The exhibition, divided into six sections, covers just about every aspect and type of manuscripts. One section elaborates on the wide range of substances used: the bhurja patra or the birch bark, the tada patra (palm leaf) and the sanch pat (aloe leaf). Paper came in with the arrival of Islam. Then there were bamboo, ivory, clay, copper and other metals, and even textiles which became the canvas for the scribes. One exhibit shows Kali mantras beautifully embroidered on a piece of cloth with auspicious lotus and feet motifs. "In the West, writing happened only on parchment or handmade paper. The variety of material used in India is unparalleled in the world," says Gopalakrishnan.

Another section entitled Making of the Manuscript shows the instruments of writing: the humble shalakas (pens), pen knives with sumptuous motifs, a wooden manuscript box with lacquer sheen finish, ornate book stands, pen stand, pencases and ink wells. There is a 20th century brass ink well with an expanded kalasha-like base and cap like the shikhara with loops on the side for holding the writing instruments. Another highlight of this section is the cover of a Jain manuscript illustrating the 14 dreams of Queen Trishala when she conceived Lord Mahavira. The panels show the subject of each of these dreams: elephant, bull, lion, Laxmi, garland, full moon, bright sun, flag, vase, lake, ocean, celestial chariot, jewel basket and smokeless fire. Then there's the Vyasa Pith, the ceremonial stand that holds the manuscripts while the priests recite them.

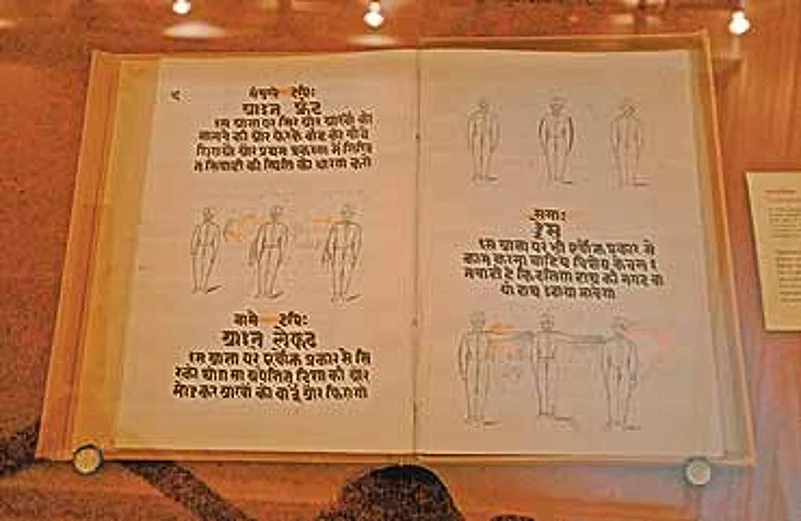

Padatishiksha, the infantry manual of Ranbir Singh

The manuscripts range from humble texts to spectacularly illustrated ones. In format, they range from horizontal pothis to tiny scrolls. They also reveal the evolution and spread of our knowledge systems. "There are works from every sphere—cosmology to cosmetology," says Gopalakrishnan. There are ancient texts on architecture, music, philosophy, medicine, even dream interpretation and veterinary science, like the Gajayurveda, the study of elephants, illustrated in the Mewar miniature style. Padatishiksha is a 19th century infantry manual of Raja Ranbir Singh.

Also on display is the priceless Gilgit manuscript, the oldest in India. Discovered by shepherds in Kashmir in 1931, many of these bundles haven't been deciphered yet. It is one of the two Indian nominees being considered for UNESCO's Memory of the World Register, on seminal texts of the world. The other entry is Rigveda from the Bhandarkar Research Centre, Pune. The show also has a wonderful copper tablet inscribed with the prayer of prosperity for five castes: blacksmiths, carpenters, potters, weavers and goldsmiths. The obverse side illustrates each of these professions right down to their tools. Subika, a manuscript on portents and divination from Manipur, is accordion-like, with 23 intricate folds.

Razmnama, the Persian Mahabharata

The exhibition shows that manuscripts have also been objects of worship in India. The Guru Granth Sahib, for instance, is regarded as an embodiment of the Guru. In the Namghar Vaishnava monastery in Majuli, Assam, it's the Bhagwad Purana that's read and worshipped by the priests. The damaged texts are known to be 'cremated' or ceremonially immersed into the river by people.

The show also highlights remarkable cross-cultural influences. A 19th century Burmese copper plate shows India-inspired figures and foliage motifs brought to life with lacquer paints. The common colonial heritage of the two countries is presumed to be the reason for this exchange. The most striking object is the Razmnama, the Persian translation of the Mahabharata by Abul Fazl. It was done at the initiative of Emperor Akbar who is reported to have started the tradition of translating religious texts to promote better understanding between various religions.