After a long wait of two years, the Complete Rolling Stone Interview of Susan Sontag is finally out in India, and everyone is talking about it! The twelve-hour long interview, taken over multiple sessions, is now a book-length conversation that is a delight to read.

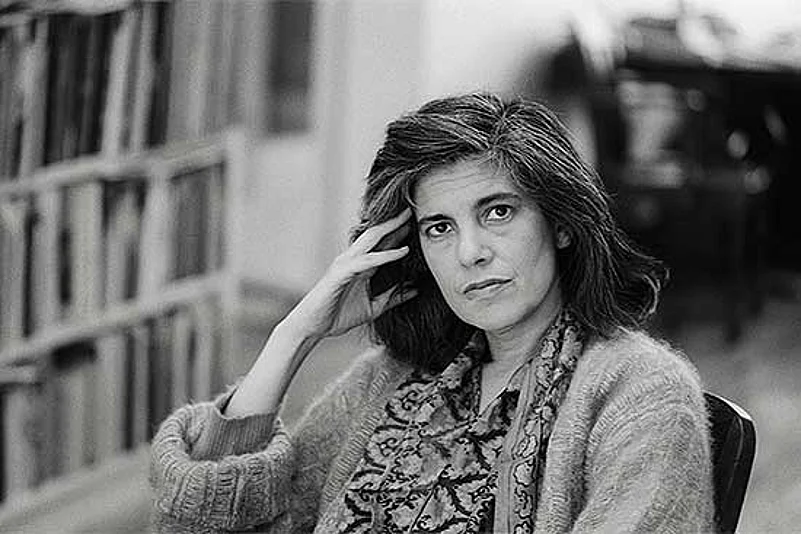

Susan Sontag is so much more than just an academic; she did nearly everything from writing novels to directing a play in war-torn Sarajevo. She reported from Hanoi. She published short stories and monographs on topics as diverse as photography, fascism and art. She was interested in pop culture at a time when academics were insulated from it. For over two decades, she was also a human rights activist, and at one point served as the president of PEN America. In fact, Sontag the person is barely reachable behind the towering myth.

It is then all the more arresting that the best thing about the Rolling Stone interview is not Sontag herself, but Jonathan Cott, the interviewer. Very alert to the fact that Susan Sontag's fame and her larger-than-life persona as a filmmaker, novelist and activist created its unique problems, including her seemingly endless appetite for talking about herself, Cott provides well-timed resistance, disagreement and occasionally the nudge in the right direction. And that's what makes it so readable.

Jonathan Cott and Susan Sontag met when he was studying at Columbia as an undergraduate and she was teaching there. In the book, those years of her life come up more than once, and at one point she casually mentions how she no longer needed to look up references because she had been teaching things like Homer's Iliad semester after semester for years. This withering ease around difficult names in literature is another thing that marks her interview. At one point, she declares that she started reading at the age of three, and had read some world classics by the age of six: endearing, yes, but it is a bit hard to get past the boasting!

Although Cott is extremely good at trimming the excess, there is nevertheless a certain degree of hero-worship that runs through the book, though this by no means reduces its value. If anything, it makes it more human, if you remember that Cott is after all talking to a teacher, and an extremely charismatic one at that.

The interview meanders through many different topics. At one point, Cott asks Sontag, "Would you say that there is such a thing as a fascist sensibility?" Her answer is perhaps more relevant than ever in the currently volatile climate in politics everywhere. She refuses to see fascism as a property of any particular politics. Even the New Left, she contends, has shown a fascist sensibility, although she is very quick to point out that this does not make it fascist. "There are contradictory impulses in everything," and the way to guard against fascism is to look for those contradictions and "to purify them".

A more light-hearted moment occurs when the interviewers asks about love and sex. Is it possible to be with someone who does not share your interests? With typical wit, she laughs about "that famous problem of breakfast". What do you do the next morning when you are having breakfast and you have nothing to talk about? But she elaborates her wariness with the expectation around romantic love at another point: 'We ask everything of love. We ask it to be anarchic. We ask it to be the glue that holds the family life together, that allows society to be orderly and allows all kinds of material processes to be transmitted from one generation to another.'

At one point the interviewer asks if Sontag's identity as a woman determines her writing in any way. In her reply, the maverick theorist shows her true form: she talks about black writing, French feminism, ghettoization and many other things; finally she says, 'I don't think that has anything to do with my being a woman — it has to do with me, and one of the things about me is that I am a woman.' In the course of the interview she talks about her other identities too: mother, wife, child, writer and above all, a reader.

She confesses to reading up to one book a day, and when asked what reading means to her, she says, 'Reading is my entertainment, my distraction, my consolation, my little suicide. If I can't stand the world I just curl up with a book, and it's like a little spaceship that takes me away from everything.'

And yet, this escapism fades when you think of her last book: Regarding the Pain of Others. There she talks about empathy, wars and the need to stay attentive to the plight of others. The Susan Sontag of that book is very different from the person who gives the interview to Rolling Stone. Perhaps the only way to explain it is to go back to her own words right at the very end of the interview: 'the most awful thing would be to feel that I'd agree with the things I've already said and written — that is what would make me most uncomfortable because that would mean that I had stopped thinking.'