David Gilmour disclaims any intention of exploring empire as a political institution or of assessing its benevolence or oppression. This is a social history, brimming with human interest and anecdote; but its magisterial scope and depth make it a valuable contribution to the debate about imperialism.

Gilmour’s previous book on the Raj was a definitive portrait of the Indian Civil Service, dubbed “heaven-born” for their brilliance and incorruptibility. Individual ICS officers figure in this book too; but the author resists the temptation to generalise about their motives. Rejecting the ideological stereotyping by anti-Orientalists like Edward Said, Gilmour works outwards from his research into personal letters and diaries, memoirs and official reports, which he rightly regards as the foundations of historical insight.

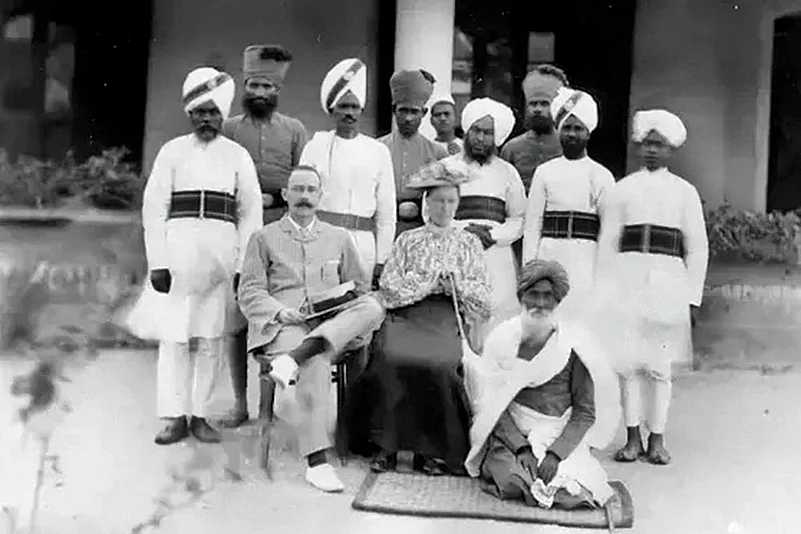

His panoramic cast of characters ranges across grand viceroys and randy subalterns, conscientious judges and district officers, memsahibs and prostitutes, racist planters and pig-sticking cavalry officers. Their lives, motives and attitudes to ‘natives’ vary enormously. And yet, certain common traits emerge, most of all a determination and stoicism that don’t belie the proverbial British stiff upper lip.

The novelist Paul Scott noted that India had become an essential, if often unconscious, element of British identity, a cosmopolitan sense of global entitlement that could infuse the most suburban English surroundings. For many who undertook the arduous sea journey, India offered adventure, opportunity and riches; but it also required courage and fortitude. The British in 17th century Bombay had a saying: “two monsoons are the age of man”. A century later, it was estimated that half the Britons who went to India survived less than five years.

Life often was lonely, uncertain and uncomfortable, especially for thousands of district officers and their wives, judges and policemen, doctors and civil engineers who were stationed in the mofussil, and often in the most inhospitable forests or mountainous regions. Some coped by keeping aloof from Indians, congregating in exclusive clubs, maintaining archaic conventions such as dressing for dinner and whiling away their leisure in orgies of animal-killing. Almost all felt a strong sense of duty, and most were motivated by a desire to improve the lives of Indians.

For us in the 21st century, it’s hard to imagine the job satisfaction of a medical officer who had persuaded a whole district to undergo inoculation against small pox or an engineer who had built a canal irrigating the land of thousands of peasants or a district magistrate who had peacefully resolved a blood feud. Nor can we doubt the genuine commitment, confirmed by private letters and diaries, of imperial policy-makers promoting liberal values and tackling social evils like female infanticide, widow-burning, child marriage and caste oppression. Gilmour constantly reminds us that individual motives could be very complex and that the same person might be selfish or altruistic in different circumstances.

This book dispels some negative stereotypes peddled by the Said school of anti-Orientalism. The memsahib, so widely blamed for ending male British attachment to Indian bibis, was herself the victim of crippling loneliness, outnumbered 7,000 to one. “It is not surprising,” writes Gilmour, “that they sometimes felt lonely, scared, beleaguered—and rather cross.” Nevertheless, it was British women, led by an enlightened vicereine, Lady Dufferin, who established the National Association for Supplying Female Medical Aid to Indian Women in 1885, recognising the needs of women in purdah and treating four million Indian women by 1914.

Although the ICS was recruited predominantly from the British middle class, by the 1930s half the service had been Indianised, while the remainder included socialist, even communist sympathisers. The average district officer spent most of his time on horseback touring his district, camping in the open and dispensing justice. “I knew that the world was on my shoulders,” wrote one, “and for just this reason my heart was light.” Far from siding with their own race, the ICS was constantly at loggerheads with the British plantocracy over the latter’s mistreatment of Indian labourers and peasants.

Most British officers of the Indian Army spoke the language of the regiment, knew every man in their unit and gave them paternal advice. Gilmour concludes that the stereotyping of Britons in India by Said and his followers is “fundamentally anti-historical, judging the past from the zeitgeist and morality of the present”, and ignores “complexity of motive”.

Perhaps the best example of mixed colonial motives was the ‘Clinical Christianity’ of the missionaries, who by 1936 had established 200 Indian hospitals, employing several hundred European and American doctors, many more Indian doctors and 2,000 nurses.