“And how does it feel?” said Mr Singh, the short, plump man who had shown me into my room at the hotel. I said, “It’s a lot like Lahore.” But that was only partly true. The way the leaves of trees hung above the roads of Delhi, obscuring the sky, and the meringue-like buildings on Connaught Place—these were like bits of Lahore. But there had also been temples on the way from the airport, and signboards that gave the names of streets in three different scripts. A woman was standing at the hotel entrance in a blue-and-red uniform, which was like the uniform worn by Lahore’s recently inducted female traffic wardens, but most of them had been quickly chased away by whistling car-drivers.

“There are some differences,” I said to Mr Singh. “But there are similarities too.”

And Mr Singh tilted his head, closed his eyes and smiled with all his gums, as though the question had been answered to his satisfaction.

I was taken that night to meet a distinguished old writer, a man who had lived once in Lahore. Even now, more than 60 years after he had fled the Partition violence, he spoke of his city as though he had just left it behind: he recited lines from Faiz and Faraz, described the tempestuous Amrita Sher-gil and named his many friends and colleagues, most of whom were dead.

I said, “Can the borders be undone?”

He looked into his lap and frowned. “No,” he said. “They mustn’t be undone. Aana jaana ho. But the lines must stay.”

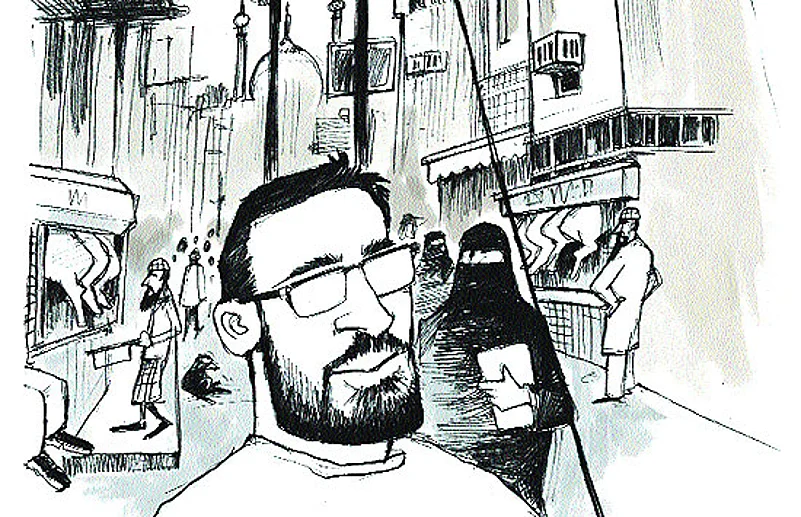

Afterwards we drove to a restaurant near the Jama Masjid. The world changed: the well-lit mansions and boutiques became black apartment windows and narrow, unshuttered shops; the roads became gutted alleys. Men and boys wore white skullcaps here, and some of the women were in burqas. The skinned torsos of animals were hanging everywhere from strings.

“Muslim area,” said the girl sitting next to me in the car.

Two days later, I saw an odd spaghetti script on the signboards at Bangalore airport.

“It’s the local language,” said Sai, a large, raspy journalist who came to interview me at the hotel in the afternoon. “Do you know what it’s called?”

I thought about it and said, “Kannada.”

Sai was impressed. “And what are the other South Indian languages?” He leaned back in his chair and folded his arms imperiously.

“Malayalam,” I said. “And Tamil. And Telugu.”

“Well done,” said Sai. “Well done.”

He was a lover of music. For more than 10 years, he had been collecting rare recordings of Indian and Pakistani singers.

“I lived with Abida in her house,” he said casually.

“What’s she like?” I said, having seen the face-making, hand-waving singer only once at a concert in Lahore.

“Oh she’s normal,” said Sai. “And she’s a darling. She’s a total darling.”

It was time to have my pictures taken. The photographer, a boy called Khan, took out a black jacket from his backpack and handed it to me.

I tried it on. It was exactly my size.

“Ek dum badiya,” said the photographer, now circling with his camera.

And the word badiya, no longer used in my Lahore, was one I immediately recalled from a childhood fed by Hindi films, which came to us in pirated videotapes and were played on rented VCRs on weekends.

* * *

“From what you are saying,” said the man in the glasses, “there is no difference between India and Pakistan. But then why this tension is there?”

The reading, my last, had ended, and the man in the glasses had stayed on in the conference room of the Habitat Centre in Delhi. I was standing at the podium and signing some books, giving the man a long, complicated answer about states and ideologies, democracies and dictatorships, the damage done by Cold War strategies and the benefits of being in the Non-Aligned Movement. But my mind was somewhere else: I was thinking of the view I had from the window of a Mumbai apartment, where I’d gone some nights ago to attend a book party. It looked onto a wide marsh that began to glitter as the light faded away. On the far edge of the view, forming a kind of border region, was a curving scrap of tents and huts.

“Slums,” said the girl sitting on the floor of the apartment and drinking red wine from a beautiful oversized glass.

“Like Slumdog Millionaire,” I said, only half-jokingly.

But she said, “Yup. Mostly Muslims.”

Muslims in Mumbai: they had become real to me on my last night in Bangalore. I was sitting in an autorickshaw with Sai and Khan and was going, after eating my first dosa in a crowded street, to have a special kind of chai at a place called the Makkah Cafe. On the way, Khan’s mobile phone rang. It was his mother. She was calling from their home in Mumbai.

“Badiya,” said Khan.

And now he was holding out the phone for me to take.

I pressed it to my ear and said, “Salaamaleikum.”

“Waleikumassalam,” she said.

“Your son and his friend are taking me around,” I said. “We are having a very good time.”

The autorickshaw roared and turned a corner.

“Mashallah,” she said.

“How are you?”

“Allah ka fazal hai.”

“You must come to Pakistan.”

And she said, “Inshallah.”

So now, to the man in the glasses, I said, “People everywhere are the same. Or people everywhere should have the same rights. At least that’s my view.”

And the man smiled, took his signed copy of the book and went away.

But my last night in India was marred by a fever: I had cut my toe in three places the previous week and had not worn a bandage, and by 10 at night, my foot was swollen, my body hot and shivering in the large hotel bed.

I called the reception desk downstairs.

And they promised to send for the doctor.

He came with his briefcase and was led in by a worried-looking Mr Singh. The doctor held up my toe, dabbed it with cotton wool, covered it with a cold white ointment and wrapped it in bandage.

“You will be taking antibiotics,” he said and began to write out the prescription on a notepad.

“Thank you,” I said, and was still amazed, because I hadn’t expected a doctor at this time of the night, not in a country so close to mine, where no doctors ever came to look at the bleeding toes of hotel guests.

“Your name?” said the doctor.

“Ali Sethi.”

“Anil Sethi?’

“Ali Sethi. A L I.”

“Oh,” said the doctor, and looked up inquiringly from his notepad. “Half Indian and half... Muslim.”

(The Lahore-based writer was recently in India to promote his first novel, The Wish Maker.)