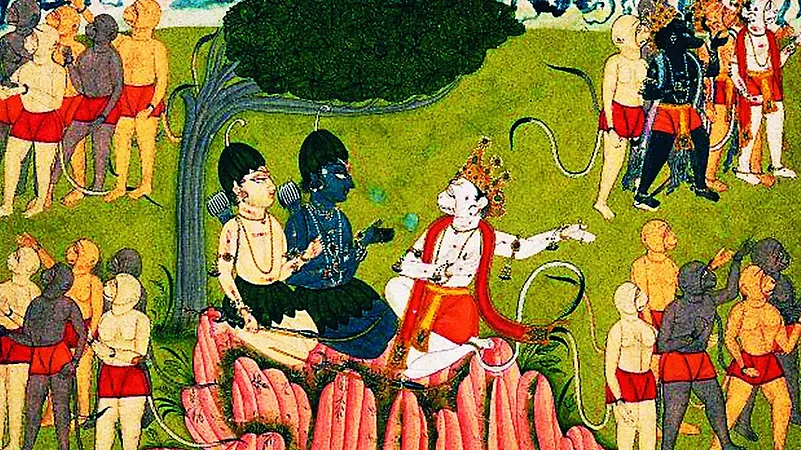

In the Valmiki Ramayana, Trijata, a dreadful-looking (ghora darshna) rakshasi, strikes a friendship with the beauteous Sita and consoles her on two different occasions when Sita is distraught. The Ramayana story has several such friendships. Kamban’s Rama says, “My father gave me the forest and now he glows because he has gained a few sons”. Rama considers his friends—Guha, Sugriva and Vibhishana—as sons of Dasaratha. Likewise, the Mahabharata has countless stories of friendships, the most glorious being that between Karna and Duryodhana. Panchatantra’s fables are collected in five parts, the first two parts of which are about friendship” “Mitra bheda (Losing Friends)” and “Mitra labha (Winning Friends).

Tamil literature, too, has many references to friendship. The famous Tiruppavai of the poet Andal is a celebration of camaraderie. She says, “kudiyirundu kulirnderol empavai”, which roughly translates to “Let us all gather and chill out”. Sangam literature is full of poets who don’t hesitate to chastise their king-friends who have turned rogue, or praise those who have acted honourably. My favourites are stories about two poets and their unusual friendships.

The first is a charmingly embellished account of friendship between Kopperuncholan and Pisiranthaiyar. Kopperuncholan, a ruler sometime in the second century CE, was a patron of many poets. But the one whose poetry he loved most was of Pisiranthaiyar. The king had known him only through his poems, as the poet lived in a distant town in the Pandya kingdom. The poet too knew about the king’s abundant love for good poetry. They kept exchanging notes, each promising the other that they should meet one day. Unfortunately, Kopperuncholan entered into a dispute with his sons who were in a hurry to take over the kingdom. Unwilling to confront them in battlefield, the king decided to take his own life by fasting. He sat facing north, and began to starve. Secretly, he was sure his friend would visit him and, driven by grief, end his life. When Pisiranthaiyar heard of Kopperuncholan’s fast, he rushed to the Chola kingdom to be at his friend’s side, but arrived too late. Then, exactly as Kopperuncholan had expected, Pisiranthaiyar ended his life in grief.

The second story is about the friendship between the poet Avvaiyar, a venerable old lady, and Adiyaman, a minor king who was in constant quarrel with neighbouring kingdoms. The story goes as follows: The king gets a rare amla which is supposed to make whoever eats it almost immortal. The king doesn’t eat the fruit. He calls his friend Avvaiyar and gives it to her, saying, “If you live long, it will greatly benefit both the Tamil language and the Tamil people.” Avvaiyar celebrates this in a poem, in which she says Adiyaman too will live as long as Neelakantha (Lord Siva). He didn’t, but that is another story.

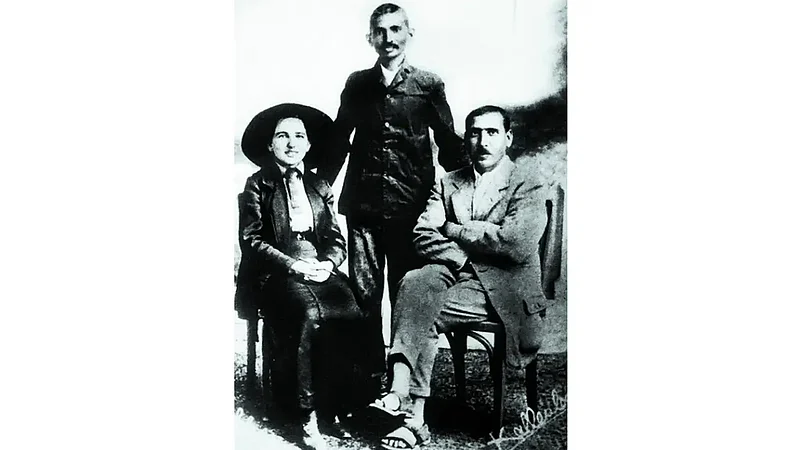

As usual, Mohandas Gandhi had distilled the essence of friendship perfectly, when he wrote of his close friend Herman Kallenbach. He said the memory of a friendship became a treasure, as it enabled us to translate into our lives the best part of the friend. This is true even with friendships we read about. They reside in you as memories, and make you a better human being.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Yaarana")

ALSO READ: Bonds And Verses: A Circle Of Urdu Poets

(Views expressed are personal)

P.A. Krishnan is an author in english and tamil